The 25 greatest foreign-language films

Alamy

AlamyInternational critics reveal why these non-English language films are classics of world cinema.

Alchetron

AlchetronIn his tragically short career, the Taiwanese director Edward Yang was a master of transmuting grand socio-political narratives into something deeply intimate: the story of a young couple or a family could be the story of a city, a country, an entire era. Yi Yi, his final film, was his supreme masterpiece, a near-three-hour portrait of the middle-class Jian family in Taipei that encomes weddings, love triangles, and funerals, as well as the more mundane traumas and delights of ordinary life. It is a film that plunges you into lives that feel fully lived with the confidence of a great novel; it thrives on details while being undeniably sweeping. It’s hard to imagine any director eclipsing such a film, and yet it’s equally painful to consider that Yang never had the chance to try. – David Sims, The Atlantic, US

Alamy

AlamySergei Eisenstein’s dramatisation of the mutiny which took place on the Russian battleship Potemkin in 1905 remains a technical masterpiece, despite being made over 90 years ago. Throughout the film, Eisenstein tested his theories of montage to induce the maximum emotional response from audiences, and his experiment resulted in a number of unforgettable moments; the Odessa Steps sequence has received homages from numerous films including, yes, The Untouchables. Its cinematic power makes it one of the most influential works in movie history. – Seongyong Cho, freelance, South Korea

Alamy

AlamyCarl Theodor Dreyer’s groundbreaking The ion of Joan of Arc demonstrates the power of cinematographic language at its best. A black-and-white silent film, it manages to tell the story of a trial using lighting and contrasts, and framing filled with dramatic symbolism and great beauty. The intense close-ups of Maria Falconetti’s tortured face, the high-angle shots of her, the low-angle shots of her frowning inquisitors… together these create some of the most heart-rending scenes in film history, and one of the most tragic, humiliated, and graceful of cinema’s heroines. – Ana Josefa Silva, Bio Bio Radio, Chile

Alamy

AlamyWith Pan’s Labyrinth, Guillermo del Toro became the superb film-maker the world celebrates today (his latest film, The Shape of Water, won four Academy Awards). He had already shown his great talent as a creator of fantasy, but he had yet to deal with a big topic based in reality. And what a topic Pan’s Labyrinth addresses: the horror of the Spanish Civil War, as seen through the eyes and the imagination of a young girl. Or, for that matter, as seen through del Toro’s eyes and imagination, which are as fantastic as the magic of cinema can be. – Mauricio Reina, El Tiempo, Colombia

Alamy

AlamyEveryone is fighting a battle in A Separation. Simin battles with her husband Nader, Nader with Simin, their servant Razieh battles with herself, and Razieh’s husband battles with everyone and everything. But Asghar Farhadi depicts the domestic combat with the utmost calm, placing a multi-faceted portrait of Iran in the background. Like Simin and Nader’s little daughter Temeh, we watch the goings-on with anxiety. Each and every battle is familiar and human. Whose side are we on? Who are we to believe? In the final scene, Nader and Simin sit on either side of a glass partition without looking at each other. When the end credits roll through the little corridor that separates them, we are still questioning them, and ourselves. – Elcin Yahsi, Ekranella, Turkey

IMDB

IMDBThe Mirror is one of the most subjective and personal films not only in Andrei Tarkovsky's canon but in world cinema. The main character, a dying poet recalling his life, is the director’s alter ego. The director’s father, the great poet Arseny Tarkovsky, reads his own poems. The narrator comments on fragments of the director’s childhood over images of his mother (played by the magnificent Margarita Terekhova). And Andrei himself appears on the screen in a small episode. But the music by Edouard Artemiev and the photography by Georgy Rerberg contribute greatly to this masterpiece’s dreamlike beauty. – Kirill Razlogov, Russian Guild of Film Critics, Russia

