The secret lives of Neanderthal children

Kennis & Kennis Reconstruction

Kennis & Kennis ReconstructionAmong the growing collection of Neanderthal remains to be discovered are fossilised bones belonging to children. Now we are gaining unprecedented insights into what being a young Neanderthal was like.

In any normal summer, Spain's famous Playa de la Castilla – a perfect 20km (12 mile) long stretch of sand backed by the Doñana nature reserve and close to the resort of Matalascañas, Huelva – would have been covered by the footprints of visiting tourists. But in June 2020 with international flights banned due to Covid-19, the beach was uncharacteristically quiet. Two biologists – María Dolores Cobo and Ana Mateos – who were strolling along the peaceful beach, nonetheless found many footprints. These, however, were made by a very different kind of visitor.

As savage storms and then powerful spring tides earlier in the year had lashed Spain's south-west coast, huge waves scoured away the sand at the base of 20m (65ft) dunes, revealing an enormous area of rock covering some 6,000 sq m (1.5 acres). Its surface was pocked with indentations which the pair of biologists recognised as footprints: a jumble of hooves, claws and paws preserved in the rock. But when the two women looked closer, among the criss-crossing animal tracks were other prints that looked startlingly human. What's more, their position at the bottom of the cliff layers meant they had to have been left in the distant past.

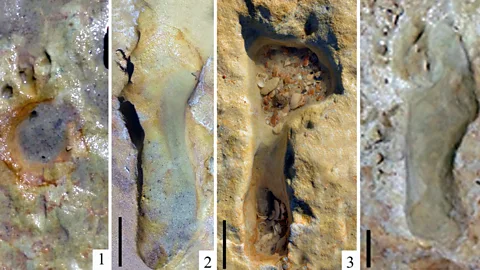

Later dating showed the footprint surface formed around 80-120,000 years ago, meaning they can only have been left by Neanderthals, walking barefoot along the margins of a salty marsh or lagoon. What they were doing, and where they were going, we can only guess at, but among the 87 prints found were some much smaller than the others. This was a group, and some of them were children.

Eduardo Mayoral et al/Scientific Reports

Eduardo Mayoral et al/Scientific ReportsUntil relatively recently the lives of Neanderthal children have been largely mysterious. But a revolution in archaeology over the past two or three decades has started to uncover intimate details about even the smallest of them.

At Matalascañas, researchers used drones and photogrammetry technology –stitching together high resolution images – to record and create a digital model of the Neanderthal tracks before they were once more engulfed by sand within a few days of their discovery.

Measurements of the prints revealed adults were present, but the majority – about 71% – were teenagers and youngsters as little as six years old. What were they doing? There are also animal prints, but they're largely in the wettest areas, while the Neanderthal tracks were walking up to and away from the water's edge, rather than along the shore. Some even appear to have wading in a short distance, and the researchers speculate that they may have been stalking animals or fish. Those in the shallows include youngsters, and it's possible they were there watching and helping to forage, while perhaps also paddling and splashing, mixing play with learning as children do today.

Thanks to a multiplicity of scientific methods like this (along with some good fortune), archaeologists are now gaining an unprecedented portrait of Neanderthals, from head to toe. And one of the biggest shifts in understanding involves the children of these close relatives of our own species.

To explore this further, let's begin at the beginning: how did they grow up?

Despite smaller, more delicate bones, researchers have a relatively large number of Neanderthal children's remains to study. If you lined them up, you'd see a range of ages: awkward teenagers to school-age kids, all the way back through to toddlers and even tiny newborns.

By assessing their skeletons, it initially seemed that even from their first days under the Sun, infant Neanderthals' development was remarkably similar to that of our own babies. Yet anatomical features only visible with immense magnification have shown more subtle differences.

Known as "perikymata", tiny lines form inside teeth every few days, from the first stage of growth. Using microscopes and even synchrotrons – some of the most powerful scanners on Earth – researchers can count these lines, and cross-reference them with other parts of the skeleton. This confirmed that Neanderthal children's teeth were forming slightly faster, albeit by only a day or so, than those of living humans. Some Neanderthals, however, apparently lost their milk teeth a year or more early.

You might also like:

However, Neanderthals were individuals. Most of the skeleton of a boy who lived in northern Spain around 50,000 years ago points to him having been about nine when he died, but the perikymata in his back teeth and some of his bones look less developed. Perhaps he was just one of those children who would have suddenly shot up in his teens, but it is a good reminder that, just like school kids in the playground busily comparing whose teeth are missing or wobbling, Neanderthals also grew up at varying rates.

Whatever the foibles between individuals, if you set up a super time-lapse recording the growth of two newborns, one Neanderthal, the other from anywhere on the planet today, you'd see how the particular form of their bodies became ever more different over time.

Perry van Munster/Alamy

Perry van Munster/AlamyWhile likely covered in cute downy fluff like our babies, the Neanderthal's head would already feel more elongated. And you couldn't tickle them under the chin so easily either, because they lacked the bony nobbles already visible on our infants' ultrasound portraits.

Intriguingly, modelling of skull shape suggests that even if Neanderthals' heads grew marginally faster and were differently shaped, their brains didn't develop differently, meaning their babies probably hit the magical milestones of smiling, crawling and walking at roughly comparable times. Had those two time-lapse youngsters met, they'd have been able to play, and probably giggle, together.

A child's first word is one of the most eagerly anticipated stages in their early life, but did Neanderthals speak? A range of anatomical evidence points to the conclusion that vocal communication of some sort was key to everyday Neanderthal life. By reconstructing the vocal tract thanks to rarely preserved hyoid bones, a delicate part inside the throat, it seems Neanderthals were able to make broadly similar range of vowel sounds used by humans today.

Moreover, despite some dissimilarity in the internal shape of their ears, it turns out that their hearing was still tuned into almost exactly the same frequencies as ours: the sounds of speech. While their first "words", in the sense of sounds with commonly understood meanings, were probably just as simple as those of our children, modelling of their hearing also implies Neanderthals could detect soft consonants – think of breathy "h", "t" and "s" sounds. These are important in separating out syllables, and most useful in face-to-face speech, strongly suggesting that after coos and squawks, baby babbles would have turned into rather more complicated vocal constructions. This means that, if we could eavesdrop at a Neanderthal hearth, we would recognise a kind of language.

One of the things Neanderthal little ones may have first begun speaking about was milk. As fellow mammals, their infants were breastfed from birth, and remarkably we can see direct evidence of this thanks to chemical markers in their developing teeth. Based on that data, youngsters began eating other foods from as early as four months old, to over seven months old, which is in line with current trends.

As with many traditional and hunter-gatherer societies, breastfeeding continued well into toddlerhood, and in one case potentially up to four years of age. But for one youngster whose remains were found in Belgium, the chemical marker stops so abruptly at just over a year old, that something untoward may well have happened to the mother.

Even if most Neanderthal children were weaned much more gradually, this might still have been a difficult time for health. Another dental feature records disruptions in tooth enamel deposits, often associated with serious illness, infection or poor nutrition. While the causes in individual Neanderthals aren't possible to determine, the disruptions are especially common in children around 3–5 years of age, perhaps relating to when breastfeeding stops: milk likely provides ongoing immune system even in older children, so its removal might have boosted chances of illness.

Yet overall, recent work on disrupted enamel samples suggests that Neanderthal children did not experience significantly greater stress effects than early Homo sapiens populations.

cc-by-sa-3.0 Guerin Nicolas

cc-by-sa-3.0 Guerin NicolasPoor health was, however, a fact of existence. Many Neanderthal remains are witnesses to a variety of illnesses and infections, some of which must have led to painful and challenging lives. A older man from La Ferrassie, suffered not only a fractured collarbone – actually quite common today – but also a break in the top of his thighbone, inside the hip t. This is far more serious, probably resulting from twisting his leg during a heavy fall, and must have drastically altered his mobility. Yet while he probably never walked the same again after the fall, he clearly survived for decades.

Another famously battered survivor is known as Shanidar 1, from a cave in Iraqi Kurdistan. Probably partially sighted after a crushing injury to the left side of his face, his right arm also has multiple fractures and is entirely missing its lower part. On top of that he had a malformed right shoulder blade, plus an unusually small and likely chronically infected collarbone. What exactly happened to Shanidar 1 isn't clear – including whether it was one or more separate, awful events – but once again, this trauma didn't kill him. Instead, despite the arm bone shrivelling, he adapted and continued to use the stump, even becoming old enough to develop arthritis which would have added a limp to his ailments.

Accumulating ill health over the course of a lifetime is perhaps not surprising, but the youngest Neanderthals were apparently sometimes also at risk from injury. The Devil's Tower boy, found in 1926 in Gibraltar, died at only around five years old, possibly from skull fractures. But he had already suffered another serious incident earlier in life: as a toddler, his jaw was fractured. It's impossible to say how these injuries happened, but clearly, Neanderthal childhood could be dangerous.

Yet not all Neanderthal bones bear visible trauma, and the overall number of apparent injuries aren't that different to those seen in hunter-gatherers living in similarly tough conditions today. Moreover, any notion that they had a low life expectancy is hard to .

There are many remains of children and young adults, but also a fair number of Neanderthals appear to have died at a relatively ripe age – past 50 and perhaps older. One, known as the "Old Man" of La Chapelle-aux-Saints, , had just a single injury – a long-healed broken rib – but still, he didn't have it easy. Along with bony ear growths probably causing some hearing loss, he had arthritis from a long life filled with exertion. Perhaps most striking, he had also lost about half his teeth and had suffered terrible dental abscesses. Found in 1908, his skeleton was used for an unfairly primitive reconstruction, showing a stooped, aggressive, and highly ape-like figure.

While that vision of the Old Man was hugely influential in creating persistent negative perceptions of Neanderthals, it doesn't match modern understanding of their biology. In peak condition they were strong, highly athletic and certainly nothing like a missing link to gorillas or chimpanzees. They were fully upright, and while slightly shorter and with a slight difference in gait, biomechanical modelling suggests they walked just as efficiently as living people. Certainly, Neanderthals moved around an awful lot: not only does the archaeological record indicate sites were only used for a few weeks at a time, but their own legs show signs of highly developed muscles. For the children, this would have meant an upbringing where "home" was not only found in caves or rockshelters, but entire landscapes, known intimately.

The most rarely preserved traces of Neanderthals movements, however, are to be found in their footprints. In the cave of Theopetra, near Thessaly in central Greece, a scatter of diminutive prints can be found. Left there some time before 128,000 years ago they appear to have come from two different individuals. One was so small it was probably made by a child just 2-4 years old, while the other was larger and may have been wearing foot-coverings, but together they show quite young Neanderthals were active within chambers away from the "main" living zone near the cave mouth.

Another subterranean site in the Vârtop Cave, Romania, has footprints, this time of an adolescent. Apparently alone, they stepped into a puddle of "moonmilk" – a squishy calcium carbonate solution – which later hardened. Strangely, the imprint is the only trace Neanderthals were ever in Vârtop. Was this a teenager out exploring in the darkness?

Other Neanderthal footprints are in the open air, and remarkably, the majority once again seem to be youngsters. The most ancient come from gloopy volcanic ash deposits on the Roccamonfiore volcano, Italy. After ash and massive mudflows spewed out by an eruption some 350,000 years ago had cooled, at least three Neanderthals variously picked their way down the slopes, one zig-zagging, another slipping and occasionally putting down a hand for balance. Based on calculated height from the print size, they were around 1.35m (4.4ft) tall, most likely making them teenagers, just like at Vârtop.

Hercules Milas/Alamy

Hercules Milas/AlamyBut where were this little adolescent gang going? It's quite possible they had witnessed the likely terrifying eruption, and their direction suggests they were leaving the area. But on the other hand, tracing the prints back upslope reveals they came from a flat ledge area speckled for at least 50m (160ft) with animal tracks: perhaps creatures also caught in the disaster were skirting the volcano. Vulnerable in the sticky stuff, searching for escape or food, they would have presented easy prey for the Neanderthals. Perhaps that young Neanderthal slid while carrying a furry load back to a group waiting elsewhere.

The recent prints found at Matalascañas in Spain, however, are extremely special as they may provide the only evidence so far that even small Neanderthal children were part of everyday foraging. After all, they had to learn somehow. Yet at places without footprints, we're forced to guess who was there. Take the 330,000-year-old German lakeshore hunting site of Schöningen, where skillfully butchered carcasses of between 20-50 horses together with eight finely carved spears testify to this as a well-known hunting spot, used many times. Although impossible to be sure, we might image youngsters crouching wide-eyed along the shore, close enough to watch the slaughter, hear the thudding of spears, smell the horse-sweat: learning to be Neanderthals.

* Rebecca Wragg Sykes is an Honorary Fellow in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, and author of the award-winning Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art.

The picture of the footprints at Matalascañas are used under a Creative Commons license from the paper by Eduardo Mayoral, et al, (2021) Tracking late Pleistocene Neandertals on the Iberian coast, Scientific Reports.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.