An unflinching look at Mississippi’s darkest moments

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

Mississippi Civil Rights MuseumThe new Mississippi Civil Rights Museum is an important stop for anyone interested in the US’ struggle for racial equality.

On a June night in 1963, Myrlie Evers was waiting for her husband Medgar to return from a civil rights rally when she heard a noise from their carport.

As the civil rights leader and father of three approached his home, white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith stepped out from a thicket of honeysuckle vines and fired a hunting rifle at his back. Medgar Evers staggered to the door, where his family found him bleeding to death.

Those moments flooded back as his widow toured the new Mississippi Civil Rights Museum a few weeks ago.

“I wept,” she said the day it opened in December 2017. “I felt the bullets, I felt the tears, I heard the cries. But I also sensed the hope.”

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

Mississippi Civil Rights MuseumYou may also be interested in:

• How Hiroshima rose from the ashes

The $90 million museum complex, located in the city of Jackson, presents a comprehensive and unflinching look at the US state of Mississippi’s darkest moments. It recounts the history of the civil rights movement beginning with the introduction of slavery in North America to the upheaval of the 1950s and ‘60s that eventually overturned segregation. It uses multimedia theatres showing archival footage of trials, protests and funerals, and artefacts like hooded Ku Klux Klan robes, a burned cross and the Enfield rifle that took Evers’ life. And it immediately makes Mississippi’s sleepy capital an important stop for anyone interested in the US’ struggle for racial equality.

“We’ve waited a long time for it,” said Reuben Anderson, Mississippi's first African-American Supreme Court Justice, explaining that it has been a 40-year effort to get the political and funding to open the nation’s only state-run civil rights museum.

Indeed, the institution fills a gap. Other states like Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee have for decades preserved and commemorated their civil rights history in museums, monuments and historic sites like Memphis’ Lorraine Motel, the site of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination. But until now Mississippi, a key battleground in the fight against segregation, had largely ignored its troubled past.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe timing seems appropriate, though. The institution opened just a few months before the 50th anniversary of King’s death, and also coincides with the news that more than a dozen states are banding together to promote a civil rights trail linking scores of sites across the country.

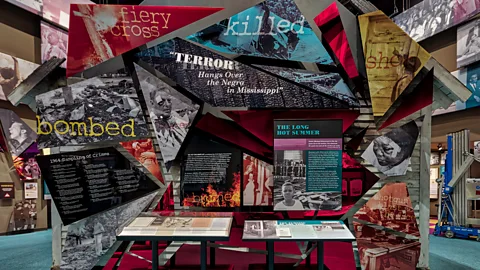

For many, the museum’s blunt presentations will be shocking.

The introductory gallery explains how enslaved Africans were first brought to the territory by colonialists in the 17th Century and explores the violence they faced. As visitors walk through the galleries, recordings lash out of the darkness with racial taunts: “Boy, get off that sidewalk,” and “Gal, you know you say thank you to me.”

“We want people to understand the emotional trauma that folks went through on a daily basis,” said museum director Pamela Junior.

Larry Bleiberg

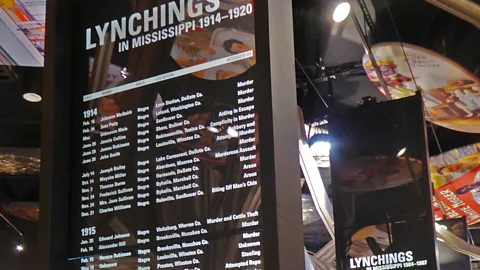

Larry BleibergBut other traumas were far worse. Six pillars list lynchings dating back hundreds of years – the names resurrected from the past and finally recognised.

One alcove, shielded from younger visitors, flashes historical photos of men hanging from trees, along with their names, locations and dates of death. The images are projected at an angle, so viewers unconsciously must tilt their necks, like those of the victims.

