Albrecht Dürer: The painter with 'a magical touch'

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, ViennaOriginally finding fame for his woodcuts, the 16th-Century German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer “collapses the world” between observers today and his paintings created 500 years ago.

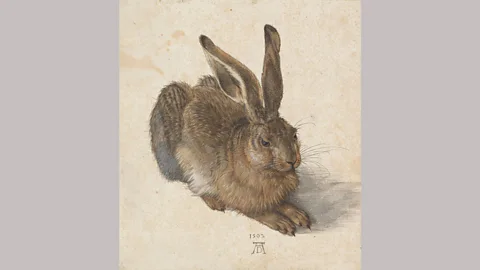

If you look closely, very closely, you can see it in the corner of the hunkered hare’s eye: not merely a pair of concentric glints echoing from its dark cornea, but a portal to the past. A miracle of focused observation and precise draughtsmanship, the famous watercolour, which faithfully transcribes every soft filament of the mammal’s fur, was created by pioneering German Renaissance painter, printmaker, and theorist Albrecht Dürer in 1502. It is now among the highlights of a new exhibition at the Albertina Museum in Vienna devoted to Dürer’s genius – an event that marks only the ninth time that the painting has ever been displayed in public.

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, ViennaThe reverberating gleam in the hare’s right eye, according to Christof Metzger, who curated the exhibition of more than 200 paintings, drawings and prints, is actually a reflection from inside Dürer’s studio, where the work was made – a magical touch that collapses the distance between observers of the masterpiece today and the bygone world that the artist inhabited half a millennium ago. “It’s really fascinating,” Metzger explained to BBC Culture about the most popular work in the Albertina Museum’s collection. “This animal materialises on paper in his workshop, and in the eye of the painted hare you can see his workshop’s window.”

More like this:

- Félix Vallotton: A painter of disquiet and menace

Is it indeed ‘the glazing bars from the window in the painter’s studio’, as the accompanying catalogue describes it? That seems to be the scholarly consensus, though the stretched shape of the beguiling glisten is ambiguous, and conjures something more sacred: the tall parallel panes of painted glass that one finds in the high windows of a cathedral’s nave. Dürer’s decision to erase from the surface of his work any suggestion of the animal’s physical environment keeps its situation (and meaning) remarkably elastic. The shroud-like emptiness that surrounds the portrait transforms the marvel into something as mystical as it is material – a fiery figment of the imagination; a vision; a prayer.

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, ViennaIn the only other works by Dürer where hares figure – a woodcut from six years earlier, entitled The Holy Family with Three Hares (c1497), and an engraving created two years later, Adam and Eve (1504) – the animal finds itself entangled in overt religious symbolism. But here, the hare is free to fidget in the minds of those who encounter it – as teasingly evasive in spirit as it is fixed physically in pigment and paper.

How, exactly, Dürer managed to capture the skittish creature with such painstaking rigour – without the aid of taxidermy to hold the jittery jumper – still has bedevilled irers of the work for centuries. A photographic memory? A steady, stewy diet of jugged hare? “I think with detail studies,” Metzger posits, when asked how he believes Dürer pulled it off: “studies of the hare in different positions: sitting, springing, from the side, from the front. Drawings like this are often the basis for his watercolours. He observed the living animal and then maybe when he makes the watercolour, the poor little hare is already in Dürer’s kitchen. We do not know.”

What we do know, what we can feel, is the indispensable power of the sublime glimmers that bedew the hare’s eye. Remove those subtle sparkles and the soul of the work would be snuffed out, its magic extinguished. Glimpsed through the gleam of the hare’s intense, almost otherworldly eye, and Dürer’s other masterworks bristle too with such invigorating details – seemingly slight chroniclings that are so astute, so meticulous, their truth transports us and makes us feel as if we are seeing the Earth we inhabit for the very first time. “Many of his works, and you can see this in the exhibition, are really timeless – “his landscapes, his studies of animals, of plants, of persons,” Metzger says. He’s such a brilliant observer of his world, of his context, on the one hand, and on the other hand such a brilliant artist in his ability to fix on paper what he has observed in nature, which is really fascinating and fantastic.”

