Why tyrants love to write poetry

Alamy

AlamyNero, Stalin and Bin Laden were all fans, but what makes verse so appealing to these leaders? Benjamin Ramm explores the connection between ruthlessness and sentimentality.

Poetry is an art of refinement, synonymous with delicacy and sensitivity. It seems counterintuitive that it might also be a celebration of brutality, and the art form beloved of tyrants. But from classical antiquity to modernity, dictators have been inspired to write verse – seeking solace, intimacy, or glory. Their work informs us about the nature of power, the abiding appeal of poetry, and the perils of artistic interpretation.

The archetype of the poet-tyrant is Roman emperor Nero (37-68 CE), the vain, self-pitying exhibitionist whose debased rule mirrored his deficient art. Nero’s historiographers, Tacitus and Suetonius, suggest that Rome was as tormented by his poetry as by his policies. Derision is a satisfying form of critical revenge, but these s raise a troubling question: would the tyrant’s crimes be mitigated were his art deemed to have merit; and conversely, can we judge fairly the quality of a tyrant’s poetry?

As the scholar Ulrich Gotter points out in the recently published volume Tyrants Writing Poetry, in comparison to poet-emperors Caesar and Augustus, Nero’s reign was "remarkably bloodless". Yet despite his lack of military ambition, Nero’s vengeful deeds were high-profile, and our image of him is of a pathetic despot, wearing a tragic stage costume, singing of the capture of Troy while his imperial city burned to the ground; Suetonius quotes Nero as “being greatly delighted with the beauty of the flames”.

Nero revelled in performance: in Rome he inaugurated an elaborate Hellenic-inspired festival, the Neronia, and during a tour of Greece he participated in competitions of poetry, song and lyre-playing, as well as charioteering. (At Olympia, he was thrown from his 10-horse chariot but was still crowned the winner by fawning, fearful judges). Nero insisted that the statues of previous winners be ripped off their pedestals, and he returned to Rome with 1,808 prizes.

Alamy

AlamyThis portrait of the poet as megalomaniac, forging the world from his delusional imagination, provided inspiration for artists such as the Marquis de Sade and the Nobel prize-winning author Henryk Sienkiewicz, whose 1896 novel Quo Vadis became an iconic Technicolor film starring Peter Ustinov. Nero even sought to choreograph his final performance – his own botched suicide. He rehearsed and performed his farewell phrase: qualis artifex pereo (“what an artist dies with me”).

‘The magic power of the spoken word’

Almost two thousand years later, a group of Italian poets prefigured fascism with a Neronian celebration of the spectacle of destruction. ‘Let art flourish, though the world perish’ was one of the slogans of the Italian Futurists, founded by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who fetishised war as ‘the only cure for the world’. Marinetti sought to industrialise and militarise language with ‘concrete poetry’, written by a creator-aggressor who would ‘begin by brutally destroying syntax’. The Futurists had been influenced by poet-warrior Gabriele D’Annunzio, a revered figure who set up a short-lived ‘lyrical dictatorship’ in 1919, which inspired Mussolini’s seizure of power three years later.

Despite professing enthusiasm for D’Annunzio’s ‘mystical union’ of poet and people, Mussolini’s own verse was prone to mawkish resignation. There was a degree of pretence in his literary ambition: his biographer Richard Bosworth notes that Mussolini left the works of eminent poets “ostentatiously open on his desk when being visited by foreign dignitaries”. His later poetry reflected his isolation, far from the idealism of his socialist youth, which produced verses that lamented the fall of Jacobinism (“the axe bloodied in plebeian veins”) and yearned for revolutionary prophecy (“In his dying eyes flashed the Idea, / The vision of centuries to come”).

Inevitably, dictators channel their artistic disappointments into politics. Hitler, despite proclaiming a preference for ‘the magic power of the spoken word’ against ‘the syrupy effusions of aesthetic litterateurs’, once imagined himself a Viennese bohemian. Goebbels, who perfected the art form of propaganda, wrote a novel with expressionistic traits, while Pol Pot, educated in Paris, was an irer of Verlaine’s Symbolist poetry.

