Who decides what is cool?

The most powerful tastemakers are rebellious and idealistic. Cameron Laux on the arbiters who influence what we wear and how we live.

It was once largely the job of a handful of glossy print magazines to be the arbiters of taste in fashion. But now that the style commentators have dispersed into innumerable blogs, Instagram posts and other platforms – all of them grabbing the attention of people under 35, and sucking up advertising budgets as they go – the role of tastemaker is more complex.

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018There is the Business of Fashion, BoF, that started in 2007 as a simple one-man fashion blog but has grown to become a multifarious online fashion magazine and consultancy. A sniffle from BoF can cause fashion empires to catch a heavy cold. Then there is Highsnobiety, a streetwear website/multimedia brand/branding company (there are obvious synergies) that has achieved the holy grail in the post-‘legacy-media’ multiverse, and become a bastion of good taste.

More like this:

Highsnobiety’s daily bulletin email is mostly about limited-edition sneakers and clothes, though it can contain elements of broader cultural and creative analysis – music, film, fashion, some dalliance in the arts and design – that weave together to form a kind of lifestyle meta-commentary. 2018 was widely regarded as the year that streetwear came into its own. If you have any doubts about this, check eBay, where new pairs of rare trainers can change hands for giant sums: as I write, a pair of 1988 Nike Air Jordans are on sale for C$42,000 (£24,779) with 341 people ‘watching’.

The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018

The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018But the real story is the market in limited-edition trainers, T-shirts, tros, accessories, etc – whether new or on the proliferating resale platform – that many ordinary people are willing to shell out quite large sums of money for. In this context, the word ‘street’ refers to average people on the street, distinguished only by minute but obsessive refinements in taste that require them to master a large array of technicalities of pedigree and design, and then bond over them.

The current importance of streetwear largely explains the rise of designer Virgil Abloh. Abloh is about as ‘street’ as it’s possible to be. He rose to fame collaborating with rapper Kanye West on his Yeezy label, then went on to create his own Off-White label. Yeezy had a tendency to sell out immediately and then move onto resale platforms, and continues to do so, while Off-White gave underground fashionistas seizures as they threw their money at each limited ‘release’ of clothing. Abloh has broken the fashion internet more often and in more ways than anyone else over the past year.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNow Abloh has moved on to become creative director of luxury fashion house Louis Vuitton, which is no doubt hoping that Abloh will inject some of that consumer magic into its brand. The conjunction is logical: Abloh’s crude anti-aesthetic, which utilises adventurous materials with clashing colours, loud patterns, and even louder slogans, branding, and tags, should mesh well with the LV logo, which has become emblematic of wealth. Why not run with it? This uneasy stylistic line between elitism and accessibility is something that the arbiter of taste knows how to navigate.

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018In some respects, the concept of wealth itself has become tacky. And those who celebrate it have become the arbiters of taste – though not necessarily ‘good’ taste. An example might be the Goyard ‘Rich as Fuck’ suitcase that Kris Jenner’s family recently gave her for Christmas. This caused controversy. It is also possibly ironic, and fun to decode. On one level, by its absolute vulgarity, the slogan suggests that only fools care about degrees of wealth or style. And, in a sense, the whole Kardashian clan devote their lives to bringing an impeccable, and possibly democratic, lack of taste to their audience

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn another level – that of the suitcase’s approximate $15,000 (£11,765) price tag – they might also be saying that the only thing that matters is idiotic luxury, damn any social context, and with all the overtones of Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette’s ‘let them eat cake’ thereby implied. It’s also worth noting that Jenner’s family is itself a well-known 21st-Century brand. In the cacophony of the information age it is frequently necessary to incite controversy to sustain brand recognition – and to form high-profile brand ‘collaborations’. Kanye West is married to Kim Kardashian (total combined Twitter following: 88 million.)

