The switch that saved a Moon mission from disaster

Nasa

NasaJust a few months after the triumph of Apollo 11, Nasa sent another mission to the lunar surface. But it came chillingly close to disaster.

In November 1969, just four months after men first set foot on the Moon, Nasa was ready to do it again. Basking in the success of Apollo 11, the agency decided that Apollo 12’s mission to the Ocean of Storms would be even more ambitious.

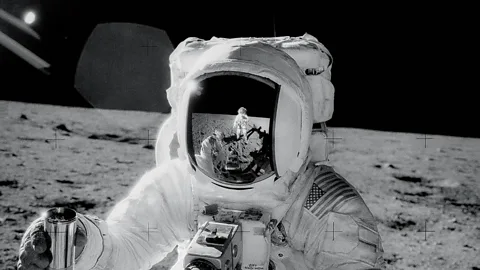

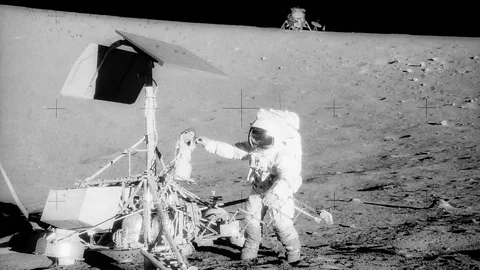

Unlike Neil Armstrong, who had been forced to overshoot his planned landing site because it was strewn with boulders, Apollo 12 Commander Pete Conrad was aiming for a precision touchdown, within moonwalking distance of an unmanned Surveyor probe. Conrad and landing module pilot, Al Bean, would then spend longer on the surface – with two excursions planned – while beaming back the first colour television from the Moon.

On 14 November, Conrad, Bean and Command Module Pilot Dick Gordon settled into their couches at the top of the 111-metre-high Saturn 5 rocket at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Meanwhile, in mission control Houston, flight director Gerry Griffin took his seat behind his console – his first time leading a mission.

You might also like:

At the launchpad, the ground was wet from storms that recently ed through the area and the sky is overcast. But with the rocket and crew ready to go, and US President Richard Nixon watching (for the first time) from the VIP stands, all systems were green for launch.

At 11.22, the giant white rocket slowly lifted off the pad and accelerated into the clouds.

“This baby’s really going,” shouts Conrad to his crewmates as the launcher cleared the tower and Houston takes over control. “It’s a lovely lift-off.”

Then, 36 seconds into the flight, Conrad sees a flash. All the fuel cells supplying power to the capsule fell offline and the entire alarm lit up.

Nasa

Nasa“What the hell was that,” Conrad exclaims.

A few seconds later, the capsule navigation system cut out. Almost every electrical system in the spacecraft has failed.

“Okay, we just lost the platform, gang,” Conrad reports to mission control. “We had everything in the world drop out.”

With the spacecraft and crew seemingly in peril, mission control needed to act fast.

“We didn’t know what had happened at first,” Griffin later tells me.

It’s only later that he discovered the rocket had been hit by two lightning strikes.

“We generated our own lightning,” says Griffin. “Ionisation of the extremely hot exhaust from the Saturn 5 created a ground.” In effect, the rocket became a giant conductive rod connecting the electrically charged clouds with the Earth below.

Although the spacecraft appeared to be in serious trouble, the rocket beneath carried on following its planned trajectory. This was thanks to the design of the Saturn 5 guidance computer. Arranged in a ring around the upper section of the rocket, it was unaffected by the double lightning strike.

Back in mission control, decisions had to be made. “I thought we were going to have to abort,” Griffin says. “But I keep looking at the plot [on the screen] and we never get off track.”

Nasa

Nasa“Then this young man from a little college in Oklahoma named John Aaron, who was at that point around 25, I'd guess, made a call,” says Griffin.

“He says: ‘Tell him to try SCE to Aux’ – I had never heard of the switch and I said, ‘What?’”

Aaron repeated the instruction. Griffin turned to the Capcom (capsule communicator) responsible for talking to the crew, Jerry Carr.

“So, I tell him to say. ‘Try ‘SCE to Aux’ and Carr said ‘What?’…at that point, Aaron said ‘Try SCE to auxiliary’, so that’s what he transmitted to the crew.”

