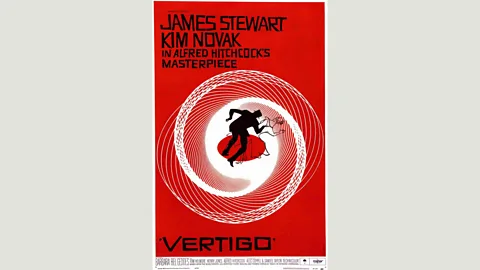

How Vertigo foreshadowed ‘catfishing’, AI and #MeToo

Alamy

AlamySixty years since it was released, Vertigo resonates powerfully in the age of the internet, virtual reality and artificial intelligence, writes Nicholas Barber.

Vertigo gets better with age. Alfred Hitchcock’s mind-bending mystery wasn’t a critical or commercial hit when it was released 60 years ago, and in an interview with Francois Truffaut in 1962, Hitchcock himself classed it as “a failure”. But few failures have gone on to be so successful. In the critics’ poll conducted once a decade by Sight and Sound magazine, Vertigo was ranked, in 1982, as the seventh best film ever made. By 1992, it had crept up to fourth place; by 2002 it was second only to Citizen Kane; and in 2012 Vertigo overtook Orson Welles’ masterpiece to take the top spot.

Why has its reputation climbed to such dizzying heights? One obvious reason is that the film drips with the kind of toxic cynicism which appeals to critics in retrospect more than it does to Saturday-night cinema-goers. In a canon not short of gruesome murders and cruel betrayals, Vertigo stands out as Hitchcock’s most mercilessly bleak work. Two women die horribly, the hero’s sanity is shattered, and there is no indication that the urbane villain will be punished. You can see why it frustrated viewers who were in the mood for a Jimmy Stewart adventure yarn in 1958.

More like this:

Another reason why Vertigo now towers over the competition is that its themes have become ever more relevant. It’s not one of those films which predict the future, and it’s not a science-fiction movie by any stretch of the imagination, but it was certainly way ahead of its time. When you watch Vertigo in the age of the internet, virtual reality and artificial intelligence, it resonates as loudly as a church bell.

Alamy

AlamyAdapted from a French novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, and scripted by Alec Coppel and Samuel A Taylor, Vertigo stars James Stewart as John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson, a San Francisco police detective who retires with a bad back and a worse case of acrophobia, or fear of heights. With nothing better to do, he accepts a job offer from an old college buddy, a shipbuilding magnate named Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore). His assignment is to keep an eye on Elster’s wife Madeleine (Kim Novak), not because she is having an affair, but because she is behaving strangely: every now and then her own personality fades away to be replaced by that of Carlotta Valdes, a relative of hers who committed suicide a century earlier.

As Scottie follows Madeleine through San Francisco’s steeply inclined streets – it’s the worst possible city for someone with acrophobia – the film pretends to be a supernatural chiller: the spine-tingling tale of a woman who is either possessed or insane. But this storyline comes to an abrupt, shocking conclusion when Scottie sees Madeleine falling to her death from a bell tower. Desperately infatuated, he is traumatised for months. So when he spots Judy, a shop assistant who looks like Madeleine, he coerces her into changing her clothes and hairstyle until she is indistinguishable from the woman he loved and lost. The twist is that Judy was that very woman. The ‘Madeleine’ who bewitched Scottie was Judy all along, styled by Elster as part of a scheme to murder his actual wife. And the person Scottie saw plunging from the tower was the real Madeleine, not the counterfeit one.

Alamy

AlamyAll clear? Probably not. But the makeover scenes have led to Vertigo being described as Hitchcock’s ‘confessional’ (to borrow Roger Ebert’s word): his brazen acknowledgement that he tried to mould every actress he hired into an ideal ‘Hitchcock blonde’. And while this has always been one source of the film’s fascination, it’s an even bigger factor now. In the past year, since Harvey Weinstein’s alleged crimes against women were brought to light, we’ve had to think harder about the sexist bullying perpetrated by Hitchcock and his peers. Vertigo has become a key text in the prehistory of the #MeToo movement.