Junior says the museum felt it had to directly address the violence associated with the civil rights struggle. “You’re looking at how people are hanging, just thinking about what they saw as they died.”

While there’s no definitive number of victims, a recent study by the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative found 654 racially-motivated lynchings in Mississippi between 1877 and 1950. More died in the following decades of protest.

“There was really no choice in the matter. We tell the truth,” Junior said.

Cassandra Hawkins, a Jackson resident who volunteered during the museum’s busy opening weekend, said many people told her they appreciated the candour. “The real history is there. They don’t sugar-coat it.”

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

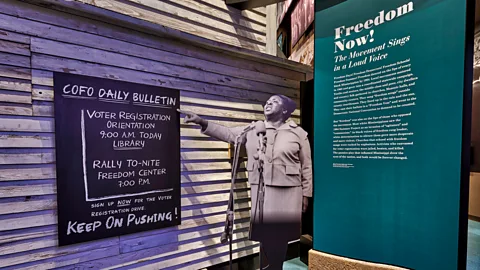

Mississippi Civil Rights MuseumThroughout the galleries, small immersive theatres cover key moments from the modern civil rights era, which gained a foothold as African-American soldiers stationed overseas during the Second World War returned to find discrimination and segregation back home.

Mississippi native Oprah Winfrey narrates a presentation on the 1955 death of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was visiting family in Mississippi. Accused of flirting with a white grocery store clerk, the clerk’s husband and his half-brother dragged the teenager from bed a few nights later, shot him in the head, tied his body with barbed wire to a 75lb cotton gin fan and threw him in the Tallahatchie River. The two men were later acquitted by an all-white jury.

Till’s mother held an open casket funeral so his injuries could be seen, and a photo of the boy’s mangled face was published in Jet magazine. The murder shocked the nation and galvanised the civil rights movement. The museum displays the original magazine as well as the doors of the Bryant Grocery store.

Another section addresses the 1961 Freedom Rides, the bloody crusade to protest segregated transportation facilities in the southern US states. Hundreds of the so-called riders arriving in Jackson by bus, train and plane were methodically arrested and sent to the infamous Parchman Farm prison, located on a former plantation. Their mugshots now line museum walls, and an interactive gallery reveals the stories of many, including Georgia congressman John Lewis, then a 21-year-old college student.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

Mississippi Civil Rights MuseumAn emotional video presentation explores the murders of 1964’s Freedom Summer campaign to African-American voters. Black state resident James Chaney and white student volunteers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman disappeared on a June afternoon. Their bodies were later found by the FBI, buried in an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi, and the footage of Chaney’s eulogy by a fellow activist still resonates across the decades as a cry for justice.

But the museum digs far deeper than these major exhibits. Nearly every Mississippi city and town had its own racial protest, and many get their first widespread exposure in these galleries.

One display outlines the ‘wade-ins’ in 1959, 1960 and 1963 to desegregate the Gulf Coast beaches of Biloxi. Another recalls the ‘read-in’ at Jackson’s whites-only public library, led by the Tougaloo Nine, a group of students from the city’s historically black college.

A touch screen explores the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a domestic CIA of sorts, which spied on citizens believed to desegregation. Other exhibits chart the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and their terrorizing night rides through black communities.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

Mississippi Civil Rights MuseumAlthough the stories are grim, there is the sound of hope in the air. At the heart of the museum, a towering 40ft sculpture called This Little Light of Mine pulsates every 30 minutes with the soaring melodies of gospel songs that inspired protesters and became a soundtrack to the era. When visitors are drawn by the music to the centre gallery, they trip electronic sensors. As the crowd swells, lights outlining the sculpture glow and intensify, and the music builds to a crescendo from individual voices to a choir.

Myrlie Evers-Williams, who remarried after her husband’s assassination and later delivered the invocation at President Barack Obama’s second inauguration, says the symbolism is clear. “You hear the sounds of horror, but you hear the sounds of coming together.”

more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.