The medieval marvel few people know

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerEngland’s 500-year-old angel roofs are striking – and all but unknown. Michael Rimmer’s photographs provide a rare chance to encounter their beauty up close.

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerThink of medieval England’s finest gems, and castles probably come to mind first. But the country has another type of treasure that few people know about: angel roofs. Built between 1395 and the English Reformation of the mid-1500s, these roofs are decorated with intricately carved wooden angels. Only 170 survive today. Because so little of the art from England’s medieval churches survived the Reformation, that still makes these cherubim “the largest surviving body of major English medieval wood sculpture”, writes photographer and expert Michael Rimmer in his book The Angel Roofs of East Anglia: Unseen Masterpieces of the Middle Ages.

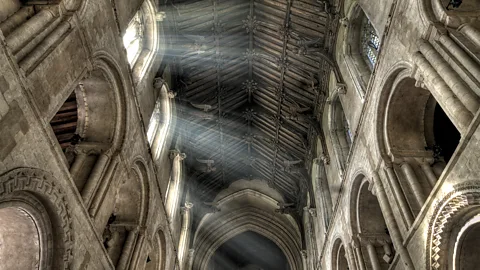

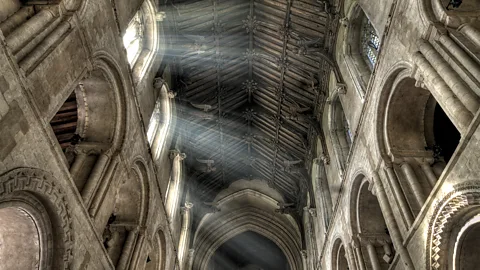

But the roofs remain seen by few; even those who visit the churches don’t always catch their details. “Distance and lighting make it hard to appreciate the detail of angel roofs with the naked eye, or even with binoculars. Were they as accessible and visible as, say, the Renaissance paintings in Italian churches, I think the best of them would be just as highly celebrated,” Rimmer writes. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

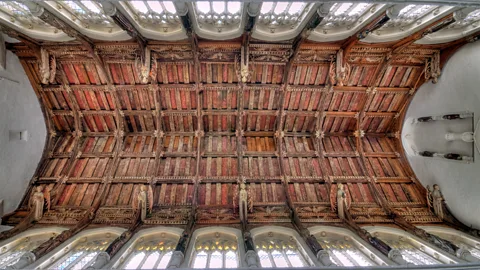

The roof that started it all, Westminster Hall – now in London’s Houses of Parliament – once was called “the single greatest work of art of the whole of the European Middle Ages” by historian John Harvey. Built at the end of the 14th Century by King Richard II’s master carpenter, it was the world’s first major hammerbeam roof. In this type of construction, beams step out and up, each one ing the next layer – allowing them to themselves without the need for ing columns or flying buttresses. But because the roof’s 13 pairs of oak hammerbeams each are carved with angels, the Westminster Hall roof also is considered the world’s first angel roof. (Credit: Alamy)

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerThe angels at Westminster Hall aren’t just decorative. Projecting out from the walls, they vertical hammer posts and help hold up the entire roof structure, which is no mean feat: the roof’s oak alone weighs some 600 tons. With each angel carrying the King’s arms, the figures also enforce Richard II’s claim to absolute power; as Rimmer notes, “he was the first king to insist on the title ‘Royal Majesty’ and to require courtiers to bend the knee”.

Within a couple of decades, similar angel roofs were springing up across England, particularly in East Anglia. That may be because the Westminster Hall architect moved from that project to one in Norfolk, spreading the idea (and his expertise) among others in the region, which includes Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerAt the church of St Peter and St Paul in Swaffham, Norfolk, there are no fewer than 192 angels. It is extraordinarily lucky that any of them have survived. Carved when this roof was built in the mid-14th Century, they would have been prime targets for zealots when England broke with the Roman Catholic Church during the English Reformation. In that period, reformers attacked – and destroyed – all forms of medieval religious imagery, including the countless numbers of paintings, statues and other decorations that once made England’s medieval churches bright and colourful. It’s thought that more than 90% of religious imagery from England’s Middle Ages was lost by the mid-17th Century. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

“The English Reformation was not just a religious revolution. It was an artistic holocaust,” says Rimmer.

At the church of St Mary in Woolpit, Suffolk, nearly all the 66 angels decorating its hammerbeam roof were destroyed. They were replaced by restorations.

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerAside from unlucky churches like St Mary in Woolpit, because they were so high up and difficult to access – not to mention because they ed the roofs themselves – most of the angels were left alone.

But that didn’t mean there weren’t attempts to destroy them. Despite orders that the Suffolk church of the Holy Trinity in Blythburgh, shown here, destroy its 20 roof angels, they somehow survived – even with much of their paint intact. The church’s stained glass did not fare as well and was mostly destroyed.

As a result, the roof angels today aren’t just pretty decorations. When most of England’s 9,000 medieval churches today lack the art, stained glass and statues they once would have contained, the cherubim are among the few remaining, tantalising glimpses of what England’s medieval churches would have looked like. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerThe roof of the church of All Saints in Necton, Norfolk, also escaped the English Reformation’s iconoclasts. Today, not only the cherubim but even the wood beams themselves retain their 15th-Century colours. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerPart of the reason angel roofs go mostly unnoticed is that it’s hard to appreciate any of their details. Not only are the roofs high above our heads, making them uncomfortable (and difficult) to see, but the light in the churches is often low, making it hard to pick out their decorations. “This is where photography has a particular advantage,” Rimmer notes – a camera can both zoom in, and, unlike the human eye, use a longer exposure to brighten up the details. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

The church of St Peter in Upwell, Norfolk, however, has a rare feature: a gallery that lets visitors get a closer view of the angels. From there, you can see every detail of the carvings that were made as early as 1400, right down to the intricate curls (and cobwebs). Each of the carvers who worked on the angels – many of whose names have been lost – had their own style, and their figurines can be picked out across various churches. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

Michael Rimmer

Michael RimmerOne of the finest places to ire angel roofs is Norwich, which lies about 100 miles northeast of London. England’s second-largest city in the 15th Century, Norwich has no fewer than five angel roofs. St Peter Mancroft, which dates to between 1430 and 1455, is one of them. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)

Michael Rimmer

Michael Rimmer“It is strange how many otherwise irable s of medieval building either fail to mention the roofs at all, or describe them in such a dubious and uncertain way that their is almost unintelligible,” wrote the authors of the 1917 book English Church Woodwork. The roofs have continued to be all but ignored by academics, art historians and travellers – something Rimmer wants to rectify by bringing medieval marvels like this one, 570-year-old Wymondham Abbey in Norfolk, into the light. (Credit: Michael Rimmer)