The women Impressionists forgotten by history

National Gallery of Art, Washington

National Gallery of Art, WashingtonRespected by their peers and the public at the time, Morisot and Cassatt were distinguished painters who have since been dismissed by art history.

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt were both leading figures in the Impressionist movement, lauded by their peers and critics alike. Morisot was one of the founding of the group. Her enigmatic portrayal of the Parisian woman, combined with her revolutionary experiments with the concept of ‘finished’ and ‘unfinished’ in her painting, made her one of its most adventurous spirits. Cassatt had the distinction of being the only American to exhibit with the Impressionists. Her uniquely modernist interpretations of traditional themes such as the mother and child brought her international recognition.

More like this:

However the radical nature of Morisot and Cassatt’s work was frequently ignored by critics who couldn’t see beyond their ‘feminine’ subject matter and later art historians would dismiss them as ‘secondary’ figures in the movement. Today, while their male contemporaries Monet, Manet, Degas and Renoir are household names, far fewer are familiar with Morisot or Cassatt. This year, two major exhibitions, at Musée National Des Beaux-Arts Du Québec and The Musée Jaquemart André, Paris, have sought to rectify that.

Musée d’Orsay

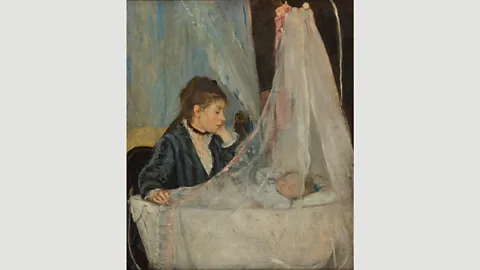

Musée d’OrsayMorisot was at the very heart of the Impressionists. Manet was a great irer of her work and it was he who invited her to them. She was also married to his brother Éugene. Even before she ed the Impressionists, Morisot had created highly innovative depictions of the modern woman. Two of her most celebrated works, The Cradle (1872) and Interior (1872), reveal her innate capacity to show “the complexity of human beings”, says curator Nicole R Myers. There is a sense of ambiguity that would remain throughout her work. The mother gazes at her child in a manner which could denote tiredness, boredom or even regret, whilst the striking figure in Interior has an expression which is equally hard to read. There’s always a sense of “more than meets the eye”, says Myers.

Once in the bosom of the Impressionists, Morisot began to make the figure of The Parisienne her own. The concept of this fashionable woman “was really being formulated in her lifetime and was seen in Paris as the epitome of modernity”, says Myers. “So if you’re staking a claim as a great modern painter, as Morisot was, the subject itself was really contemporary and fresh.”

Toledo Museum of Art

Toledo Museum of ArtUsing loose, gestural brushstrokes, she gives her women a profound psychological presence whether reading, dressed for a ball or performing their toilette. They are often portrayed by a window or on a balcony as if on the threshold of some new discovery or possibility. “She was obsessed with the ing of time, this vision of life that you cannot really grasp,” says co-curator Sylvie Patry.

By the late 1870s, Morisot was recognised in the press as holding a central place in Impressionism, but her innovative aesthetic was seen as a result of her ‘feminine vision’. While the paintings of her male peers were hailed as ‘original’ or ‘vigorous’, hers were ‘charming’, ‘gracious’ or ‘delicate’.

Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of ArtFrom the 1880s her compositions were frequently influenced by the Rococo, which was undergoing a revival in at the time. She took select aspects such as bright pastel hues or depictions of sensual femininity and adapted and modernised them to such an extent that their source material is scarcely evident. In Before the Mirror (1890), in which a scantily clad woman fixes her hair, she turns what would have been a titillating scene in the 18th Century into a virtuoso display of colour and technique.

But it was her experiments with the concept of ‘finished’ and ‘unfinished’ in her painting that showed “she was one of the most audacious, the one who really pushed boundaries”, says Patry. In Woman Reading in Grey (1879), the figure almost dissolves into the background and the edges are left uncompleted.