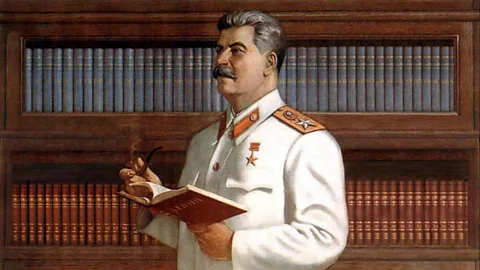

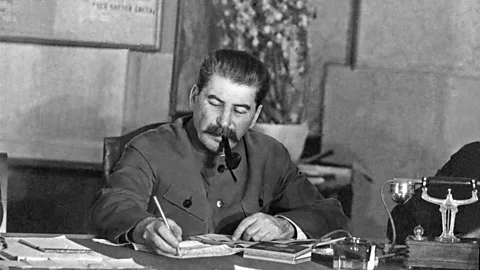

Alamy

AlamyRussian Marxism initiated a wave of radical aesthetic movements, but the poet-tyrant of the Soviet Union wrote in a strikingly conservative style. The young Stalin composed poetry in Georgian – a language banned at the Orthodox seminary where he trained – and his work reproduces romantic motifs, of the rebellious poet and the lost Golden Age. Stalin’s verses are characterised by artful imitation, a lack of self-irony, and “exaggerated ardour”, according to critic Evgeny Dobrenko.

With an ornamental elegance bordering on kitsch, Stalin’s poetry brims with naturalistic clichés: “under a grove in the azure rings the warble of a nightingale”, as the soul is tormented by “the dark forest of the night”. It is earnest, if politically crude:

Know for certain that once

Struck down to the ground, an oppressed man

Strives again to reach the pure mountain,

When exalted by hope.

In Over This Land (1895), an artist bestows revelatory music to the masses:

The voice made many a man’s heart

Beat, that had been turned to stone;

It enlightened many a man’s mind

Which had been cast into uttermost darkness.

But the prophet is unrecognised by those he seeks to liberate: “The mob set before the outcast / A vessel filled with poison”. Stalin reappears as a singer in a later poem, “moved to tears by the bitter lot of the peasant”, as he – with foresight – “erected a monument to himself… in the heart of every Georgian”. Published anonymously, Stalin’s poetry featured in prestigious literary journals and was anthologised as an exemplar of Georgian classical literature.

Alamy

AlamyIndeed, even Stalin’s most critical biographers have praise for his verses: Simon Sebag-Montefiore wrote that “their beauty lies in the rhythm and language” (difficult to convey in translation), while Robert Service claims that the work possesses “a linguistic purity recognised by all”. Its decorative prettiness and heroic posturing would reappear in Stalin’s championing of socialist realism, against an experimental modernist avant-garde.

Pen and sword

Stalin’s spiritual heir, Yuri Andropov, combined the bureaucratic with the romantic. As head of the KGB, he persecuted dissidents and crushed the Hungarian uprising, while writing love poems to his wife. (The ability to compartmentalise is an essential trait of the creator-dictator). The Uzbek poet Hamid Ismailov tells a revealing anecdote of Andropov: one of his speechwriters sent him a birthday card, in which he joked that power corrupts people, to which Andropov replied with a chilling verse:

Once a villain blurted out

that power corrupts people.

Now all pundits repeat it

For so many years

Without noticing (alas!)

That more often people corrupt the power.

Another avowed Stalinist, the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, was attributed the authorship of revolutionary plays and theoretical work, most notably ‘seed theory’, which presents Kim as the sire of artistic invention. In 1992, Kim Sr wrote a public poem to his son, Jong-il:

Can it be the Shining Star’s fiftieth birthday already?

ired by all for his power of pen and sword

Combined with his loyal and filial mind,

And unanimous praise and cheers shake heaven and earth.

Alamy

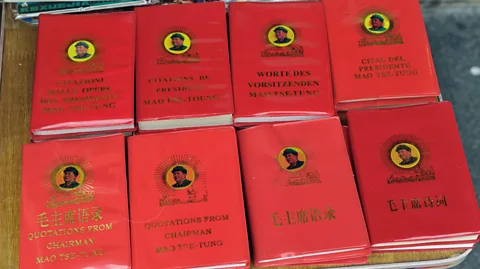

AlamyKim, father of the nation, was heralded as the ‘Sun of the Nation’, in the manner of Mao Zedong (‘the Red Sun in our Hearts’). It is Mao who embodied the pen-and-sword ideal of a ruler, based on a unity of cultural ability (wen) with martial prowess (wu). Mao sought to appropriate the imperial tradition while transcending it, noting in a 1936 poem that few emperors had left a literary legacy: now “truly great men / Look to this age alone”.

Mao’s poetry is orthodox in form and classical in theme, a performance of the tradition he purported to despise. Despite his own injunction to destroy the Four Olds (culture, customs, habits, ideas), Mao wrote in the old style, even when it had been denounced as elitist and outdated. “I feared the spread of such errors could lead the youth astray”, confided Mao to a magazine editor, but he indulged his own tastes nonetheless, even as he forbade others.

