Why Scotland loves haggis

Graham Franks/Alamy

Graham Franks/AlamyWhether you are partial to haggis or not, the rituals that surround its consumption on Burns Night each year are a glorious dip into rich Caledonian history and culture.

Long before today's chefs began celebrating the idea of 'nose-to-tail eating', Scots were putting it into practice in what is now their national dish. Haggis provided warming sustenance in wild settings far removed from any gourmet restaurant. Or, as beloved 18th-Century Scottish poet Robert Burns put it in his famous poem Address To A Haggis: ‘But mark the Rustic, haggis-fed,/The trembling earth resounds his tread.’

Scotland's iconic dish began as a nod to the necessities of harder times, when using as much as possible of a slain animal was essential. But while some cuts of meat could be salted or dried for preservation if not eaten immediately, internal organs were far more perishable. Haggis made use of these by putting them into a convenient natural casing – the animal's stomach – which could then be cooked on the spot.

Traditionally, haggis takes the chopped or minced 'pluck' of a sheep (heart, liver and lungs) and mixes it with coarse oatmeal, suet, spices (nutmeg, cinnamon and coriander are common), salt, pepper and stock. This mixture is then stuffed into a casing – today sometimes synthetic rather than a stomach, and no longer eaten as part of the dish – to be simmered for two to three hours.

The result when placed on a plate looks a little like a balloon bulging full of dark meat. It gives off a subtle, savoury aroma that soars wonderfully when the casing is cut open to reveal the hot meat within.

Graham Franks/Alamy

Graham Franks/AlamyYou may also be interested in:

• How a Uruguayan town changed how we eat

In its early days, haggis served as a hearty meal for those on the move across Scotland: whisky-makers transporting liquid gold across majestic Highland hills; merchants shipping wares across the choppy sea to the islands of Orkney and the Hebrides; drovers' taking their beasts from heather-clad moors to feed hungry cities.

Though drovers and whisky-makers no longer roam modern-day Scotland, haggis is still eaten year-round – you can even buy it in tins or from fast food shops. But the one day Scots turn en masse to their beloved dish, serving it up with a huge helping of ritual traditions, is Burns Night – a meal held every year to celebrate the life and works of Scotland's national poet on 25 January, his birth date back in 1759.

Though haggis is Scotland's national dish, similar foods – offal quickly cooked inside an animal's stomach – have existed since ancient times. Perhaps the first reference is in Homer's epic poem The Odyssey, where a age speaks of ‘a man before a great blazing fire turning swiftly this way and that a stomach full of fat and blood, very eager to have it roasted quickly’.

Other similar dishes include chireta from the Spanish Pyrenees, the Romanian dish drob (traditionally eaten at Easter) and Sweden’s pölsa. Recipes have even been found for haggis-like dishes in England as far back as the 15th Century.

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesWith growing Scottish nationalism focussing attention on traditional foods like haggis, contemporary chefs are coming up with interesting variations on the classic dish. Scotland's abundance of deer underpins a surge in venison haggis, while the country's significant Indian population has inspired haggis pakora, a fried fritter where the offal can be spiced with ginger, cumin seeds, coriander seeds, turmeric and garam marsala.

Scottish chef Paul Wedgwood, who runs an eponymous restaurant in Edinburgh, has been one of the boldest pioneers in new takes on haggis. On a 2016 trip to Peru that coincided with Burns Night, he made a haggis using a common meat in that part of the world: guinea pig.

“The traditional recipe is always the start point for creating the different types of haggis, but I also take into where in the world I am and try to include local herbs and spices,” Wedgwood explained.

Three quirky facts about haggis

1. You can now buy haggis-flavoured crisps and ice cream.

2. Hall’s of Scotland made the world’s largest haggis in 2014, weighing 1,010kg – as much as a small car.

3. Haggis hurling is an actual sport. In June 2011, Lorne Coltart set the current world record when he hurled a haggis an impressive 66m.

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty ImagesBut to experience the delights of haggis in the most evocative and memorable way, a Burns Night dinner provides the perfect template. Here, haggis plays the starring role in the memorable meal that includes colourful rituals as well as traditional accompaniments.

