Félix Vallotton: A painter of disquiet and menace

Kunsthaus Zürich

Kunsthaus ZürichSwiss-born artist Félix Vallotton created disquieting paintings that conjure a sense of mystery – and menace, writes Kelly Grovier.

The key to unlocking the mysterious magic of Swiss-born artist Félix Vallotton, whose paintings and woodcuts are the subject of a major exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in London, can be found in a scene from a novel no one re: La Vie Meurtrière (or The Murderous Life), which Vallotton wrote in 1907, when he was 42. In it, Jacques Verdier, the narrator of this fictionalised autobiography, recalls an incident from childhood when he and his friend Vincent were walking atop a riverside wall. Vincent was striding in front, struggling to keep his balance on the stone wall, when suddenly the setting sun threw Verdier’s shadow forward, startling his friend. Vincent slipped and fell into the water, causing serious damage to his head.

Nora Rupp, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

Nora Rupp, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de LausanneWas Verdier responsible? Vincent thought so, and before long everyone else did too. It was, after all, some dark aspect of Verdier that had, in a sense, whether consciously or not, lunged forward and tripped his friend up, causing his injuries. But are we really responsible for the misdemeanours of our silhouettes? Is the shape of our lives determined as much by the consciousness of shadows as it is by the intentional actions we deliberately take? As the novel unfolds, Verdier’s ill-starred shadow hangs over one suspicious incident after another – from the death of an engraver (who accidentally stabs himself with a copper burin when spooked by Verdier’s presence) to that of an artist’s model, who slips when reaching for Verdier’s hand and falls fatally into a scorching stove.

The worlds that Vallotton conjures, whether in word or image, are invariably defined by a conspiracy of shadows. They whisper in secret. They frame us. Take, for example, Vallotton’s intriguing gouache-on-cardboard interior, La Visite (The Visit) (1899) – one of the stand-out works on display in the exhibition. At first glance, the scene seems innocuous enough, tender even: a man and woman, dressed to the nines, are locked in close, as if reliving the romantic embrace of the final dance they’d enjoyed earlier that evening before returning home.

Kunsthaus Zürich

Kunsthaus ZürichLook a little closer, however, and an awkward stiffness in the woman’s neck is echoed by the backwards roll of her tightening shoulders. She’s tense, scared. Her left hand, on further inspection, is not cradled consensually in a clasp with his right hand, but rather is restrained by it. This is no dance. It's a prelude to an assault. He’s bracing for a struggle that he knows is inevitable, because he’s orchestrating it. That the two are on the verge of tumbling into an abyss of violence is most powerfully portended by the commingled spill of their entangled shadow. Having already begun to devour her legs, their blurred shadow bleeds out aggressively to the right, engulfing a bookcase that one imagines is filled with Gothic tales of stranglings and poisonings he no doubt collects. A displaced cushion on the carpeted floor, about to be swallowed by the plush maw of the velvet sofa, which itself seems woven more from shadow than thread, is a further clue that things are about to get troubled. To the left, a bedroom yawns open like a cage.

The Baltimore Museum of Art/ The Cone Collection/ Mitro Hood

The Baltimore Museum of Art/ The Cone Collection/ Mitro Hood“I think enigma is what it’s about,” Ann Dumas, who conceived and curated the exhibition Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet, tells me when I ask her what underlies the vexing narratives of Vallotton’s art. “It’s always a man and a woman interacting in a more than slightly claustrophobic, bourgeoise interior,” she explains. “You never quite know what the relationship is, what the transaction is. You always get the sense it is some kind of illicit relationship.”

A conspiracy of shadows

Vallotton was born in the Swiss city of Lausanne in 1865 and moved to Paris when he was 16 to pursue his ambition of becoming an artist. He would live in for the rest of his life, becoming a citizen in 1900. Resuscitating a tradition that had steadily declined in popularity and prominence since the Renaissance, Vallotton first attracted attention in the early 1890s as a virtuoso maker of woodcut prints. He shone a light on the lust, greed, hypocrisies of the middle class in acerbic scenes characterised by their stark, black-and-white attitude to social mores.

Musées d’art et d’histoire, Ville de Genève, Cabinet d’arts graphiques

Musées d’art et d’histoire, Ville de Genève, Cabinet d’arts graphiquesIn one such arresting vignette, Intimités V: L'Argent (Intimacies V: Money), created in 1898, the year before Vallotton painted The Visit, we see the artist experimenting with just how far shadow, as a palpable existential, psychological and physical aspect of the human condition, can monopolise an image. Here, a man desperately trying to explain himself to a woman whose long-suffering soul has already checked out of the room and relationship in which we find them, is about to be consumed entirely by an accumulating shadowiness of Self that inundates the image from right – one that threatens to submerge the two forever in its tsunami of asphyxiating darkness.

