South America’s stunning ‘marble cathedral’

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonDeep in the remote reaches of Patagonia, a shimmering glacial lake holds a spectacular geological marvel.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonWhatever the time of year, visitors to Chile’s wild southern fringes would be well advised to pack for all four seasons. Menacing clouds can intensify or dissipate in minutes, and fierce winds ensure an ever-shifting forecast.

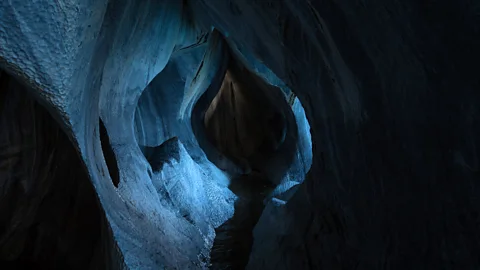

But on this morning in the early austral spring, as dawn breaks over the shore of Lago General Carrera, the water is calm. The lake, a glacier-fed giant that spans the border with Argentina and is one of the largest in South America, is host to one of Patagonia’s most spectacular natural wonders.

Boasting sculpted pillars, vaulted ceilings and ornate, textured walls, this unique geological formation on the western edge of the lake is known as the ‘marble cathedral’ by locals.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonWhen you arrive at the caves, there’s a stillness, a clearness, a synthesis of colours that you fall in love with,” said visitor Hans Claussen.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonThe cathedral lies just metres from the shore, but the steep, forested slopes behind it mean the only way to get up close is by boat.

In the morning, the main chamber is in shadow, and light entering the cavern is reflected off the surface of the lake. The deep turquoise colour of the water, caused by glacial silt, casts the grey and white surfaces in an ethereal blue hue, while the unique stone contours conjure up stunning compositions. The sound of waves gently lapping against the walls echoes around the cavern, accompanied by drops of water steadily falling from the marble ceiling.

Depending on the season, the level of the lake can vary significantly. During the summer months, meltwater from the surrounding mountains can cause the lake to rise by around 1m. In winter, the waters recede to reveal parts of the caves that are usually below the surface.

The colours on show are more than a mere trick of the light. Narrow filaments of brown stone line the interior walls, and veins of yellow course from the ceiling.

“When a rock undergoes metamorphosis, new minerals are formed,” explained geologist Francisco Hervé. The sections of white marble are the purest, composed almost entirely of calcium carbonate, while the other shades of rock owe their colour to various impurities.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonSmall boats and kayaks are able to inch their way into the cathedral’s two main chambers, allowing visitors to appreciate the intricately textured surfaces up close. But the lake’s marble wonders don’t end there. The Capillas de Marmol natural sanctuary, which encomes a coastal area of 50 hectares, is lined with dozens of other caves and formations, which have formed over millennia. “We know that this region was covered by glaciers until 10,000 or 15,000 years ago,” Hervé said. “After the glaciers retreated, the lake was created, and that was when the process of sculpting the chapels began.”

According to Hervé, the stone found in and around the caverns probably formed closer to the equator around 300 million years ago before slowly grinding south via continental drift. “They were formed at temperatures of around 300C to 400C, between 10 and 15km underground,” he said. The rock began its epic journey as sedimentary limestone, before the intense heat and pressure needed for metamorphosis transformed it into marble.

Compared to the hundreds of millions of years it took for the marble to reach its current location, the erosion of the caverns has happened in the blink of an eye, due in large part to the chemical properties of the stone itself. “These calcareous rocks, which are composed mainly of calcium carbonate, are among the most soluble that exist,” Hervé explained.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonPeople have thought the photos I took in the ‘chapels’ were actually modern artwork. When I told them that these were marble caves, they were astounded!” said Chelsea Dietsche, an American visitor based in Chile.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonPedro Contreras moved to Puerto Río Tranquilo on the lake’s western shore as a young man and never left. Thirty years ago, he was one of the first to take intrepid tourists to visit the caves, but the last decade has seen visitor numbers to the tiny town grow rapidly. “We used to be just three or four boats. Now there are 50 boats going back and forth to the cathedral,” he said. “Everyone in Puerto Río Tranquilo works in tourism. They used to raise livestock.”

Interest in the caverns may have transformed Puerto Río Tranquilo, but the town has retained much of its frontier charm. Wood smoke puffs silently out of every chimney, warming the little cottages throughout the harsh Patagonian winters. In the newly renovated town square, a sculpture depicts the region’s first settlers navigating the lake by dinghy.

While some locals are nostalgic for the hardier times of old, Contreras says that on balance, the modern world has improved life here. “Things have changed quite a lot, but for the better,” he itted. “Patagonia is more comfortable now.”

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonBefore the tourists came the road. Vast swathes of Patagonia were practically cut off from the rest of Chile until the 1970s, when General Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship put thousands of soldiers to work building a highway through the Aysén region. Laying the road required a Herculean effort: beginning in Puerto Montt, the route es fjords, mountains, glaciers and forests, eventually winding more than 1,200km south to the town of Villa O’Higgins on the Argentinean border.

The road, which is most commonly known as the Carretera Austral (‘Southern Highway’, in English), opened Patagonia to the rest of Chile. Despite barely being more than a gravel track at certain points, it remains the single artery connecting the north of the country with the Aysén region.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonAs well as being a lifeline for remote communities, the Carretera has become legendary among travellers. The route takes in many of Patagonia’s natural wonders, including Cerro Castillo, a mountain instantly recognisable for its turret-like crags, which forms the centrepoint of a multi-day trek to rival more famous hikes in the Torres del Paine National Park further south.

Claussen, a visitor from the bustling Chilean capital, Santiago, has been to the region several times and says he will never tire of it. “Aysén is my favourite place in the world,” he explained. “Time es more slowly, life is simpler, the immensity and beauty of the landscapes make you feel small and privileged at the same time. You’re at the end of the world, where mankind has still made little impact.”

Large stretches of the Carretera are lined with pristine wilderness, and in 2017, the Chilean government signed an agreement with Tompkins Conservation to create more than four million hectares of new national parks in the surrounding area, ensuring it remains undeveloped.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonThe scenery in the Aysén region is spellbinding. You have to travel long distances to get anywhere, but there is always something new to look at around the corner – an amazing view, a beautiful forest, the wildlife,” said Pippa Mitchell, a visitor from New Zealand.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonEfforts to preserve Patagonia for future generations are beginning to extend to the marble caves, and Contreras says local tour operators are trying to minimise their impact. “Before, you could get off [the boat] and take photos, walk around. But not anymore,” he explained.

Hervé, meanwhile, hopes the natural beauty of the caverns can highlight the importance of preserving other geological formations across the country. “In Chile, we’re really clear about the concept of biodiversity,” he said. “But not at all about geodiversity.”

He argues that the benefits of conserving sites like the cathedral go well beyond their obvious aesthetic appeal. Over the Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, erupting volcanoes, advancing and receding glaciers and undulating sea levels have all left their mark on the surrounding environment. According to Hervé, there is a wealth of geological information carved into the stone chapels’ foundations that could provide us with invaluable knowledge about how the Earth’s temperature fluctuated in the past. “Things like climate change, for example, worry us all as a society,” he said. “How can we know if these rocks couldn’t give us some clues about the processes which happened in the past, why they occurred, how we could avoid them happening again in the future?”

World of Wonder is a BBC Travel series exploring some of the most awe-inspiring natural phenomena and manmade marvels around the globe.

(Video, images and text by Tom Garmeson; additional drone footage by Javier Cañete)