Why Hitchcock’s Kaleidoscope was too shocking to be made

Alamy

AlamyInspired by a real-life serial-killer case, Hitchcock’s vision for Kaleidoscope was deemed too gruesome and sexually explicit for its time.

For all of his phenomenal achievements, Alfred Hitchcock is probably best known for Psycho, and in particular the scene in which – spoiler alert – a man dressed in his dead mother’s clothes stabs a naked woman in a motel shower. Audiences in 1960 were traumatised. In a recent documentary about that one scene, 78/52, Peter Bogdanovich re the “sustained shriek” that filled the cinema when Psycho premiered in New York. But Hitchcock had an even more shocking film planned just a few years later. It would have been called Kaleidoscope. Determined to catch up with Europe’s most innovative directors, Hitchcock wanted to apply their radical methods to one of his own typically dark narratives. If he had succeeded, we might currently be celebrating the 50th anniversary of a boundary-pushing, taboo-shattering masterpiece. But it wasn’t to be. Kaleidoscope was deemed so transgressive that not even the man behind Psycho was allowed to make it.

More like this:

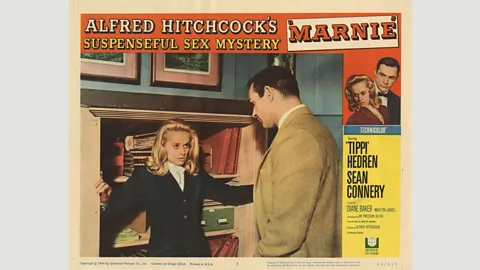

Hitchcock had hoped that the film would go into production in 1967. He had just been given an honorary Oscar, the Irving G Thalberg award, and Francois Truffaut’s book of interviews with him had just been published, so his place in the pantheon of all-time great directors was secure. On the other hand, his last two releases, Marnie and Torn Curtain, had both been disappointments. Torn Curtain, Hitchcock’s 50th film, had gone down especially badly when it came out in 1966. “There is a distracted air about the film,” wrote Richard Schickel in Life magazine, “as if the master were not really paying attention to what he was doing.” Schickel went on to complain that the “mechanical” Torn Curtain was the work of a “tired” Hitchcock repeating “past triumphs”. Something had to be done.

Back in 1964, Hitchcock had ed a story outline with the Writers’ Guild. Inspired by two English serial killers who were hanged in the 1940s, Neville Heath and John George Haigh, it was to be a kind of prequel to 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt. In that film, Joseph Cotten plays the so-called Merry Widow Murderer. We don’t see him murdering any widows, merry or otherwise, but Hitchcock felt that he could be more explicit in the permissive ‘60s. Not only could he show a serial killer seducing and butchering his victims, but he could make that serial killer the film’s central character.

Alamy

AlamyThe director asked Robert Bloch, the author of Psycho, to write a novel based on his idea, which he would then adapt for the screen. Bloch supposedly found the material too ‘disturbing’ in 1964, but when Hitchcock commissioned his old friend Benn Levy to rough out a script in 1966, Levy had no such qualms. His treatment begins with the macabre comment that “The Neville Heath story is a gift from heaven.” He asserts that one of the seduction sequences “should be the most bloodcurdling scene ever seen on the screen” and that the police’s manhunt should be seen “more from the angle of the pursued than the pursuers”. But Hitchcock went further. He wrote his own draft of the screenplay, the first time he’d done so since 1947’s The Paradine Case.

Set in New York, this version of Kaleidoscope reimagines Heath as a handsome mummy’s boy named Willie Cooper. His homicidal mania is triggered by water, hence the locations of the script’s three pivotal scenes: a waterfall where he takes a United Nations employee; a rusting warship in a dockyard; and an oil refinery where his target is actually a police detective who risks her life to entrap him. Years before Halloween and the Texas Chain Saw Massacre, these scenes would have been harrowingly gruesome. To quote Hitchcock’s screenplay: “The CAMERA ARRIVES on the girl’s abdomen where WE SEE rivulets of blood.”

Alamy

AlamyAnd that wasn’t all. Willie was to have bodybuilding magazines stashed around his room, so as to suggest that he was gay, and he was to be caught masturbating by his mother. There was also to be graphic nudity: about an hour of test footage was shot around New York, and much of it depicted semi-naked models. Even Truffaut was concerned. “Of course, there does rather seem to be an insistence on sex and nudity,” he said in a letter to Hitchcock after he’d read the screenplay. But he was willing to give the master the benefit of the doubt. “I know that you shoot such scenes with real dramatic power, and you never dwell on unnecessary detail.”

Alamy

AlamyBut this wasn’t to be a typical Hitchcock production. He was going to experiment with an unknown cast, handheld cameras, natural light and location shooting – anything to prove that he wasn’t “tired” or “distracted”. He hired two further writers, Hugh Wheeler and Howard Fast, to polish his screenplay, the latter of whom would recall his revitalised sense of purpose in Patrick McGilligan’s biography, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. “My God, Howard,” Hitchcock said to Fast. “I’ve just seen Antonioni’s Blow-up. These Italian directors are a century ahead of me in of technique! What have I been doing all this time?”

Ahead of its time?

Alas, executives at MCA/Universal didn’t share his enthusiasm. Hitchcock went into a studio meeting armed with photos, footage and a detailed script that included 450 specific camera positions. He was “further in the development of this project than any other unrealised production,” writes Dan Auiler in his book, Hitchcock Lost. But it was all in vain. “In no time at all they rejected the script and told Hitchcock they couldn’t allow him to film it,” said Fast.

Alamy

AlamyRaymond Foery, the author of Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece, places the blame with Lew Wasserman, the studio’s owner. “Wasserman had known Hitchcock since the late ‘40s and had even been his agent,” says Foery. “But he wanted Universal to leave behind its previous reputation as a maker of lowbrow horror films. This project seemed to him to be too lowbrow, and not within the realm of what he wanted Hitchcock to do.”

Whatever the reasoning, Hitchcock was distraught. “They had belittled his attempt to do precisely what they had been urging him to do,” said Fast, “to attempt something different, to catch up with the swiftly moving times.”

Alamy

AlamySome of his 1967 concepts eventually wormed their way into 1972’s Frenzy, a serial-killer shocker with an unstarry cast, some nudity, and a gruelling rape-and-murder scene. But Frenzy, which was set in London, was conventional compared to what Hitchcock had envisaged for Kaleidoscope. Besides, US cinema had already embraced European new-wave innovations by this point in the ‘70s, so he had missed his chance to show Hollywood how avant-garde he could be. “Had the 1967 [Kaleidoscope] been produced,” writes Auiler, “its brutality and cinema verité style would have been ahead of the films of this period that did break down the studio’s stylised violence: Bonnie and Clyde, even Easy Rider.”

Alamy

AlamyJohn William Law, who discusses Kaleidoscope in his new book, The Lost Hitchcocks, believes that Wasserman wasn’t just worried about the film’s effects on Universal’s reputation, but on the industry which had grown around Hitchcock himself. “You have to realise that he was a brand,” says Law, “with TV syndication rights, a back catalogue of valuable films, books, magazines and a persona known around the world.”

Maybe so, but if Wasserman and MCA/Universal’s other executives wanted to protect the Hitchcock brand, they clearly didn’t understand it. They saw him, presumably, as the self-parodying, avuncular host of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV series and its spin-off literary anthologies and records. But, throughout a career spanning five decades, he had always catalogued humanity’s most violent and misogynistic impulses, and played with bold new cinematic approaches. If only he’d been able to make it, Kaleidoscope might have been the Hitchcock-iest Hitchcock film of all.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.