The first Burns Night was celebrated in 1801, though held on 21 July when a group of his friends came together at Burns’ childhood home in Ayrshire to celebrate his life and achievements on the fifth anniversary of the poet's death, rather than the birthday we celebrate today. These annual haggis suppers now range from informal gatherings of friends and family to large formal feasts.

A traditional menu will start with soup, and the two commonly served on Burns Night are cock-a-leekie (using chicken and leek) or cullen skink (like a rich smoked haddock chowder). The haggis is the centrepiece of the evening, traditionally served with ‘neeps and tatties’ – swede and potato – which can be simply boiled or mashed into a smooth puree that pairs perfectly with the rough oaty texture of the haggis.

As well as the distinctive food, there will be whisky. Cooks can make a whisky-based sauce to serve with the haggis, as well as serving guests glasses of whisky to accompany the meal. It is up to the guests whether they want to sip the whisky or pour some of it over the haggis on their plate for a bit of extra traditional Scottish kick.

A sweet dessert is not necessary on Burns Night, but one traditional option is cranachan, a tasty concoction of raspberries, oatmeal and cream plus a dash of Scottish heather honey – and whisky.

Burns is thought to have written his famous Address To A Haggis in 1786 prior to a dinner at the house of an Edinburgh merchant friend when haggis was being served as a special treat, having by then moved from portable travelling food to celebratory Scottish dish.

For Burns, haggis was a food fully worthy of rising from its humble roots. He wrote with brilliant colour and conviction in his famous Address about how it is finer fare than many a fancier plate, belittling any who would choose ‘French ragout’ or ‘fricassee’, or dare ‘looks down wi' sneering, scornfu' view/On sic a dinner’.

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty ImagesAs well as the fire and brilliance of his words, Burns is loved for how his poetry embodies two key elements of the Scottish spirit – an awareness of the hardship experienced by many people in his time, alongside an appreciation of the pleasures of life that can provide a balance. This is a man who knew about hard labour in his work as a ploughman, as well the intellectual skills of poetry.

Burns wrote with equal insight of the universal ions and pain of love in famous works like My Luve is like a Red Red Rose and Ae Fond Kiss, And Then We Sever, but also of inequality in A Man’s A Man For A’ That – a searing proclamation of shared humanity whatever one's social status. These poems are often chosen by guests to recite during the various ‘Entertainments’ that punctuate the feasting, when diners can show their knowledge and iration for Burns.

But the poetic centrepiece of Burns Night is the host reciting his Address To A Haggis. The reciter should have a knife ready when saying the line ‘His knife see rustic Labour dight’. When the moment comes, he or she should slice the haggis open along its length, making sure that some of the delicious meat within spills out for the assembled diners to see: what Burns describes as ‘trenching your gushing entrails’.

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

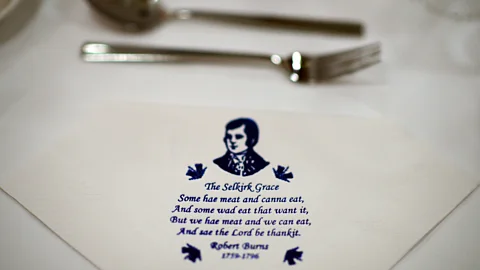

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty ImagesBurns Night celebrates other aspects of Scotland's history and culture, as well as its national dish. The feast traditionally begins, for example, with a bagpiper piping in the haggis as it is borne to the table. There are also readings of classic texts such as the Selkirk Grace in gratitude for the food (‘…we hae meat and we can eat’).

There is also a chance for personal testaments of the widespread love of Burns, most famously in the important toast known as The Immortal Memory. This is made by the host, and should reflect their own personal reasons for iring the poet, as well as explaining why his poems still have relevance to modern times. Common themes include praising how Burns combined manual labour with intellectual genius, his sympathy for the world's oppressed, or iration for how his work preserves the language and heritage of Scotland.

The host closes the proceedings by inviting guests to stand and belt out a rousing rendition of Auld Lang Syne, based on a Burns' poem and recognised by Guinness Book of World Records as one of the most frequently sung songs in the English language.

Let us in and sing the praises of haggis.

The Ritual of Eating is a BBC Travel series that explores interesting culinary rituals and food etiquette around the world.

more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

{"image":{"pid":""}}