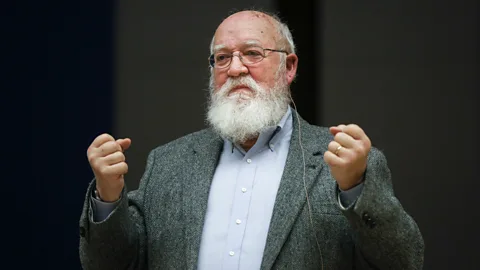

Daniel Dennett: 'Why civilisation is more fragile than we realised'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBefore his recent death, the influential philosopher Daniel Dennett spoke to the BBC about his lifelong quest to understand human experience – and why he saw new dangers from AI.

The philosopher Daniel Dennett, who died at the age of 82 on 19 April, was among the sharpest and most prophetic minds of the last half-century. Throughout his life, he dared to tackle some of the biggest questions about the human mind and consciousness. His career saw him publish over a dozen books, make major contributions to fields ranging from cognitive science and philosophy of mind to evolutionary theory, and become an ardent advocate for rationality and scepticism.

In December 2023, I spoke to him for several hours about his recent memoir, I've Been Thinking, as well as his life and work. He was still ionately engaged with the questions of truth, cognition and technological possibility that first fascinated him as a doctoral student at Oxford in the 1960s – and still willing to pick a fight in the service of rigorous thought.

In particular, our conversation focused on the grave risks posed by artificial intelligence. His warning was not of a takeover by some superintelligence, but of a threat he believed that nonetheless could be existential for civilisation, rooted in the vulnerabilities of human nature.

"If we turn this wonderful technology we have for knowledge into a weapon for disinformation," he told me, "we are in deep trouble." Why? "Because we won't know what we know, and we won't know who to trust, and we won't know whether we're informed or misinformed. We may become either paranoid and hyper-sceptical, or just apathetic and unmoved. Both of those are very dangerous avenues. And they're upon us."

Science fiction philosophy

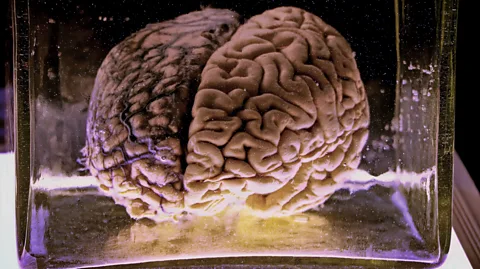

To understand Dennett's argument about AI – and what made him such a deep and original thinker – it's worth looking back to one his most unusual academic papers. In 1978, he published Where Am I?, which took the form of a science fiction short story featuring his own brain in a vat.

"Several years ago," the story begins, "I was approached by Pentagon officials who asked me to volunteer for a highly dangerous and secret mission." Thanks to an accident during a classified research project, a drilling device bearing an atomic warhead had got stuck a mile underground, beneath Tulsa, Oklahoma. They needed him to help retrieve it. More precisely, they needed his body. In order to avoid the neuron-damaging radiation being emitted by the device (plausibility isn't a necessary feature of philosophical science fiction), his brain would be surgically removed and hooked up by radio transceivers to his body. He could then remotely control it without risking exposure.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe question behind Dennett's delightful fantasy was this: assuming the procedure succeeded, and his brain continued to control his body and receive inputs via its sensory organs, where would Daniel Dennett be? In the story, he imagines his body walking into the room where his brain floats within a reinforced vat, then sitting down and looking at it.

The scene was recreated for television in a 1988 documentary by Dutch director Piet Hoenderdos – in which Dennett played himself (with gusto). It's surely one of the only cases of an academic paper receiving such an adaptation. "Well, here I am sitting on a folding chair, staring through a piece of plate glass at my own brain," the flabbergasted Dennett declares. "But wait… shouldn't I have thought, 'Here I am, suspended in a bubbling fluid, being stared at by my own eyes'">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });