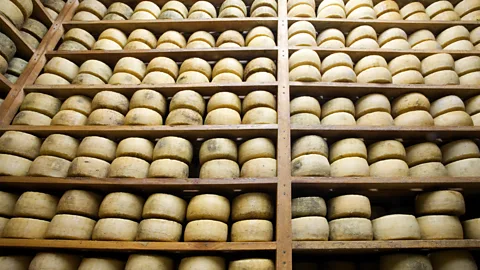

Why Italian cheesemakers buried their pecorino

seraficus/Getty Images

seraficus/Getty ImagesWhen Covid hit Italy in 2020, the pecorino industry careened towards life . But thanks to the ingenuity of several producers, the cheese is now perhaps better than ever.

Loreto Pacitti was stumped. He was desperate. The pecorino producer couldn't sell one of Italy's most famous cheeses. No one could. Covid had closed restaurants and public markets, skyrocketed production costs and curbed public spending. Worried his cheese would spoil, he did what his ancestors did hundreds of years ago.

He buried his cheese in a cave.

"During the lockdown I lost almost everything," said Pacitti, owner of La Caciosteria di Casa Lawrence in the village of Picinisco in the Lazio region. "But then because of this system [of burying cheese] I recovered everything."

Pecorino, a strong, hard, savoury, salty cheese made from sheep's milk, comes in a variety of styles, such as fresco, which is light and typically used in salads; semi-stagionato, which is aged for about 60 days and often eaten with bread or fruit; and stagionato, which is sharper, more brittle and aged for 36 months. Gennargentu di Pitzalis Bruno, a manufacturer outside Rome near the town of Bracciano, makes 26 different pecorinos.

As Rome restaurant owner Massimo Innocenti said, "Pecorino is really the final food. I always thought that if I was on a deserted island and I had pecorino, it would be perfect."

Innocente is up close and personal with Pecorino. Under the floor of his restaurant, Necci dal 1924, is a 2,000-year-old cave left over from the Roman Empire where he stores all his pecorino.

The many types of pecorino

"Pecorino" is the name given to all Italian cheeses made from ewe's milk; the word itself stems from the word pecora, meaning "sheep". However, not all pecorino is the same. Eight, high-quality versions have been given D.O.P. status by the European Union, including Pecorino Romano (originating from the Lazio region near Rome), Pecorino Toscano (from Tuscany) and Pecorino Sardo (from Sardinia). Of these, Pecorino Romano is perhaps the most popular and the oldest. And while a few remaining high-end producers still make Pecorino Romano in Lazio, much of it is now produced in Sardinia (not to be confused with Pecorino Sardo).

Pecorino Romano, a version originally hailing from the Lazio region near Rome (hence the name "Romano"), is the cheese that defines the Italian kitchen. It's lighter, drier and saltier than other pecorino varieties, and bonds so many Italian dishes such as cacio e pepe, pasta carbonara and bucatini all'amatriciana (a typical Roman dish made of pasta, pig's cheek and tomatoes). It's seasoned for up to two years and is delicious with a dab of honey and a glass of wine. And it has been around Italy for 2,000 years.

During the Roman Republic (508-27 BCE), shepherds needed to do something with their excess sheep's milk and so they made what is Pecorino Romano. The Roman Empire's renowned agricultural writer, Lucio Moderato Columella, wrote about what appeared to be Pecorino Romano in 50 CE in De Re Rustica. Turns out, Pecorino Romano was an ideal food for Roman armies as it had a lifespan longer than many soldiers. In the Middle Ages, people started adding salt to Pecorino Romano and discovered that it helped preserve the cheese. Soon, it spread beyond the Italian peninsula.

Pecorino Romano has survived the fall of the Roman Empire, earthquakes and fascism.

"Pecorino Romano is like a Roman soldier," said Rome-based food writer Rachel Alice Roddy. "It's meant to be a working cheese."

Despite its name, Pecorino Romano is sold on a large scale as it is used primarily in the home kitchen. This mass-produced version, affordable and readily available in supermarkets across Italy, not only survived Covid, it thrived. During Italy's lockdowns, families stocked up on it. In fact, sales went up during Covid, going from 26,940 tons sold in 2019 to 34,280 last year.

Artisanal pecorinos, meanwhile, nearly became another Covid victim when restaurants and public markets closed, and producers wondered what they'd do with factories full of cheese going bad fast. And so, they resorted to selling it door to door. They grew their own corn to combat the growing cost of sheep feed. And they buried it in caves to preserve it for a later date.

Fausto Caserio

Fausto CaserioPacitti said, "I tried to sell to the people door to door. I opened an online market, but it wasn't working very well. Then I changed the production scheme."

In July 2020, he made bigger cheeses so he could preserve more at one time and took them to Emilia-Romagna in central Italy where he buried them in a cave of tufa stone 4m deep.

Hundreds of years ago, people hid their food in similar caves, known as fossa. "Even the cheeses," Pacitti said. "Then they discovered the cheeses became better with longer shelf life." According to Innocenti, "In Europe, the practice of ripening cheeses in underground pits dates back to the Middle Ages and was used to protect food from the raids of occasional invaders." Over time; however, it became less common for producers to use the fossa and the practice faded.

Pacitti filled his cave and sealed it for three months, allowing the cheese to eat all the oxygen, mature and develop in flavour. His Pecorino Picinisco, for example, becomes spicy and crumbly in the mouth with hints of porcino mushrooms and chestnuts. Now it's one of his most popular sellers. The process also extends the cheese's life to 18 to 24 months instead of five to six.

"When I eat the pecorino in the fossa, I'm in a good mood because the pecorino in the fossa is very strong," said Romina, his sister and co-proprietor.

Marina Pascucci

Marina PascucciNot far away in Settefrati, Maria Pia and brother Antonio are ninth-generation shepherds. Every June, they take their sheep 17km to a plain 1,000m up. The sheep supply pecorino for their family's Agricola San Maurizio business.

However, production costs tripled on feed for the animals, electricity for their factory and gas for the tractors.

"The animals eat and don't know we had Covid," Maria said.

To combat costs, they grew their own corn. They now make 12,000 kilos a year and save €20 (about £18) per 100 kilos. To the Pias, pecorino is their lifeblood.

"It is my family food," Maria said. "Every day, we have a different picture of our work. It represents the little farmers, the identity and tradition."

At Gennargentu di Pitzalis Bruno, marketing director Silvano Secchi recalled the throes of Covid when sales and Italians' income flatlined.

Marina Pascucci

Marina Pascucci"It's difficult to find people who are willing to pay for quality," he said. "Because people have less money and can't spend money for quality cheese and so it's very difficult to sell pecorino which costs €40 (£35.50) a kilo."

Fuel during Covid went from €0.50 (£0.44) a litre to €1.30 (£1.15). Overall expenses increased 60%. They upped their prices 10% and sales dropped 25%.

"We organised some other things," Secchi said. "Otherwise, it would've been 80%."

Secchi and owner, Bruno Pitzalis, started online sales, shipped cheese and sold home to home. To attract business, they gave away free ricotta, made from leftover sheep's milk that's recooked after the production of other cheeses. ARSIAL, the regional association for agricultural development, gave them €10,000 (£8,900) for a website.

Helping his recovery was one of his best clients, Massimo Innocenti, the owner of restaurant Necci dal 1924 and its 2,000-year-old cave.

In 2006, Innocenti bought the restaurant, which has occupied a corner in the gritty Pigneto neighbourhood of south-east Rome since 1924. However, it wasn't until July 2020, when he decided to build a wine cellar, that he discovered there was an open space under the floor.

Marina Pascucci

Marina Pascucci"We didn't dig," he said. "We just lifted some tiles. Just 10cm down were just concrete and iron bars. They closed it like a tomb."

What they found was a sprawling cave that dates to the Roman Empire. The Ancient Romans used it to store pozzolana, a volcanic sand used in making cement. Innocenti spent eight months turning it into a cheese cellar and started creating and storing different pecorinos. Since then, he has been using different varieties of pecorino on cheese plates and in dishes at the restaurant.

His kitchen maestro, Shahin Gazi, who first learned to cook seafood in his mom's kitchen in Bangladesh, came to Necci in 2010.

"I'm a pecorino fan," said Gazi. "It's good to pair with sharp and aggressive ingredients. It's why it's perfect for Roman cuisine because Roman cuisine is the homeland of sharp tastes and aggressive tastes."

Take Necci's Jewish-style artichoke in Pecorino Romano cream and paprika croutons. The artichoke is deep fried on a bed of thick pecorino sauce. Even for someone who doesn't like artichokes(such as this writer), the Pecorino made it more than palatable.

Marina Pascucci

Marina Pascucci"Artichoke is the most difficult thing to pair in the kitchen," Gazi said. "It's an eternal fight with all the ingredients. They fight together. Pecorino is a great match because both are strong and powerful. From this fight between two ingredients is born a great friendship."

Then there is the pici di grano saraceno (buckwheat pasta with pumpkin, pig's cheek and chestnuts in a Pecorino Romano sauce). "All the ingredients in this pasta are very strong and aggressive flavours," Gazi said. "We have the sweetness of the pumpkin, and we have the saltiness of the guanciale (pig's cheek)."

The highlight of the menu may be the pan-fried prawn salad served in a Pecorino Romano basket with leeks, ginger and balsamic vinegar reduction. After eating the balsamic-coated shrimp, you eat the basket like a giant pecorino cracker.

"Every pecorino has a different taste," said Agathe Jaubourg, Innocenti's wife and co-owner. "It touches many different aspects of the taste. It can be sweet; it can be spicy. It's very interesting with wine. When you have wine, the taste changes."

But after 2,000 years, some things never change, such as the longevity of pecorino, which even Covid couldn't end.

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

---

more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.