Rediscovering India’s forgotten masterpieces

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionPigeonholing great works of art as the property of the East India Company has meant they’ve been ignored for centuries. But a new exhibition is giving due recognition to artists who deserve to be as well-known as Michelangelo, writes Rahul Verma.

They were simply labelled ‘Company Painting’ and ‘Company School’; but some artworks assigned to a niche bureaucratic category are now being recognised as masterpieces. Paintings commissioned by patrons of the East India Company during the late 18th and early 19th Centuries are currently on show in an exhibition at the Wallace Collection in London.

Forgotten Masters – Indian Painting for the East India Company focuses on artists who were previously neglected. According to its curator, historian William Dalrymple, they should be celebrated as “major artists of the greatest capabilities”.

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

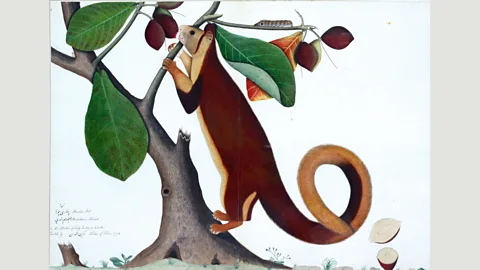

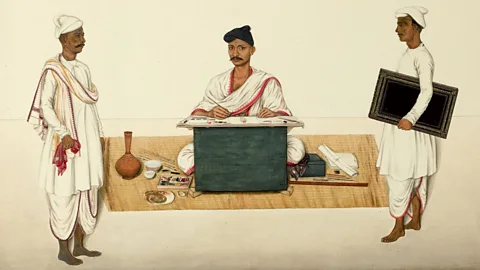

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionThe exhibition presents a dizzying range of exquisite paintings reflecting colonialism’s insatiable thirst to catalogue, document and chronicle. They feature Indian wildlife (animals, flora, fauna), people and buildings, for European botanists, zoologists, anthropologists and architects to study; today, the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew and Edinburgh are home to thousands of paintings and illustrations from this era.

Botanical beauty

Despite being more than 200 years old, many of the wildlife works are wonderfully vivid and leap from the high-grade European paper imported by enthusiasts such as French Company man, Claude Martin, who shipped 17,000 pages of watercolour paper for natural history pictures. Shaikh Zain ud-Din’s Indian Roller on Sandalwood Branch (1779) is stunning, with the shading of the bird’s inky blue and turquoise plumage, and the delicate ripples of its nape and auricular, embodying both European natural history styles and Mughal painting traditions.

Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark. Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark. Minneapolis Institute of ArtIt seems remarkable that work of such brilliance has been neglected – but their labelling means they’ve been caught in limbo, as Dalrymple tells BBC Culture. “They’re toxic to both India and Britain – to India they’re not Indian enough, they reek of colonialism, and for Britain there’s an embarrassment around Empire. After the collapse of Empire, the British put this thing in a trunk in the attic and forgot about it.

“You don’t think of the Sistine Chapel as a work of papal art, it’s by Michelangelo and Raphael [among others], but somehow because the artists are Indian and their names have never been known, the work has been pigeonholed as ‘Company School’ art. The key thing has been to remove the Company from the centre of the story and foreground the genius of the Indian artists, it’s a tragedy that Ghulam Ali Khan, Shaikh Zain ud-Din and Yellapah of Vellore are names people simply don’t know,” he continues.

Dr Yuthika Sharma, who teaches and researches Indian and South Asian Art at the University of Edinburgh and has written a chapter (The Late Mughal Master Artists of Delhi and Agra) in the exhibition catalogue, agrees Indian painters have been disregarded because of the reductive ‘Company Painting’ label, although that’s now changing.

Private collection

Private collection“[The term] ‘Company Painting’ has been used for decades to refer to works painted for colonial (mostly East India Company) patrons, implicating a top-down relationship between the patron and the painter, where the latter served the imagination of colonial masters,” she tells BBC Culture. “This view is now being actively revised in the scholarship, arguing for the recognition of painters as agents of resistance and change: the decolonisation of painting and of the art historical discourse in Indian art is a real and present challenge.”

South Indian artist Yellapah of Vellore seems like a person who would not be impressed by the erasure of his work – his quietly mesmerising self-portrait, Yellapah of Vellore (1832-1835), in oyster shell paint, sees the artist confidently holding the gaze of the viewer, and is full of beautifully rendered details, whether the shading of his hands or the fine hair of his moustache. More than anything, the selfie oozes dignity and assurance in his craft, as well as personality, agency, and perhaps defiance towards his paymasters – in 1806, the Vellore Rebellion saw Indian sepoys mutiny against British commanders.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Victoria and Albert Museum, LondonIndeed, the paintings of people in particular reveal plenty – not only about intimate, interpersonal relations, but how they evolve and adapt as the balance of power is skewed towards a marauding colonial enterprise backed by military might, plundering and ransacking in plain sight. Early in the exhibition we see John Wombwell, a Yorkshire ant, embracing local customs and style, sitting on a rug, enjoying a hookah dressed in Mughal finery – Portrait of John Wombwell Smoking A Hookah (1790) – in the north Indian city of Lucknow, a cultural and artistic hub.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, ParisAs Dalrymple explains, in the early part of the Company Painting era (1770 to 1840) there was a more equal footing and sense of cultural exchange between India’s Mughal rulers and East India Company officers. “At this stage, the British aren’t in control, they’re on the rise, the Company is becoming more powerful but we’re not in the Raj, there’s a Mughal Emperor in Delhi. It’s a very interesting half-lit world that’s not colonial but not entirely Mughal, it’s a transition between the two and cultural transfer is an important part of the story – the wills of Company officials from this time show that more than one third of British men in India left all their possessions to Indian wives or Anglo-Indian children.”