But Conrad had never heard of the switch either. “Try FCE to Auxiliary?” he says to the ground, and then to his crewmates: “What the hell is that?”

Fortunately, Bean knew the switch – it was right in front of him. SCE stands for Signal Conditioning Equipment, the system that processed spacecraft sensor data for transmission to the ground.

The capsule began to come back online. The crew reset the electrical systems, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

“I listen back to my own voice tapes on the flight director loop,” says Griffin, “and I notice I got about an octave and a half higher and then I calmed down a little bit back to normal.”

“God darn Almighty!” exclaimed Gordon at the time. “Wasn't that something, babe!”

Nasa

Nasa“We got into orbit, fixed everything up, tested everything we could,” says Griffin. “Everything looked okay and so I said, ‘Let's go to the Moon.’”

Four days later, Conrad and Bean landed on the lunar surface just metres from their intended target – the Surveyor 3 probe.

“You made a beautiful landing,” says Bean as they completed their post-landing checklist. Conrad was happy to share the credit with Houston: “You guys did outstanding targeting! I'll tell you, that thing was right down the middle – beautiful!”

“Man,” says Conrad, “I can't wait to get outside.”

With fears that after the success of Apollo 11, the American public – the ultimate funders of the programme – were already losing interest in going to the Moon. Nasa hoped the first live colour TV from the surface would keep them riveted to their screens.

“Within the United States there was less interest than there was during the summer for Apollo 11,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, Apollo Curator at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. “But around the world there was still quite a lot of enthusiasm for Apollo 12.”

American TV networks CBS and NBC both carried the mission live. In the era before cable and satellite, this meant the mission reached tens of millions. But although TV was a priority for Nasa public relations, the astronauts received little training in how to operate the camera.

As Conrad descended the ladder onto the lunar surface, he pulled a handle to release the door of an equipment storage bay on the outside of the lander. The video camera was clamped inside and, as the locker swings open, viewers saw the first blurry colour pictures of Conrad’s legs as he moved into shot.

Nasa

Nasa“You're coming into the picture now, Pete,” reports the Capcom, Ed Gibson, in Houston.

The third man on the Moon – a relatively short man – prepared for his own giant leap. “Whoopie!” says Conrad, “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me.”

A few minutes later, Bean ed him on the surface and the astronauts enjoyed a few minutes of acclimatising to the alien environment and marvelling at how close they have landed to their target.

Bean removed the shoebox-sized camera from the equipment bay to mount it on a tripod, so viewers could watch the Moonwalk. But as Bean positions the camera, he accidentally pointed it towards the Sun. Most of the picture went black, with a bright indistinct white patch at the top of the screen.

Despite the best efforts of the astronauts and engineers in mission control, no amount of adjustment could get the picture back. It seemed the image sensors were irreparably damaged.

Fortunately, the TV networks had a back-up plan. While continuing to carry the live voices of the astronauts, CBS switched to a studio where two actors dressed in spacesuits simulate the Moonwalk.

NBC, meanwhile, commissioned puppeteer Bil Baird to build astronaut marionettes. Baird (who would train Muppet creator Jim Henson) operated the puppets from an overhead gantry above a simulated lunar landscape. Despite having the word “simulation” on the screen, Baird is quoted as saying that many viewers never realised it wasn’t real.

The effect of the Apollo 12 camera failure, combined with these bizarre attempts to mock-up a Moonwalk, would later fuel conspiracy theories that men never really walked on the Moon. But for Nasa public affairs there was a more immediate impact.

Nasa

NasaWatching actors or puppets wandering around in a studio pretending to be on the Moon did little for TV audience ratings. And attention was shifting to other global events.

“Apollo 12 wasn't the only major headline at that time,” says Muir-Harmony. “The mission occurred right around the time that news of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam broke.” This horrific murder of hundreds of civilians was a defining moment of the Vietnam War.

In scientific and engineering , Apollo 12 was a near-flawless mission. With its pinpoint landing and two Moonwalks, the astronauts carried out dozens of experiments, deploying instruments that would continue to send back data for almost a decade.

The TV companies, however, used the camera failure as an excuse to abandon in-depth live coverage. When Apollo 13 launched in April 1970, none of the networks carried the live broadcasts as the crew made on their way to the Moon.

Landing on the Moon was no longer news. A disaster in space on the other hand would soon pull-in the viewers…

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.