Ribera: Was this the vision of a sadist?

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, NaplesAccording to some, Jusepe de Ribera enjoyed painting torture. A new exhibition seeks to challenge that view of the 17th-Century artist, writes Kelly Grovier.

No artist has ever managed to put the pain in painting quite like the 17th-Century Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera, whose macabre canvases of flayed flesh and unflinching drawings of executions are the focus of a gritty new exhibition in South London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery, Ribera: Art of Violence. For Ribera, the brutal suffering (real or imagined) of everyone from early Christian martyrs to mythological satyrs was more than merely a recurring subject. Torture was his favourite colour.

More like this:

Attempting to capture the ferocious essence of Ribera’s vision, the 19th-Century French poet and art critic Théophile Gautier described the Baroque painter’s legacy as representing a “slaughtering school of painting, which seems to have been invented by some hangman’s assistant for the amusement of cannibals”.

Ribera may never have dabbled in cannibalism, but his reputation is not so easily scrubbed clean of persistent rumours of barbaric behaviour by historians convinced that only a hands-on approach to cruelty could explain the shocking authenticity of his work.

Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

Museo de Bellas Artes de BilbaoBorn near Valencia, Spain, in 1591, Ribera migrated in his early 20s to Rome where he acquired a disarming nickname, ‘Lo Spagnoletto’ (or ‘the Little Spaniard’), and honed his skills in the arts of drawing, painting, and racking up dangerous debts. Fleeing impatient creditors, Ribera ran south in 1616 to Naples, then under Spanish rule, and there found himself a wife and a network of wealthy patrons eager to his distinctive blend of breath-taking realism, melodramatic shadowing à la Caravaggio, and ghastly subject matter.

Flesh and blood

It has long been whispered that Ribera made sure that competition for commissions in Naples was kept to a minimum not merely by perfecting his craft (using live models to capture every flex and flinch of tormented human muscle), but by bullying and perhaps even killing rivals. The organisers of Ribera: Art of Violence are quick to push back against historic accusations that he was ever engaged in mafioso-like efforts to intimidate his peers or that he had anything to do with the untimely death by poisoning of the Bolognese painter Domenichino – a charge that has dogged Ribera for centuries.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum“Ribera did not necessarily have to be a sadist,” insists Edward Payne, co-curator of the exhibition, “in order to produce his images of violence, and an artist’s painterly or graphic production is not necessarily indicative of his personality.”

Whether or not Ribera conspired with his contemporaries Belisario Corenzio and Giovanni Battista Caracciolo (alleged partners in the so-called ‘Naples Cabal’), as has long been maintained by scholars, his gruesome imagination – memorialised in a bloody trail of torture scenes – is one of art history’s darkest alleys.

Ribera: Art of Violence invites visitors down that grisly age. The exhibition opens with a morbid meditation on the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, who was flayed alive and then beheaded for his steadfast faith. Gallery goers will be greeted by a range of depictions of the torture of the apostle that have been borrowed from collections in Florence, Barcelona, and New York. A relatively early oil on canvas devoted to the subject (from 1628) finds Ribera in a moment of uncharacteristic restraint, content with envisioning the anguishing seconds just before the hideous torture commences. The saint’s eerily luminous flesh is still unsevered in the centre of the work, as a blade is sharpened in the margins by a knifeman whose face is half swallowed by shadow.

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya/Calveras/Mérida/Sagristà

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya/Calveras/Mérida/SagristàBy contrast, a later canvas from 1644 sees the artist going all in on explicit barbarity. Here, a snickering executioner slowly slivers the skin off Bartholomew’s forearm with the slavering relish of a peckish carnivore slicing strips of serrano ham.

In order to peel back the layers of Ribera’s imagination, the show has been organised into thematic sections designed to help visitors dissect the artist’s achievement. To substantiate the show’s broader claim that the painter has been somewhat unfairly singled out by posterity as a savant of savagery, a range of contextual source material has been gathered that demonstrates the contemporaneity of his violent vision. For a section of the exhibition entitled ‘Crime and Punishment’, handwritten criminal proceedings that chronicle the dreadful punishments to which convicts were sentenced – from floggings to burning at the stake – illustrate how widespread the consciousness of callousness was in Ribera’s day.

A selection of graphic plates from the French printmaker Jacques Callot’s Les misères et les malheurs de la guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War), published in Paris in 1633 – now showing a mass hanging, now the etched flames of an immolation – is intended further to corroborate the culture of coarseness in which Ribera’s imagination emerged.

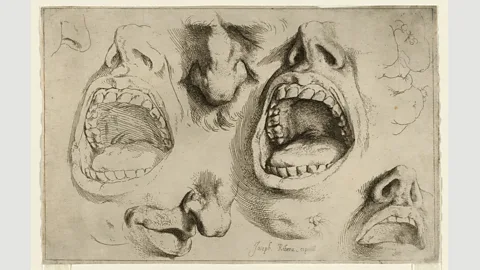

A display devoted to ‘Skin and the Five Senses’ explores, through a series of unsettling studies, Ribera’s fascination with flesh and his agility as a draughtsman of distressed human anatomy. Among the more haunting of the works assembled here is a riddling red-chalk drawing from the early 1620s entitled A Bat and Two Ears. The painstakingly detailed image depicts a grinning bat that grips in its talons a Latin scroll that reads ‘Virtue shines forever’ as it swoops towards us above a floating pair of disembodied left ears.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/ Scala, Florence

The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/ Scala, FlorenceThough the curators note – in the show’s eloquent accompanying catalogue – that the bat is a conventional emblem for the artist’s native region of Valencia (owing to a legend that one landed on the helmet of King James I of Aragon while he fought to recapture the territory in the 13th Century), no adequate interpretation of the drawing definitively decodes its inscrutable symbolism. In attempting to navigate the ambiguous gloom of Ribera’s dark art, our taunted senses flap about blindly.

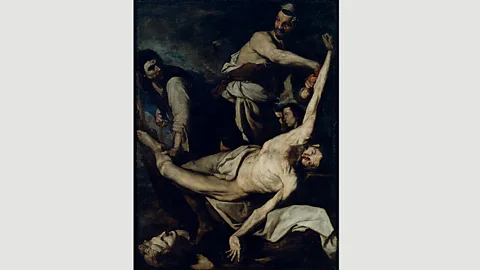

The show’s examination of the alarming allure of choreographed cruelty concludes with a display of Ribera’s lyrically lurid masterpiece, Apollo and Marsyas, painted in 1637. Returning to one of the artist’s favourite themes, the skinning alive of traumatised bodies, the work depicts – on a disturbingly grand scale – the horrendous execution of the satyr Marsyas, pitilessly punished for losing a musical competition to Apollo. Ribera is ghoulishly complicit in Apollo’s sadistic torment of Marsyas.

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, NaplesLike a maestro of misery, the artist conducts, brushstroke by brushstroke, a mute symphony of mellifluous brutality. Our eyes listen in revulsion as discordant notes are shredded from the wrenched body of Marsyas, which Ribera has laid out before the god of art and music like a howling harmonium. “Every detail,” as Gautier noted with mingled awe and disgust, “is rendered with horrible truthfulness”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.