Poster boys

This tightrope between elite vulgarity and accessibility, but not too much accessibility, is walked by Highsnobiety. To help us out in this minefield, it has recently published a bible of street fashion and culture that it calls The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide – because if it were ‘complete’ Highsnobiety would be the sort of snobbish authority it deplores, and its mission would be dead. The book defies expectations by being stimulating and something close to essential, if you happen to be a style geek or, its Japanese equivalent, an otaku. But even if you aren’t, it crackles with a fascinating countercultural confidence and imagination. It calls itself a ‘snapshot’ because the street-style scene changes rapidly, almost from week to week. You should probably be holding on to your Supreme hat as you read it.

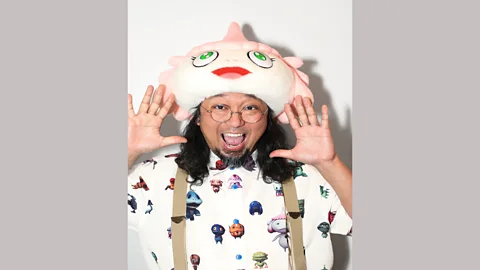

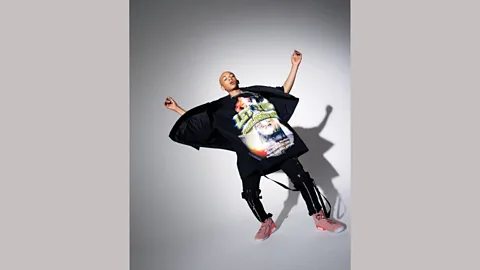

Streetwear in its current form is the offspring of 1970s and 1980s US hip-hop and punk, of skateboarding, surfing, street fashion, sportswear, and of casualwear movements that rose to prominence globally in the 1990s and thereafter. It venerates maverick individuality. Highsnobiety’s poster boys are an impressively eclectic group, including Jaden Smith, Jonah Hill, John Mayer, Skepta, Rick Owens, Pharrell Williams, Sean Wotherspoon, Hiroshi Fujiwara, A$AP Rocky, Takashi Murakami, and Tyler the Creator. (Highsnobiety is aimed at men.)

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018

Thomas Welch, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018All of them, as tastemakers, have immense credibility, in addition to wielding vast influence over an array of media platforms. They are all obsessive about maintaining artistic control over their image, and in talking about and debating their principles. The Incomplete Guide’s section on Pharrell Williams celebrates him as “One of hip-hop’s original originators, who made it totally acceptable to be totally weird”. Jaden Smith, whose identity is gender fluid, is called a “youth icon for every generation”. (He wears dresses when he feels like it. He has 11.1m followers on Instagram.) Tyler the Creator caused a hubbub by rapping about kissing boys, but he isn’t interested in being pinned down about it, or about anything else. It’s striking how open-minded these people seem, and how optimistic.

Kenneth Cappello, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018

Kenneth Cappello, The Incomplete Highsnobiety Guide, gestalten 2018The evolution of street style suggests that consumer culture is undergoing a metamorphosis and becoming involved in a youth-driven radical politics of identity. Mark Parker, the CEO of Nike, one of the big boys in the playground, contributes an interview to the opening pages of the Incomplete Guide. (It has a photo of him with his lips pressed into a grimace. Does the 63-year-old look uncomfortable?) He observes that “consumers also want to know what you stand for as a company,” and that it is important “to speak out against inequalities.” In 2018 a Nike advertising campaign conspicuously backed the American football player Colin Kaepernick, who caused controversy when he refused to stand during the US national anthem as a protest against racism. Kaepernick isn’t just a tastemaker, he has large political teeth.

It could be argued that streetwear companies and their associated influencers, large and small, are merely being cynical and playing to the narcissism of their millennial and post-millennial constituency. But even if that’s actually what they think they’re doing, they are still reflecting, and being shaped by, the values of their ‘target market’, a blend of street and digital cultures, or an emerging community. Doesn’t this suggest that all these people under 35 are more than just a market? Commercial entities like Nike have a tiger by the tail. Street style was political in its genesis – anarchic, creative, radically humane, fundamentally egalitarian – and it is likely to continue rubbing the mainstream up the wrong way. The culture and its opinion formers aren’t going to be tamed any time soon.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.