How Japan’s tsunami-ravaged coastline is being transformed by hope

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIwate and Fukushima Prefectures were ravaged by the 2011 tsunami that precipitated a catastrophic nuclear disaster. Now, this tragic, beguiling region is welcoming travellers back.

Hope spiralled tender as a rice shoot along the resurrected Sanriku Railway Rias Line in north-eastern Honshu. Summer's blooms spilled from pots on station platforms; storybook houses peeped from the forests' folds; a man knelt beside the ice-blue river and cleansed a fistful of spring onions. Rice crops flashing by in the valleys were ripe for the harvest: their imperial yellow shimmer filled the windows as my friend and I rattled along this once-moribund coastline.

On 11 March 2011, communities along the north-eastern seaboard of Japan's biggest island, Honshu, were swept from their moorings when an earthquake measuring 9.1 on the Richter scale precipitated a tsunami of monumental proportion. Seawater barrelled into the saw-toothed shoreline, upturning infrastructure, buckling forests, flushing lives from every crevice. When the oily tide receded, little but splintered flotsam remained.

Such devastation is familiar to this country located atop a fault-line; the archipelago nation has endured too many natural disasters to – most recently, in January 2024, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake in the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture. But remembrance is the ritual whereby the Japanese make sense of their fate. In Honshu, a purpose-drawn map demarcates the numerous "disaster memorial facilities" strung out along the 500km stretch of coastline affected by The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011. Obscured from view below the railway line are cairns erected by earlier generations to warn of nature's ferocity.

"Don't build homes below this point," reads one inscription. "No matter how many years have ed, be alert for tsunami."

That volatile ocean was a sea of tranquillity as we rambled northwards from the city of Kamaishi to Namiitakaigan, a seaside hamlet four hours north of Sendai in Iwate Prefecture. Here, flowers trailed from the cottage gardens abutting Namiitakaigan Station; a cenotaph 266m uphill from the beach was looped with Japanese script: "This is where the tsunami reached."

Getty Images

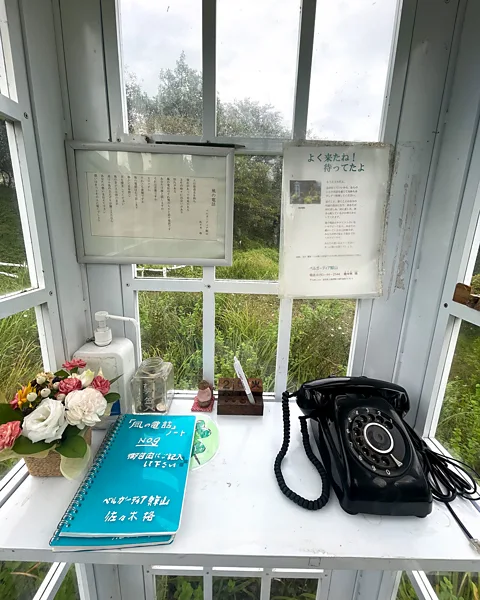

Getty ImagesWe'd been drawn here by a story: in a beautiful garden on a nearby hill stands a phone box where people commune with the dead. Before the disaster, Namiitakaigan resident Itaru Sasaki created a metaphorical connection with his recently deceased cousin by placing a disconnected telephone inside a British-style phone box. Here, he explained in a 2016 episode of This American Life, he could speak to his cousin, his thoughts "carried on the wind". As stories of Sasaki's ritual spread, those affected by the tsunami – and other tragedies – arrived to seek their own solace on "The Phone of the Wind".

RAIL JOURNEYS

Rail Journeys is a BBC Travel series that celebrates the world's most interesting train rides and inspires readers to travel overland.

Though thousands of people have trod the path to Sasaki's garden, we were its sole visitors that day. Birds flitted between frothy crepe myrtles and maple leaves slowly changing colour; it was a poignant setting in which to meditate on loss: so electric with life, so hefted with sorrow. I closed the phone box door behind me, lifted the receiver and silently communed with the loved ones I'd lost.

The mood lifted on the way back into town: we met a woman pushing a pastry cart from door to door, and bought two of her custard-filled doughnuts.

"Oishi! (Delicious!)" we said, skipping down the hill.

Second-hand memory assailed us once more on the road leading to Minshuku Takamasu, our lodging for the night: "Tsunami Inundation Section," a sign said. But proprietor Yasuko Nakamura's face was wreathed with a smile as she welcomed us in. Only the roof of her elevated ryokan was damaged by the tsunami, she communicated through gestures and a translation app and my friend's rusty Japanese.

“I was at my home in Trono [an hour’s drive inland] when it came,” she said.

Catherine Marshall

Catherine MarshallAnd though foreign guests are now rare, Nakamura was busy enough with her long-term lodgers: high school boarders, a fisherman-diver who made his living from the bay, a builder working on the reconstruction of the nearby town of Otsuchi, which we'd ed through on our way here. Half of its dwellings and most of its commercial properties were wiped out by the tsunami. The builder's efforts would help to make Otsuchi stronger, he said, as Nakamura served the fruits of that once-vengeful sea for dinner: wakame (seaweed) salad, grilled saba (mackerel), miso broth bobbing with a delectable but indeterminate ingredient.

"What is it">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });