What connects Adam and Eve to Tinder?

Kunsthalle Bremen

Kunsthalle BremenA new exhibition looks at how love has been portrayed in art over centuries. Cath Pound explores depictions of carnal pleasure – and online dating.

Love is a subject that has inspired artists for centuries, if not millennia. And as more of us turn to dating apps to find love, the experience of online dating is something that contemporary artists have begun to explore. An intriguing new exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Bremen traces the various ways love and relationships have been portrayed in art across the ages, from classical ideals to the computer age. The five different sections – Proto-typical Couples, Real Couples, Self-Love, Beauty and the Erotic – reveal that although depictions and expectations of love may have changed, there are still some surprising parallels between ancient and modern experience.

More like this:

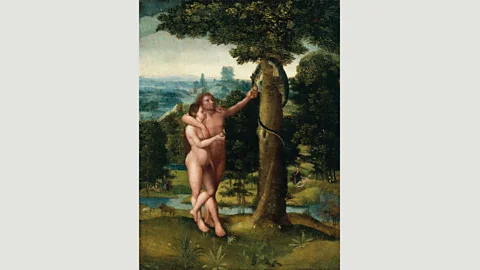

Adam and Eve were of course the original couple and have been portrayed by many of the greatest artists in history – generally used to illustrate the dangers of carnal pleasure and man’s sinful nature. Yet for curator Jasmin Mickein, when Eve is shown being tempted by the serpent (as in Adriaen Isenbrant’s portrayal of the couple from 1520), she also provided the template for all future relationships to follow – in quite a literal sense.

Kunsthalle Bremen

Kunsthalle Bremen“They both live in Paradise and are infatuated with each other and then there comes this moment when you realise the other one is not perfect and there is a crisis,” she says. Although fortunately it is doubtful if any contemporary issue could have quite as dramatic an outcome as plucking that apple.

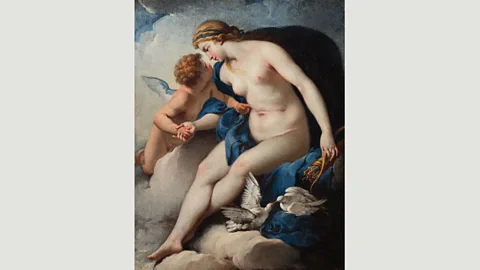

Mickein also sees parallels with online dating in the story of Cupid and Psyche, another couple who have inspired generations of artists. Psyche was spirited away by Cupid who would only come to her at night. “Eventually she finds out that ‘Oh my god, I’m sleeping with the god of love,’ and this is similar to this game of hiding and seeking in online dating where people are afraid to reveal their true selves,” says Mickein. The moment they finally do is “where the relationship starts”, she says.

Kunsthalle Bremen

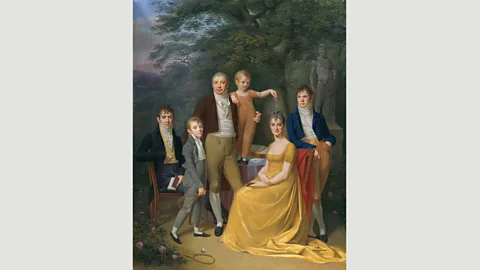

Kunsthalle BremenThe concept of real couples is closely linked to the idea of ‘romantic’ love which only really started to gain ground around 1800. Prior to that, kinship structure or economic and political necessity were often more import than love and if couples chose to be painted it was generally to signal a social or political union. A painting such as Carl Friedrich Demiani’s family portrait from 1806 is intriguing, as it appears to demonstrate the new freedom to marry for love.

First dates

Of course nowadays we are free to marry or date whoever we what. But this freedom can come with a downside as we embark on an endless stream of monotonous dates in a bid to find ‘the one’. The video artists Katharina Dacrés, Lena Heins and Jakob Weth mimic this tortuous process by filming couples sitting opposite each other while reciting the kind of bland dialogue which is depressingly familiar to anyone who has tried to make a connection via a dating app.

Dacrés, Heins and Weth

Dacrés, Heins and WethOnline dating is frequently criticised for its focus on looks but we are deluding ourselves if we think beauty hasn’t always been a major element of attraction, with every age having its own ideal aesthetic.

In the 19th Century, the Italian model Vittoria Caldoni was so adored by German artists living in Rome that “from this epoch all the faces look like her”, says Mickein. While the painter Anselm Feuerbach ired the classical good looks of the Italian model Anna Risi so much that he painted her at least 20 times. And it certainly wasn’t Sylvette David’s personality that attracted Picasso when he saw her in the garden next door and decided he wanted to paint her. Just as in the virtual world, “you simply find someone attractive and want to get to know them”, says Mickein.

Kunsthalle Bremen

Kunsthalle BremenBut of course beauty is a very subjective thing, a fact which was amply demonstrated by the Turkish photography artist Eylül Aslan when she decided to meet 25 men on Tinder and ask each of them what they found attractive about her and what they did not. Unsurprisingly each man gave a completely different answer. Aslan wittily collated them into a book mimicking Tinder’s swipe right for yes, left for no format with photographs of the ‘attractive’ parts of her body appearing on the right, the ‘unattractive’ on the left.

Eylül Aslan

Eylül AslanThe idea of ‘self love’ has generally had negative connotations in art history, with images of figures in front of mirrors being used to indicate narcissism. But for Mickein it is more about “reflecting on our relationships, how we treat each other and deal with our needs”.

It is something the Dutch artist Dries Verhoeven found himself contemplating after an extended period of using apps like Grindr. Verhoeven doesn’t believe “the online realm is less real then the offline one” – but he does think “they make us present different parts of who we are”. Online, Verhoeven found the focus tended to be on sex and casual hook-ups rather than intimacy, as “most gay dating apps don’t encourage you to be vulnerable and ambiguous,” he says.

Studio Dries Verhoeven, Photo: Willem Popelier

Studio Dries Verhoeven, Photo: Willem PopelierHe began wondering what would happen if he used “the sexually explicit domain, to also express other needs”. The result was Wanna Play? (Love in the time of Grindr), in which Verhoeven spent ten days living in a glass-fronted container while communicating with guys via a variety of apps – with whom he would then meet up to do non-sexual activities like cooking together or dancing. Verhoeven has since become “more critical of developments that make us objectify and compete with each other”, but its that although “on a Grindr diet, I still use it, when looking for sex”.

Flesh and blood

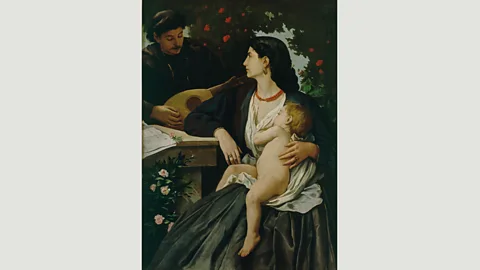

The erotic side of love has been a fertile source of inspiration throughout art history. Although artists couldn’t always be explicit, the woman with the magnificent cleavage in Christiaen van Couwenbergh’s 1632 painting Lovers leaves us with little doubt about her intentions towards the young man beside her as she gestures towards the bed.

Kunsthalle Bremen

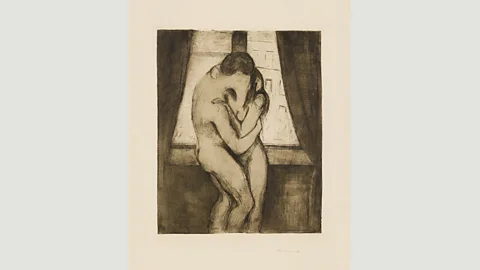

Kunsthalle BremenBy the late 19th Century, however, artists felt freer to challenge convention. In Munch’s 1895 print The Kiss, the lovers’ naked bodies seem to meld into each other in a never-ending embrace.

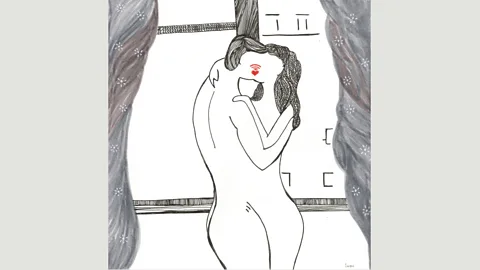

Kunsthalle Bremen

Kunsthalle BremenThis image would later inspire the Indian artist Indu Harikumar when she came to create the illustrations for her 100 Tinder Tales. Harikumar had asked people to send her their experiences of using the app, which she then published with an illustration inspired by their story. Instant Connection was the tale of a virtual relationship which ended up in the bedroom five minutes after the couple met for the first time in real life and then blossomed into enduring love.

Indu Harikumar

Indu HarikumarBut it is of course Venus herself, the goddess of love and mother of Cupid, who has proved to be the ultimate artist’s muse when it comes to the depiction of love and desire, even though her own love life was far from a perfect idyll.

Kunsthalle Bremen

Kunsthalle Bremen“Venus was married to Vulcan but Cupid is not their child, he is the result of an affair with Mars,” explains Mickein. “Love is not simple or clear. Love is complex,” she says. With or without the help of the internet, nothing is ever going to change that. Which is perhaps why no more perfect embodiment of love could ever be found.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.