Alamy

AlamyMao luxuriated in language, proving adept with imagery (“The rolling hills sea-blue, / The dying sun blood-red”) and classical themes (“Man’s world is mutable, seas become mulberry fields”), in turns epigrammatic (“Bitter sacrifice strengthens bold resolve”) and propagandistic (“China’s daughters have high-aspiring minds, / They love their battle-array, not silks and satins”).

Alamy

AlamyMao’s work is proof that artistic refinement is no guarantee of a gentler politics. In 1966, Red Guards supplemented their Little Red Book with a collection of 25 poems attributed to Mao, which led to an enthusiasm for old style verses among those dedicated to destroying “feudal relics”. The last line that Mao ever wrote, a year before launching the Cultural Revolution, was a premonition of the coming tumult: “Look, the world is being turned upside down”.

‘Censor and creator’

Poetry has been entered as incriminating evidence at the International Criminal Court, where Radovan Karadžić, the ‘Butcher of Bosnia’, was found guilty of genocide. A 1992 BBC documentary captured a meeting between Karadžić and the nationalist Russian poet Eduard Limonov, in which Karadžić recites a poem that prophesies violence and Limonov fires a volley of bullets into the valley below. Karadžić claims to have anticipated the battle years beforehand, and his 1971 poem Sarajevo contains the lines:

The town burns like a piece of incense

In the smoke rumbles our consciousness…

I know that all of these are the preparations of the scream:

What does the black metal in the garage have for us?

Establishing intention on the part of a perpetrator is a requirement under international law. Karadžić was a key figure in what Slavoj Žižek the ‘poetic-military complex’, which venerated the literary canon of nationalism, particularly Petar Petrović-Njegoš’ epic poem The Mountain Wreath (1847), in which the shedding of Muslim blood is presented as an act of baptism for the Serb nation.

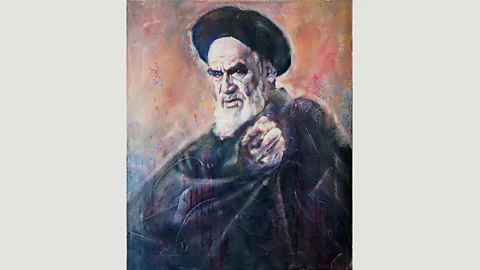

The rhetoric of genocide is cloaked in anodyne metaphor: a nation ‘purified’ through ‘ethnic cleansing’. Yet readers must also be aware of the perils of treating an artistic persona as the author’s own. Consider the work of Ayatollah Khomeini, whose Persian poetry channels the spirit of Sufi seers Rumi and Hafez:

I am a supplicant for a goblet of wine

from the hand of a sweetheart.

In whom can I confide this secret of mine?

Where can I take this sorrow?

These lyrics are difficult to reconcile with Khomeini’s public persona:

I have become imprisoned, O beloved, by the mole on your lip!

I saw your ailing eyes and became ill through love…

Open the door of the tavern and let us go there day and night,

For I am sick and tired of the mosque and seminary.

The ayatollah’s devotees are keen to read these verses strictly allegorically (‘The mosque and the preacher are the empty display of outward religiosity’) – although some lines are difficult to neuter: “I have torn off the garb of asceticism and hypocrisy”. The poems reveal the ayatollah as a mystic, albeit one who can issue a fatwa, making him both censor and creator.

Alamy

AlamyThe raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in 2011 prompted media commentary about his bookshelf, focusing on the absence of fiction and neglecting to mention his fondness for poetry. In 2010, bin Laden wrote to a lieutenant with details of an ambitious plot, before adding a request: “if there are any brothers with you who know about poetic metres, please inform me, and if you have any books on the science of classical prosody, please send them to me”.

Bin Laden was among the most celebrated jihadi poets, and his status derived in part from his mastery of classical eloquence. Bin Laden’s emir in Iraq, Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, was known simultaneously as ‘the butcher’ and ‘he who weeps a lot’ – illuminating the link between ruthlessness and sentimentality, the twin desire for power and pity. Al-Qaeda’s current leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, also writes poetry, and the self-proclaimed caliph of so-called Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, wrote his PhD thesis on a religious poem.

Alamy

AlamyOne tyrant who wrote poetry to the bitter end was Saddam Hussein. His 2013 prison poem is composed in a clumsy vernacular: “You are the soothing breeze / My soul is made fresh by you / And our Baath Party blossoms like a branch turns green”. Saddam, who liked to pose with a Kalashnikov, exhibits his trademark defiance: “Here we unveil our chests to the wolves”. Intriguingly, the man who invented the rifle, Mikhail Kalashnikov, himself wanted to be a poet. As WH Auden wrote in an epitaph of Hitler, “the poetry he invented was easy to understand”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.