Apollo in 50 numbers: Oddities

Nasa/Getty Images

Nasa/Getty ImagesNot all of the equipment carried into space was cutting edge and expensive. Some of the more humble odds and ends even prevented disaster.

18: Apollo spacecraft names

The second American in space, Gus Grissom, named his Mercury capsule Liberty Bell 7 – representing a patriotic symbol of American independence and Nasa’s first seven astronauts.

Grissom’s 15-minute sub-orbital flight in July 1961 went perfectly but, shortly after splashdown, explosive bolts on the hatch blew prematurely. As the spacecraft filled with water, the astronaut scrambled out, nearly drowning before the recovery helicopter could reach him.

When Grissom took command of the first two-man Gemini mission in 1965, he chose the name Molly Brown, after The Unsinkable Molly Brown, a popular Broadway Show. Nasa preferred to call the spacecraft Gemini 3 but when Grissom suggested naming it Titanic instead, they relented.

You might also like:

We will never know what Grissom planned to call his first Apollo spacecraft, Apollo 1. The astronaut died in a horrific launch pad fire in January 1967, along with his companions Roger Chaffee and Ed White.

For the first two manned Apollo flights – Apollos 7 and 8 – it looked like the era of naming spacecraft had come to an end. “We were called Apollo 7 which is kind of nice,” says astronaut Walt Cunningham. “Seven was a nice number.

“I tried to design our patch to be like the phoenix recovering from a fire but they didn't like that,” he says. “They didn't even really want us to name the spacecraft, so we didn't have a named spacecraft.”

But, with Apollo 9, Houston had a problem. From now on, the missions would have two spacecraft – a command module and lander – and mission control needed call signs to distinguish between the two. Names were back. Some would become as well known as the astronauts.

Many of the 18 spacecraft call signs are sombre and patriotic. Apollo 11 had the Eagle lander and the Columbia mothership, named after Jules Verne’s fictional Columbiad spaceship. Apollo 14’s command module was Kitty Hawk, the site of the Wright Brothers’ first flight. The last men on the Moon landed in Challenger – indicative of the challenges of the future.

Nasa

NasaBut some call signs tapped into 60s popular culture – Apollo 10 had Snoopy and Charlie Brown, from the Peanuts cartoon. And the Apollo 16 command module was called Casper, after the friendly cartoon ghost.

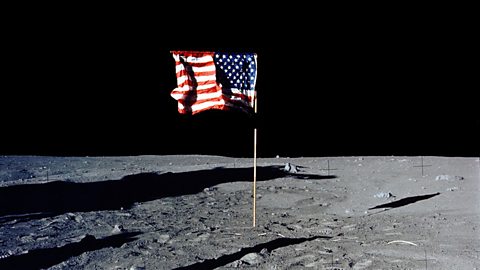

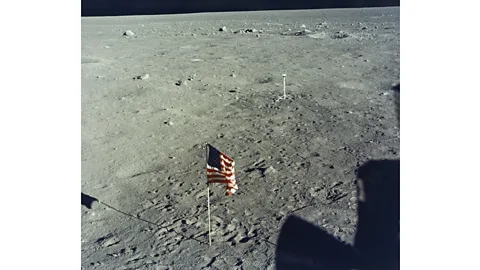

5.50: Cost of the flags flown to the Moon, in US dollars

The image of astronauts planting an American flag on the Moon is one of the most enduring of the Apollo programme. But it almost didn’t happen. Instead Nasa managers discussed the idea of planting a United Nations flag, concerned that a US flag would imply America was taking possession of the Moon.

Eventually, after much discussion and only three months before the first Moon landing, engineers started work on a lunar flag assembly. They ordered a $5.50 3ft by 5ft nylon flag from a government catalogue (about $38/£30.60 in 2019) and $75 ($523/£421) of metal tubing. The pole was designed to be pushed into the lunar soil and had a telescopic rail attached horizontally at the top, so the flag would hang like a curtain.

The question then arose about where to stow the flag on the lunar lander. Storage inside was already ed for, so engineers designed a special casing attached to the lander ladder. It had to be fire-proof to protect it from the heat of the engine.

The flag was only installed on the lander – along with a commemorative plaque – on the morning of launch, while the lander was already at the top of the rocket.

Although Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had practiced deploying the flag during simulations, when it came to the real thing, they struggled to push it into the lunar soil. They also had trouble extending the horizontal rod, which gave the flag a ripple effect – one of the sources of lunar landing conspiracy theories.

As they took off from the lunar surface, Aldrin says he spotted the flag falling over – a result of the engine blast.