For a time, Vallotton aligned his way of seeing with the short-lived mystical group of symbolist artists known as ‘Les Nabis’ (Arabic for ‘The Prophets’), which included Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard and disbanded in 1900. Though he would retain the luscious brushwork he honed in the company of the Nabis, Vallotton was never a heartfelt follower (the others called him ‘the foreign Nabi’) and would go on to cultivate a strangeness of storytelling all his own – one that balances a realism of figurative form with a mystery of amorphous shadow.

Mairie de Bordeaux/ F Devel

Mairie de Bordeaux/ F Devel“Vallotton has never quite been given the exposure he deserves,” argues Dumas, who has organised the first ever show in Britain to feature the artist’s paintings. (The last show in the UK devoted to his work was over 40 years ago and it focused almost entirely on his prints.) Why has Vallotton struggled to gain traction outside his native Switzerland, unlike other former of the Nabis group? “I think he’s a tougher artist than they are,” Dumas tells me: “he’s a strange and dark character. It may also have something to do with the fact that he was Swiss. So many of his works ended up in Switzerland, partly because his brother, Paul Vallotton, was an art dealer who established himself in Lausanne. He sold a great deal of his brother’s work to Swiss museums and private collectors, so Vallotton wasn’t in the mainstream of French art like Bonnard and Vuillard.” In the century since his death, Vallotton has largely fidgeted in the shadows of those two painters, as it were.

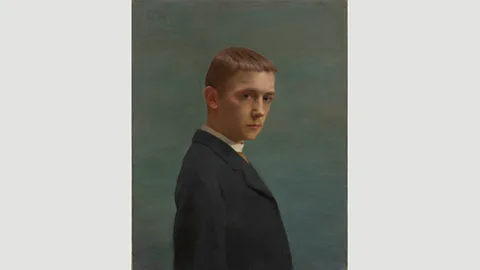

Career-spanning in its scale, the exhibition takes visitors from the wrestlings of a young artist struggling to find his visual voice amidst the feverish experimentations of fin-de-siècle Paris, to one who, after achieving financial stability with his marriage to a wealthy widow in 1898, was determined to make an indelible mark on the unfolding story of art. “Visitors may be surprised,” Dumas tells me, “by how much he changes over time.” She points, in particular, to how “he becomes obsessed with the French neo-classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and develops this cold hard-edged realism”.

SIK-ISEA, Zurich

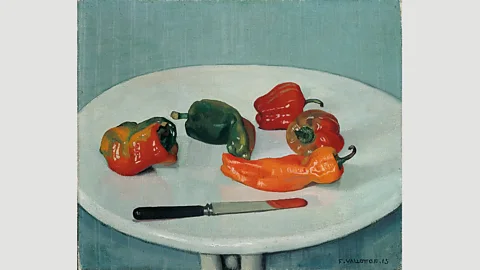

SIK-ISEA, ZurichTo my eye, even in such hard-edged works – ones that initially appear forensically scrubbed of the menacing shadows that dominate his earlier woodcuts – a subliminal darkness subsumes the narrative, dislocating its superficial realism, taking us to a place that lies below the surface of seeing. In Red Peppers, for instance, painted in 1915 when cultural consciousness was preoccupied with the horrors of the World War One, a sharp glisten of waxy orange, red, and green capiscums, offered to us on a crisp white plate, is barely intruded upon by the faintest of subtle shadows falling palely to the right.

Here, physical shade has been superseded by a darkness of psychic intrigue that sculpts itself instead into the black handle of the knife that lies before us. Its blade gleams with a murderous, haemoglobin glow that cannot be attributed to any realistic reflection of the peppers themselves. Something sinister vibrates outside the frame. The artist’s haunting shadow never fully fades.

Kunsthaus Zürich

Kunsthaus ZürichIn Sandbanks on the Loire (1923), one of the last paintings Vallotton undertook, created two years before his death – a work that Dumas describes as having “a slight unstated sense of menace to it” – the mysterious tension between object and shadow remains on full display. A fisherman has made his way to an eerily still inlet whose glassy water mirrors the calm summer sky. At first glance, a softness of dry, undulating banks and the billow of trees in fullest leaf seem the very picture of peaceful contentment.

But, as always, the shadows tell a different story. More angular than can be ed for by the pillowiness of the leafy branches from which they fall, the clapboard shadows are oddly boxy in their secret carpentry; coffin-like. Suddenly, the small boat on which the fisherman has conveyed himself to this curious elsewhere seems more like a casket than a skiff. The murky message is clear: there’s no coming back from where the shadows take you.

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet is at the Royal Academy, London until 29 September 2019.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.