Is oshi palav the 'king of meals’?

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriThis Tajik dish of rice, vegetables and usually meat, is said to bring families together, secure friendships and solve arguments – and may even have helped end civil war.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriIf you can say one thing about Tajik culture, it’s that people prioritise making time for others. Walk through a city and people are sitting on benches, chatting and relaxing. Show up at a stranger’s door and your hosts will welcome you with not only warm smiles but also a table laden with food and endless amounts of tea.

“In many big, industrial cities in Europe, people are so busy that they have no time for sharing anything – time, food or even just talking with each other,” said Munira Shahidi, a Tajik professor in Dushanbe who has lived in the UK. “They’re always running from place to place. We’re saying you can be very busy, but you should not forget to share your time and space with others.”

No dish is a better example of this generosity of spirit than oshi palav (pronounced ‘peel-OW’), often anglicised as ‘rice pilaf’. A slow-cooked mix of rice, vegetables and usually meat, oshi palav holds a special place in Tajik culture. It’s the main dish at celebrations and festivals, and ‘osh’, as it often is called, is said to bring families together, secure friendships, solve arguments – and may even have helped end civil war.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriTajiks refer to oshi palav as ‘the king of meals’.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriIn this rocky, remote country, the poorest in Central Asia, rice is precious. “Rice is a sacred grain. In Tajik culture, there is a saying that rice is the teeth of the prophet Muhammad,” said Dilshad Rahimi, deputy head of research at Tajikistan’s Institute of Culture.

Because oshi palav is meant to be eaten communally, that precious rice is rarely made in small amounts. One popular recipe for making osh at home is called ‘one-to-one’: 1kg of rice, 1kg of carrots and 1kg of lamb. At festivals and celebrations, meanwhile, it’s not uncommon to see a cook making the dish for more than 100 people at a time, standing over a steaming pot of rice wider than he is. Some of the most skilled cooks can even make the dish for more than 500 people at once.

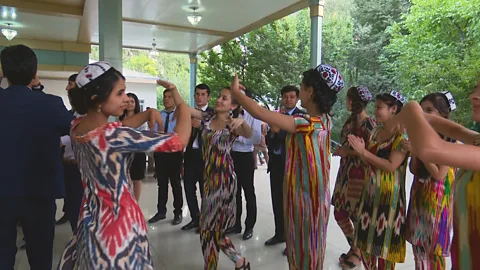

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriA source of national pride, osh appears at celebrations across the country – including festivals like this one in Panjakent.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriThe process of making oshi palav shows how Tajiks are generous with their time: from start to finish, the dish can take a couple of hours.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriFirst, ingredients like carrots, onions and garlic are fried in oil, usually in a pot over an open flame. Then water is added. Once it boils, rice is put into the same pot to simmer.

The resulting combination of firm-but-tender rice and rich oil is not only stick-to-your-ribs good, it’s a smart way to make simple ingredients taste decadent.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriFamilies with the means to do so tend to have oshi palav at home a couple of times a week. And when they want to meet friends, people will often go to a teahouse (like this one pictured) and have other dishes.

It is when guests are coming over, though, that osh always is the main event. “Maybe first they prepare soup, or prepare other dishes,” said Rahimi, who led a research group on osh for Unesco. “But the final dish must be palav.”

The tradition is so ingrained that there’s a running joke about the guests who refuse to leave someone’s home, even after midnight, because they haven’t yet been served osh.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriAs one oft-quoted saying puts it, “If there’s no osh, there’s no friendship.” Share osh, on the other hand, and you’ve laid the foundations for amity – even peace.

Osh is a key part of how Tajiks often settle disagreements. The action of exchanging osh between neighbours is interpreted to mean wanting peace with one another. And if people are arguing, it’s traditional for an elder to intervene and have the two sides work out their differences over a shared plate.

But the most dramatic example came during Tajikistan’s five-year civil war. In 1995, after three years of violence – by the end, up to 100,000 people were killed – the warring factions sat down to a plate of osh. It wasn’t a quick fix though; two more years of talks and complications followed. Even so, Tajiks often refer to the ‘palav of peace’ as the turning point for their country.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriEven how osh is eaten shows a sense of camaraderie. Traditionally, Tajiks share osh from one big plate, eating with their hands.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriNo-one can be sure exactly where and when oshi palav originated, but a rice and meat dish called ‘pulao’ first appeared more than 2,000 years ago in Sanskrit texts in India. In the 10th Century, the Persian scholar Avicenna became the first to write down how to prepare it. Today, versions of the dish are found throughout the region; variations are eaten as far away as Iran and India. In 2016, when Unesco named Tajikistan’s oshi palav to its list of intangible cultural heritage, it also gave Uzbekistan’s famous version, palov, its own listing.

“But specific to Tajik palav are two things,” Shahidi said. “The first is a special rice and the second is spices. The spices are from the mountains, as you can imagine, because our country is a mountainous country. And the rice grows around Panjakent: it is a bit bigger than usual rice and it is used for palav.”

Even so, within Tajikistan alone there are more than 200 variations of oshi palav. The classic version includes carrots, onions, garlic, lamb and spices like cumin or coriander. But ingredients like chickpeas, pumpkin or even lemon can be added, giving each dish different colours and flavours. Because recipes tend to be ed down between generations, one family’s or village’s particular version of osh is a key part of their identity and heritage.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda Ruggeri“As soon as anybody asks me about palav, it immediately reminds me of my childhood. The smell of that is still a part of my identity,” Shahidi said. “It gives a feeling of comfort and happiness, even in your mouth.”

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda RuggeriTajikistan’s tradition of sharing extends beyond guests: families also often cook oshi palav and take it to an orphanage or nursing home.

Amanda Ruggeri

Amanda Ruggeri“The main tradition in our culture is sharing – to share food with the others and especially to go to those types of places and making palav for them,” Shahidi said. “We believe that it is our human duty to share.”

Whether that is with friends, strangers, or even, in the case of peace palav, enemies, there’s no better example of that than osh.