What the earliest fragments of English reveal

British Library Board

British Library BoardThe earliest fragments of English reveal how interconnected Europe has been for centuries. As an exhibition in London brings together treasures from Anglo-Saxon England, Cameron Laux traces a history of the language through 10 objects and manuscripts – including a burial urn, a buckle with bling, and the first letter in English.

The interconnectedness of Europe has a long history, as we’re reminded when we explore the roots of the English language – roots that stretch back to the 5th Century. Anglo-Saxon England “was connected to the world beyond its shores through a lively exchange of books, goods, ideas,” argues the Medieval historian Mary Wellesley, describing a new exhibition at the British Library in London – Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War – that charts the genesis of England.

“Something like 80% of all surviving Old English verse survives in four physical books… for the first time in recorded history they are all together [in this exhibition],” she tells BBC Culture. “The period that is represented by Old English is about 600 years, which is like between us and back to Chaucer… imagine if there were only four physical books that survived from that period, what would that say about our literature?”

What we understand as English has its roots in 5th-Century and Denmark, from where the Anglian, Saxon and Jute tribes came. As the Roman legions withdrew around 410AD, so the Saxon war bands (what Rome called ‘the barbarians’) landed and an era of migration from the Continent and the formation of Anglo-Saxon England began. The word “English” derives from the homeland of the Angles, the Anglian peninsula in . Early English was written in runes, combinations of vertical and diagonal lines that lent themselves to being carved into wood and were used by other closely related Germanic languages, such as Old Norse, Old Saxon and Old High German.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum“The earliest fragments of the English language are likely to be a group of runic inscriptions on three 5th-Century cremation urns from Spong Hill in Norfolk,” Wellesley has written. “The inscriptions simply read alu, which probably means ‘ale’. Perhaps the early speakers of Old English longed for ale in death as well as life.”

The exhibition gathers together an array of documents, books and archaeological evidence to form a dense picture of the Anglo-Saxon period, including a burial urn with runic inscriptions in early English from Loveden Hill, Lincolnshire, England.

Anglo-Saxons cremated their dead and interred their remains in earthenware vessels. About 20 objects with runic inscriptions from before 650AD are known from England, making this vessel – which seems to feature a woman’s name and the word for tomb – one of the earliest examples of English.

British Library Board

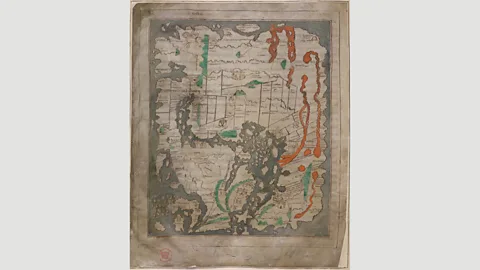

British Library BoardThe exhibition also includes a charming 11th-Century English map of the world, which gives us an insight into Anglo-Saxon identity. Britain and Ireland are squeezed into the bottom left-hand corner. (The two main population centres in England, London and Winchester, are noted.) The Mediterranean Sea is at the centre of the world’s land mass, with Rome prominent near the bottom on the left (‘Ro’ and then ‘ma’, with towers in between); across the water, Jerusalem is also prominent. Africa looms large on the upper right (follow the orange line up from the Nile delta), and India is the roughly triangular mass at the top centre.

This worldview was inherited from the Romans, who regarded Britain as being on the far edge of the world, but remained tied to the ‘centre’ by the Christian religion. Throughout the Anglo-Saxon era, which ended with the Norman Conquest in 1066, there was religious (and with it, intellectual) traffic across Europe.

Venerable Bede, an English monk and historian, noted in the early 8th Century that Britain was inhabited by four peoples who used five languages: the Picts (who remain shadowy); the Scots (whose language became Gaelic); the Britons (whose language became Welsh, Cornish, and Breton); and the Anglo-Saxons (who used a form of English). The fifth language was the Latin of the church, which eventually provided an alphabet to replace runes. On top of all of this, the Viking invasion of Britain began in the early 8th Century, adding Danish culture to the mix.

It is important to that the formation of English was influenced by a huge range of ethnic and geographical forces. The emerging ‘England’ of this period was a melting pot.

For example, we owe our English names for the days of the week, Tuesday to Friday, to the pagan religion that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them to Britain (Saturday, Sunday and Monday derive from the Greco-Roman tradition). Equally, the name of the Christian festival Easter is linked by Bede to ‘Eostre’, who seems to have been a pagan goddess. Woden, the most important pagan god, to whom we owe the word Wednesday, was also claimed as the ancestor of Anglo-Saxon royal lines. (The similarity to the name of the Norse god Odin is no accident.)

British Library Board

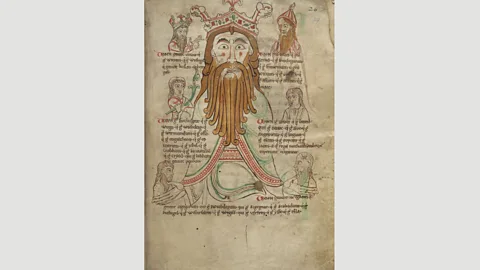

British Library BoardEven Alfred the Great, an extremely pious Christian, claimed to be a descendant of Woden. The image here is a copy from a 12th-Century manuscript; it shows Woden at the centre of the kingly lines of (clockwise from top right) Wessex, Bernicia, Deira, Mercia and Kent.

Another object in the exhibition is something of a mystery. Made of gold, rock crystal and enamel, it dates from the late 9th Century, and the inscription around the outer edge says “Alfred ordered me to be made”; from the context, scholars have concluded that this refers to Alfred the Great.

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Ashmolean Museum, University of OxfordWhat is known as the Alfred Jewel contains an empty socket, suggesting it could have been designed as a reading pointer, or æstel. If so, this object, and others like it, indicate the importance of literacy under Alfred’s reign – and especially literacy in English, which Alfred knew he needed to promote to help constitute a ‘united kingdom’ of England.

“King Alfred was very educated and clearly loved reading,” says Wellesley. “[He felt] there had been a terrible decline in learning in England, and in the more peaceful final four years of his reign he instituted a programme to promote the vernacular. It’s a wily political move, because he’s the first king to use the phrase ‘king of the English’.” In the Anglo-Saxon period, English was “very much a vernacular, a lesser language; not the language of the educated elite” – which was Latin.

According to Wellesley, Alfred had translations made of books that were “‘most needful for men to know’; these include Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Augustine’s Soliloquies, Boethius’s Consolations of Philosophy and others”. She argues that “he juxtaposes the concepts of wealth and wisdom… he is also [with æstels like the Alfred Jewel] kind of bribing the bishops to whom he sends these works”.

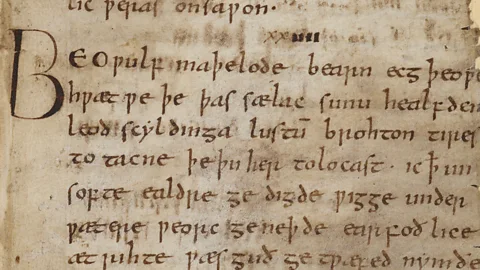

The most famous Anglo-Saxon literary text is also included in the exhibition. Set in Scandinavia, Beowulf concerns a hero’s epic encounters with, and slaying of, monsters such as the man-thing Grendel and a dragon.

British Library Board

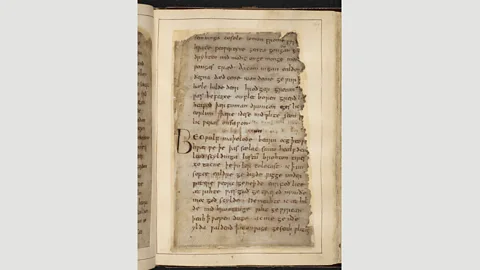

British Library BoardThe copy we have (the only existing manuscript of Beowulf), which was scorched by fire in the 18th Century, is thought to date from around the end of the 10th Century. Yet the tale was probably much older than that and likely existed as part of an oral tradition of story-telling.

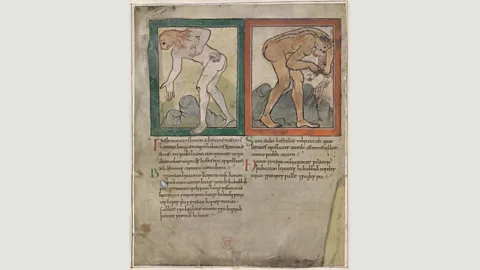

The manuscript was included in a larger collection that attests to the fascination of the period with remote places and exotic monsters. A lurid 11th-Century manuscript commonly called “Marvels of the East” (a page of which is reproduced here) catalogues (in both Latin and English) weird creatures purportedly found in the ‘Far East’.

British Library Board

British Library BoardThese include people with lions’ manes who sweat blood and people with legs 12ft (3.6m) long who capture and eat anyone ing. The manuscript of Beowulf, meanwhile, describes Grendel crunching on the bones of warriors. It’s literature that offers visually arresting images to readers more used to hearing stories being told.

The Sutton Hoo belt buckle, from an early 7th-Century burial mound in Suffolk, England, is primarily made of gold and weighs over 400g (14oz), but beyond the bling, its intricacy speaks to the surprising sophistication of early Anglo-Saxon culture – and how that fed into the development of the English language.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe surface is covered in the zoomorphic interlace which can be seen elsewhere in designs of the period, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels (also in the British Library collection): apparently it is possible to puzzle out 13 snakes, birds and beasts of various sorts tangled together in the web.

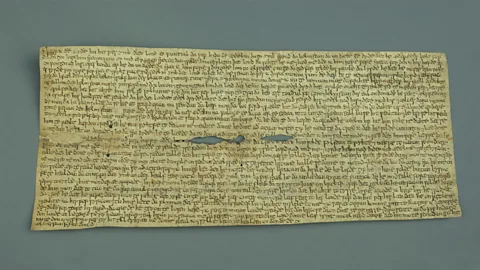

In 920, Ordlaf, a regional official in Wiltshire, England, wrote to King Edward the Elder. This, the Fonthill Letter, is the earliest surviving letter in the English language. (Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, was thought to have been “glorious in the power of his rule”. He was neglected by historians until recently and is now thought to be one of England’s great kings.)

Reproduced courtesy of the Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral

Reproduced courtesy of the Chapter, Canterbury CathedralThe letter is about what is in essence a convoluted legal dispute. Like many of the most important documents of this period, it survived for centuries through a combination of accident and neglect: it ended up in the archives of the Cathedral Church at Canterbury, where in the 12th Century it was marked “useless” but none-the-less kept. Despite its designated uselessness, the Fonthill Letter gives us a precious glimpse of everyday Anglo-Saxon red tape, as well as the high level of literacy in English which Alfred promoted.

The Ruthwell Cross is an 8th- or early 9th-Century sandstone monument around 16ft 4in (5m) tall which now stands inside the church at Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. It would once have been in the churchyard. (A replica of it appears in the exhibition.)

RCAHMS

RCAHMSFrom bottom to top, the front of the cross represents the Crucifixion; the Annunciation; Christ curing a blind man; Mary Magdalene drying Christ’s feet; and Mary and Martha. On the other side are depicted the Flight into Egypt; the hermits Paul and Antony; Christ recognised by beasts; and John the Baptist. The narrow sides have elegant vine-scroll ornamentation, around which is an unusual runic inscription of Old English verses that seem to echo and probably draw on the oral tradition of The Dream of the Rood (a ‘dream vision’ of the Cross), an Old English poetic masterpiece that survives in one place, as part of the Vercelli Book from the 10th Century.

Biblioteca Capitolare de Vercelli, Italy

Biblioteca Capitolare de Vercelli, ItalyThe first word, starting with the big ‘h’, is hwæt, or ‘Listen!’. (Runic ‘w’ looks like a ‘p’.) Since the English runes would have been unintelligible to the indigenous British population of the area, it has been speculated that the cross was a creation of an English monastic community.

The Anglo-Saxons seem remote – they are remote, for at their furthest they are over 1,500 years away from us – and we will probably never fathom many of the details of their lives, but there are also moments where they leap into focus and feel like they might be our grandparents, squabbling about this or that or telling stories in a letter. So much is both alien and familiar. It is fascinating to witness the evolution of the written language; and to imagine our descendants puzzling over our use of it in an exhibition 1,500 years from now.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.