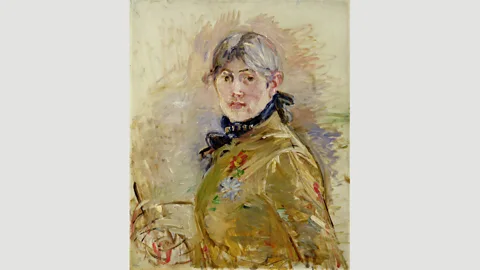

Musée Marmottan Monet

Musée Marmottan MonetFor this she was heavily criticised, with many seeing her startling innovations as a weakness of her sex. But her peers had no such doubts. A year after her untimely death in 1895, they organised what remains the largest retrospective of her work to date as a fitting tribute to her talent.

Modern women

Cassatt was a painter with an unstinting belief in her abilities who was equally happy to challenge convention. Her earlier Salon successes could have secured a lucrative career back home but, alone among the US artists in Paris, she was drawn to the free-spirited thinking of the Impressionists.

Degas had seen her work in 1874 and greatly ired it. The two became firm friends and he provided the model for Little Girl in a Blue Armchair (1877-8), which in many ways can be seen as her first Impressionist painting. The stunning portrayal of a young girl lolling inelegantly on an armchair with an expression that suggests modelling was far from her occupation of choice, was a clear indication of Cassatt’s innate ability to capture the inner life of her subjects.

National Gallery of Art, Washington

National Gallery of Art, WashingtonShe knew that the loose brushwork and bright background was unlikely to be appreciated by the jury of the Exposition Universelle to which she submitted it in 1878, but did so all the same. When it was turned down, “it was proof that she was now a bona fide modernist and part of the Impressionist rebellion,” says curator Nancy Mowl-Mathews.

Degas invited her to officially the group and she made her debut with them in 1879, receiving favourable reviews from the French press even if the Americans were less impressed with her new direction. “I feel sorry for Mary Cassatt... why has she gone astray?” sniffed The New York Times.

RMN-Grand Palais / Image of the MMA

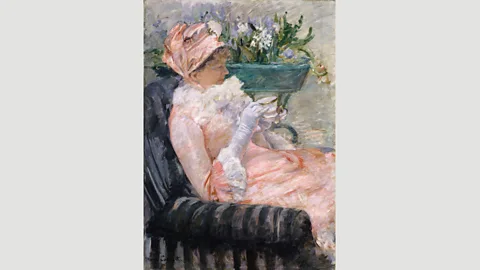

RMN-Grand Palais / Image of the MMACassatt became renowned for her portrayals of modern women which she painted with a unique respect. In a painting such as The Cup of Tea (1881), in which her sister Lydia is depicted in an elegant pink dress taking afternoon tea, it is clear that Cassatt’s interest lies more in the mind of her subject than her outer appearance. “She was really trying to capture the idea of thinking,” says Mowl-Mathews.

In later works such as Young Women Picking Fruit (1892), the women have a “goddess-like monumentality,” says Mowl-Mathews. Critics frequently commented on the unattractiveness of her models, but this was a deliberate choice of Cassatt’s, who was determined to prove that she could create stunning works of art whilst ignoring traditional concepts of beauty.

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Carnegie Museum of Art, PittsburghIn the 1880s, she began painting mother and child images. Cassatt delighted in the challenge of painting a child’s flesh and excelled in capturing the delicate nuances of skin tone. She would often adapt the Symbolist technique of using ordinary objects as religious symbols such as the mirror which hovers halo-like above its subjects in Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror) (1899), which Degas referred to as “the greatest painting of the 19th Century”.

These paintings were greatly ired on both sides of the Atlantic, even if US critics were more inclined to debate whether the mothers were American or French than fully comprehend her subtle imagery.

RMN-Grand Palais / Image of the MMA

RMN-Grand Palais / Image of the MMAThe fact that Cassatt was an American painting in an unequivocally French style is undoubtedly one of the major reasons that her role in Impressionism is underappreciated today. Curators are unsure whether to hang her in the American or European sections, leaving her work in limbo.

Hopefully these exhibitions will make it much clearer where both Cassatt and Morisot belong – side by side with the other greats of Impressionist painting.

Berthe Morisot - Woman Impressionist is at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, Québec 21 June – 23 September 2018, The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia 20 October 2018 – 14 January 2019, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 24 February – 26 May 2019 and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris 17 June – 22 September 2019. Mary Cassatt - An American Impressionist in Paris was at The Musée Jaquemart André, Paris.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.