A master of the natural world

Frequently mentioned in the same breath as Young Hare is Dürer’s hypnotic study of a dishevelled scrap of seemingly random sward known simply as the Great Piece of Turf, a watercolour accented by pen-and-ink that the artist created the following year. His realistic articulation of every feathery fibre of cocks-foot, every soft serration of germander speedwell leaves, and the weightless sway of a sprawling tuft of Agrostis, or creeping bent, is truly breathtaking. Symphonic in its disorder, the study conjures from chaos a sense of organic rhythm undergirding all of life. What elevates the scene into the strangeness of a great work of art is its surreal suspension of plants to reveal below the soil-line the downward reach of their straggling roots, as if the patch of earth were levitating before us, ascending to heaven.

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, ViennaThe Great Piece of Turf and the Young Hare both belong to the Albertina’s permanent collection, which forms the basis of the exhibition. “We have a very large and important collection,” Metzger tells BBC Culture, “and for works on paper, maybe the most important collection in the world.” Why now? “We thought it is time to show Dürer again after the last exhibition which took place in 2003. It’s always the right moment for an Albrecht Dürer show.”

Taking flight

There is indeed something imperishably poignant and up-to-date about Dürer’s meticulous scrutiny of the natural world, which is now, in the light of anxieties surrounding climate change, as much a source of unease as wonder. The brutal beauty of his assiduous study Wing of a Blue Roller, a watercolour on vellum probably created a year or two before the Young Hare, is indicative of the artist’s unflinching eye. “The outspread wing takes up almost the entire surface of a nearly square sheet of parchment,” Metzger writes in the show’s catalogue, “and depicts every detail of its morphology with the highest degree of zoological accuracy: the reddish, cinnamon-coloured back plumage remaining near the tear, the secondary feathers in ultramarine, turquoise, pale green and off-white, as well as the primary feathers ranging in colour from white and azurite to bluish black.

“He even applied the finest of gold lines to his depiction of the dead animal’s breast plumage in order to imitate its iridescent lustre.”

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, ViennaIn art history, we’re rarely accustomed to seeing such resplendent plumage unless it is flapping spiritually from the shoulders of the Archangel Gabriel in depictions of the moment he informs the Virgin Mary that she will give birth to Christ, such as Fra Angelico’s celebrated fresco The Annunciation. But in Dürer’s work, the soaring majesty of uplifting colours is held in cruel check by the spectre of violence that ripped the wing from the bird’s torso, displacing the specimen to a decidedly secular context. Seen in the light of present-day unease about the damage humans are inflicting on the natural world, Dürer’s watercolour ruffles with prescient profundity.

Born in Nuremberg in 1471, Dürer rose to prominence in his 20s as a master of woodcut prints. Following stints studying in Colmar, Strasburg, Frankfurt and Venice (where he honed printmaking techniques), he returned to Nuremberg in 1495 and established his own workshop, where he quickly began to build a formidable reputation. The Albertina exhibition displays many of the finest works that Dürer created in the ensuing years, from collections around the world, including such masterworks as the Adoration of the Magi (on loan from the Uffizi), Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum), and Christ among the Doctors (from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid).

Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

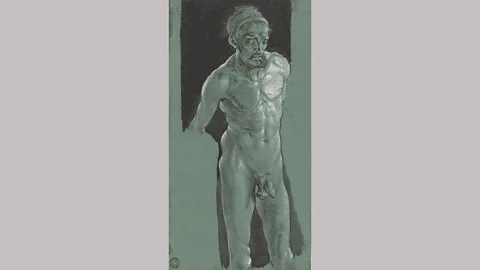

Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli UffiziAre there any surprises? “We have a very interesting example in the exhibition,” Metzger says, “of a self-portrait as a nude.” He’s referring to a rather unsettling ink-and-whitelead drawing on green paper that shows the naked artist wearing only a hairnet, framed by an abstract field of self-abnegating black. “You see him from his legs up completely naked. We do not know how Dürer made this. With only a small mirror he constructed his naked body. His body is absolutely detailed in the way it’s observed and drawn, but it’s fragmented. The arms are missing. The legs are missing. It’s only the torso of his body.”

Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Klassik Stiftung WeimarYet it is the work’s very distedness that paradoxically pulls it together into something pulsing and intense. Dürer’s ability to spin into existence from an almost miserly economy of strokes “a person filled with life whom you can meet on the street 10 minutes later”, as Metzger puts it, is exhilarating. “In my opinion, the exhibition is really a once-in-a-lifetime possibility. We are really trying to give an impression of his whole cosmos.” Through Dürer’s fastidious eye we find ourselves transported to another reality – a world we never knew we knew.

Albrecht Dürer is at Vienna’s Albertina Museum until 6 January 2020.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.