Nasa/Getty Images

Nasa/Getty ImagesThanks to pictures captured by Nasa’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) satellite, we have a good idea how the Apollo flags have fared over the last 50 years. The LRO images appear to confirm that the Apollo 11 flag has fallen but the flags from the other Apollo missions are still standing. However, after decades in the harsh sunlight, all of them are likely to be bleached white.

25: Length of duct tape rolls carried to the Moon, in feet

If there’s one saviour time and again of American space missions over the past 50 years, it’s a roll of duct tape. During Apollo missions, it was used for everything from taping down switches and attaching equipment inside the spacecraft, to fixing a tear on a spacesuit and, during Apollo 17, a fender on the lunar rover.

During Apollo 13, duct tape helps save the lives of Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise. Fifty-six hours into the mission, an explosion knocked out the fuel cells in the command module and the crew took refuge in the lunar lander.

But there was a design flaw: the canisters designed to scrub carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the lunar lander are round and the canisters in the command module are square. And there aren’t enough round canisters to keep the astronauts alive.

To survive, the crew are going to have to fit the square canisters of the command module into the round holes of the lander. Engineers in mission control work round the clock using only materials astronauts have in the spacecraft to come up with a fix. And duct tape is used to hold everything together.

{"image":{"pid”:”p07gz0ht"}}

“So, we developed a way to use the command module cartridges by taping a hose so it would go through our cartridge into the lunar module and scrub out the CO2,” says John Whalen, an engineer for the spacecraft environmental system.

“It took them a while to tape up but thank goodness it worked – and that's the way we saved everybody.”

You can read more about space hacks here.

398: Stamped envelopes taken to the Moon (Apollo 15)

Every astronaut has taken mementoes with them into space – some for personal or sentimental reasons, some for family or friends and some for profit. By the time of Apollo 15, it had become an accepted practice for astronauts to carry stamped and postmarked envelopes – known as covers – to the Moon.

Throughout the space programme, Nasa management turned a blind eye to any arrangements astronauts made. They never asked what the crews carried with them among their small allocation of personal effects in their Personal Preference Kits. It was an informal policy the agency would come to regret.

Like other astronauts before them, the Apollo 15 crew – Dave Scott, Al Worden and Jim Irwin – agreed to take some postal covers to the Moon, via an intermediary, on behalf of a stamp dealer. As the astronauts understood it, the deal was that the stamps wouldn’t be sold until they had left the space programme. Money raised would go into savings s for their families.

In his autobiography, Worden would later describe it as “without a doubt, the worst mistake I ever made.”

Scott, carried the covers to the Moon in a sealed package in his spacesuit. But within weeks of splashdown – and without the astronauts’ permission – some of the items went on sale. The crew returned the profits and told the dealer to keep the stamps. But it was too late. Nasa wanted to make an example of them.

The fallout from the affair led to recriminations, a Senate investigation and ended the crews’ astronaut careers. For a while, the controversy overshadowed what had been an outstanding scientific mission.

Public Domain

Public DomainOther items crews took to the Moon included flags, medallions and – also during Apollo 15 – a miniature statue representing fallen astronauts. Apollo 16 astronaut Charlie Duke left a photo of his family on the lunar surface.

Today, objects flown to the Moon can fetch tens of thousands of pounds at auction.

500: Seeds flown to the Moon

Before he became an astronaut, Stuart Roosa had an even more dangerous job. He was a smoke jumper – a highly trained firefighter who would parachute into remote forest areas to tackle wildfires.

When he was assigned as command module pilot for Apollo 14, in January 1971, the US Forest Service once again asked for his help. Scientists wanted to see whether seeds would be affected by weightlessness.

Roosa agreed to take 500 seeds from American redwood, pine, sycamore, fir and gum trees. He carried them in his personal kit the 238,855 miles to the Moon, where he orbited 34 times, before returning to Earth.

The seeds survived the journey but during a decontamination process (part of the procedure to protect the Earth from possible moonbugs), the capsule containing the seeds burst open. Scientists feared many would be lost or damaged.

Once they were planted, however, most of the flown seeds grew into healthy saplings, with no discernible difference between those flown to the Moon and regular seeds on Earth.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTrees grown from the seeds have become known as Moon Trees. They have been planted around the world, including at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and in the White House garden.

A Moon sycamore overlooks Roosa's grave at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The trees and second generation Moon Trees, grown from cuttings carried by the astronaut, will continue to provide a living legacy of the Apollo missions long after all the astronauts have died.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.