Virtually virtual reality

But that’s not the only facet of the film that is weirdly contemporary, six decades after its premiere. To focus solely on the idea that Scottie embodies all of Hitchcock’s control-freak tendencies is to overlook the fact that Scottie is being controlled, too. All the time he is stalking Madeleine – or the woman he presumes is Madeleine – he isn’t a svengali but a stooge: a lovelorn dupe who is being suckered by a beautiful femme fatale, just like the hapless heroes of so many film noirs before him.

What’s unusual about his predicament is that Judy that doesn’t use her own feminine wiles to seduce him. Rather, she is playing a role which was written for her by Scottie’s pal Elster – and that’s the aspect of the con which upsets Scottie the most. “Did he train you,” he rants when he realises he’s been tricked. “Did he rehearse you? Did he tell you exactly what to do, what to say?”

The kicker is that, as Elster is one of “the old gang” from college, we can assume that he tailored his plan to fit Scottie. Another college friend, Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes), sums up the detective as “the bright young lawyer who thought he was going to be chief of police one day”. Instead, he wound up as an invalid with a corset and a walking stick. But the scenario concocted by Elster allowed him, briefly, to be a winner again: a knight in shining armour coming to the aid of a damsel in distress. What enrages Scottie at the film’s feverish climax is the knowledge that this flattering and potentially redemptive narrative was entirely false. It was a sham, a simulation; it was virtually virtual reality.

Alamy

AlamyThe depths of Elster’s deception, and Scottie’s self-deception, would have been disturbing enough in 1958, when audiences were used to seeing Stewart as a true-blue hero who always got the girl. But at least they could reassure themselves that the plot was “devilishly far-fetched”, as the New York Times put it. No one except a Hitchcock villain would ever attempt a ruse as complicated or as risky as Elster’s. After all... using information you’d gathered about somebody in order to construct a bogus persona to entice and exploit them – who could do a thing like that?

These days, unfortunately, the answer is: pretty much everyone. Thanks to the internet, the world is full of people crafting fake identities: Judy and Elster were simply ‘catfishing’ before the term was invented. And that’s why Vertigo is so horrifying today. To watch Scottie’s torment now is not to smirk at how contrived it all is, but to wonder whether we could be hoodwinked in a similar way by a dating app, a Facebook ‘friend’, a Twitter bot, or a marketing algorithm. Could we be taken in by an image of a romantic partner, and an image of ourselves, which has been formulated, coldly and calculatingly, for that very purpose?

This question has been asked regularly in recent science-fiction films. Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, Spike Jonze’s Her, and Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 all worry about whether we can distinguish between the organic and the artificial, and whether the distinction matters. Joaquin Phoenix’s character in Her, for instance, rejects a blind date played by Olivia Wilde because he’d rather snuggle up with his smoky-voiced operating system. But Vertigo got there first.

Alamy

AlamyIt’s clear that the aforementioned Midge is carrying a torch for Scottie, even if she broke off their engagement years earlier. And it is clear that she isn’t some ethereal dream girl, but a flesh-and-blood modern woman. When we first see her, she is sketching a lingerie ment. “What’s this doohickey?” asks Scottie – a quintessentially James Stewart-ish question. “It’s a brassiere,” teases Midge. “You know about those things. You’re a big boy.” But it might have been more accurate to say that Scottie is a little boy – someone so immature that he turns down dinner and a movie with the loyal Midge (and, later on, with Judy) to pursue Madeleine, a living doll who has been manufactured to pique his interest. And that’s what prompts Scottie’s metaphorical downfall – as well as Judy’s literal downfall (yes, she ends up tumbling from the bell tower, too). He chooses fantasy over reality, much like the men in Westworld and The Stepford Wives. And in the 21st Century, when we spend so much of our lives online, quite a few of us are making the same mistake.

Alamy

AlamyAgain, I wouldn’t argue for a moment that Hitchcock was warning us about algorithms or the internet when he was making Vertigo. He wasn’t pondering the dangers of AI or VR. But rewatch that classic credits sequence designed by Saul Bass. First there is a black-and-white close-up of a woman’s mouth. The camera moves up to her eyes, which look right and then left. As the camera zooms in on one eye, the screen is tinted red, and the eye widens. An intricate purple vortex starts to spin in its pupil.

The film that follows is, of course, a Hitchcock suspense thriller. But if it did happen to be the story of an android that had been built to mesmerise her unsuspecting prey, it could hardly have had a more appropriate opening than that.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.