Shaikh Zain ud-Din’s natural history works – Dalrymple says they make English painter George Stubbs “look like a child daubing with watercolours” – commissioned by Sir Elijah Impey, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, and Lady Impey, have seen the Patna-born artist rightly lauded. Yet it’s his painting, The Impey Children in their Nursery (1780), depicting an everyday scene of the Impey’s three children being tended to, with an ayah (nanny) breastfeeding an Impey baby, that stands out.

Scenes of intimacy

“It’s something so incredibly intimate and it’s amazing that it’s been portrayed. In a way that’s the strangeness of the Company period, although it’s deeply exploitative and all about looting and asset stripping, it’s collaborative – the Company is being paid for by Indian finances, its battles are being fought by Indian sepoys paid by the Company, and Indian wet nurses are suckling the children,” says Dalrymple.

Private collection

Private collection“The Company succeeded because India was so divided and it allowed the Company – which was never more than 2000 white men in India – to conquer this vast, rich and incredibly sophisticated culture, using Indian finance and soldiers. You’re quite right to zero in on that suckling as a symbol, in a sense of India giving the milk, that provided the sustenance to the company,” he continues.

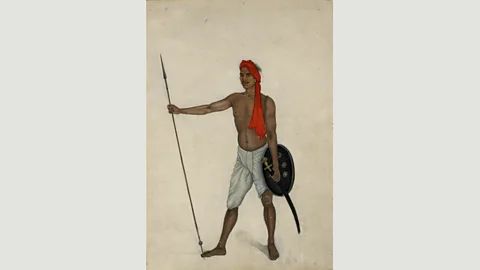

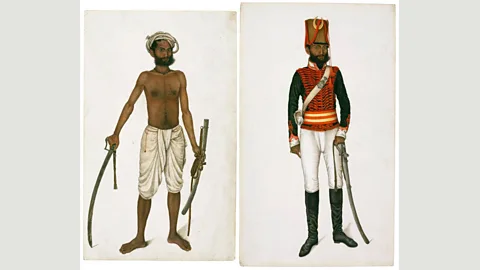

Early in the exhibition we see a Yorkshireman in Mughal clothing, and towards the end there’s a rough-and-ready Indian man, Kala, also playing dress up and sporting European military attire – Kala in the Uniform of Skinner’s Horse (1815-1816). Kala, who became close friends with his employer, Company officer William Fraser, looks resplendent in a Napoleon-style jacket, Jodhpur boots and a sash sporting the crest of the Fraser family, yet he retains a strong sense of self, with a moon – signifying the Hindu deity Shiva – adorning his headwear.

David Collection, Copenhagen

David Collection, CopenhagenThis painting and Kala’s story is an example of why revisiting and re-evaluating so-called ‘Company Painting’ can prove so valuable, as Sharma explains. “Kala is the subaltern that speaks volumes through his portrait. Someone like him is regularly effaced in the archive but here he is given his own space and agency as an individual and a soldier. Men like Kala were part of the larger body of irregular recruits that ed Company officers, without whom Company expeditions and day-to-day work of ‘settling’ the countryside would have been impossible to implement.”

A triptych of paintings of nautch girls (dancing girls) in early 19th-Century Delhi offer a rare and brief glimpse of Indian women. “Women hardly appear in the painted archive except as idealised portraits as noblewomen,” says Sharma. “From that perspective, the frank and candid portraits of the nautch girls painted by émigré Patna-based artists Hulas Lal and Lalji are a real asset – portraits of the women capture their confident personas and a sense of resilience especially in the way the women appear to be returning the gaze to the onlooker.”

According to Sharma, “The nautch girls in Delhi were musicians and performers who were an integral part of courtly culture. They were highly skilled and erudite women who were held in esteem within royal circles and were often part of the royal household. Sadly, they also suffered from the fallout of the Company’s takeover of courtly affairs and, with their livelihoods threatened, had to resort to a sort of traveling troupe lifestyle.”

British Library

British LibraryForgotten Masters is also the familiar story of painters and artists struggling to earn a living – as Mughal rulers were choked off by the ruthless Company, they turned to wealthy British patrons and enthusiasts attached to the Company and became attuned to their European tastes. By the last section of the exhibition, Indian painters are largely painting in a European style – for example, Sita Ram’s The Great Gun of Agra Beneath the Shah Burj (1815) is reminiscent of John Constable’s bucolic rural English watercolours.

For Dalrymple, much of the work on display in the exhibition is the final stand of Indian painting, the last hurrah of a 2000-year-old tradition – before the ruptures of Imperial colonialism with The Raj, and photography, arrived. This is his “private ion”; Yellapah of Vellore’s Sepoys of Madras (1830) is the cover of Dalrymple’s latest book, The Anarchy: the Relentless Rise of the East Indian Company, and the enthusiasm and pride with which he talks about celebrating the artists and their work in a major exhibition is palpable.

“The reality is that it’s spectacular art by great artists,” he says. “One of the pleasures of this exhibition has been giving agency and honour, or ‘bhav’ as we say in Hindi, to major artists who should be as well-known as Goya and Turner.”

Forgotten Masters – Indian Painting for the East India Company is at the Wallace Collection, London, until 19 April 2020.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.