Alamy

AlamyI first saw The Battle of Algiers at one in the morning on television. I couldn’t sleep for hours afterwards, such was the film’s incendiary action and its withering representation of the violence of colonial occupation and anti-colonial insurrection. The film was revered, but copies were difficult to come by – mostly ropey VHS tapes with poor sub-titles. The DVD re-release by Criterion restored not only the film’s full length, but also – from first frame to last – the alchemy of beauty, terror, anger, and anguish that is hard to find in any film in any language. More importantly, The Battle of Algiers is as relevant today as it was in 1966. A revolutionary film, and the one of the greatest films about revolution. – Ian-Malcolm Rijsdijk, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Asiatheque

AsiathequeSet in mid-1940s Taiwan, when the Kuomintang government took control of the island from Japan’s colonial rule, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s historical drama appears to be a chronicle of the misfortunes of the Lin family. But Hou used the Lins to put the dark history of Taiwan in the spotlight. What seem to be mundane events experienced by the four Lin brothers illustrate the pain and struggles of the Taiwanese during the times of February 28 Incident, when the government’s bloody suppression of the widespread uprisings in 1947 killed thousands of people. Hou’s film was released just two years after 38 years of martial law had ended, and it forced people to re-examine this period. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the first Taiwanese film to be awarded the honour. – Vivienne Chow, freelance, Hong Kong

Alamy

AlamyAs the characters of Aguirre, the Wrath of God descend into madness in their doomed rainforest search for the fabled city of El Dorado, so too, perhaps, did film-maker Werner Herzog and his star/muse/monster Klaus Kinski while making the film. Even the viewer gives in to something approaching a perceptual shift from the very start, as we follow the group of conquistadores down a narrow, mist-covered mountain path while Herzog’s quasi-documentary approach and Kinski’s terrifying performance mesh with the ethereal soundscape to transport us elsewhere. By the time Aguirre is last man standing (amid scores of monkeys, of course), still pledging to endure as the “Wrath of God”, his world is spinning, and so is Herzog’s camera. And so are we. But as Aguirre asks everyone, yet no one, “Who else is with me?”, you’d be excused for raising your hand. – Scott Collura, IGN, US

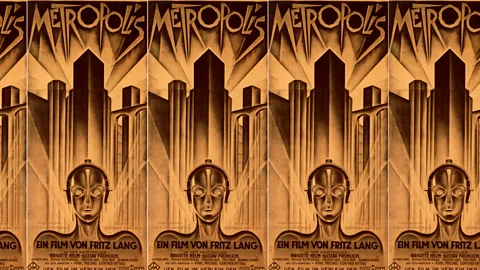

Alamy

AlamyGreat science fiction always depicts contemporary reality, rather than the future. Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou, his wife and co-writer, made Metropolis as a picture of the gorgeous chaos of the Weimar Republic. It was not a prediction of things to come but a reflection of the times. But Lang 's cool direction and grand vision created a world which nobody had ever seen. We are still caught up in that world. Almost every subsequent science-fiction movie is influenced by Metropolis. But nobody has ever made a robot as sexy and alive as Maria. – Kiichiro Yanashita, freelance, Japan

Alamy

AlamySatyajit Ray's Pather Panchali was criticised by some people in India for selling what in today’s is called ‘poverty porn’. But poverty was only a backdrop on which Ray projected the daily joys and sorrows of the people of rural India – to be specific, of Bengal – in their purest form. He captured the lives of the characters in the most realistic style without any melodramatic flourish. Who can forget the heart-wrenching moment when Harihar returns home after a long absence to find that Durga has died, or the great joy of Apu and Durga when they run amidst the “Kaash” flower fields to catch a glimpse of the train? Inspired by Italian Neorealistim, Ray gave the world an all-time classic and changed the face of Indian cinema forever. – Utpal Borpujari, freelance, India

Alamy

Alamy“I had not any other intentions but to tell the story of what happened to Jeanne Dielman between Tuesday 5pm and Thursday 6pm in the same week.” A tribute to Chantal Akerman’s mother, a powerful presence looming over many of her films, Jeanne Dielman is as deceptively straightforward as that synopsis provided by its writer-director before its world premiere. Played by Delphine Seyrig, Jeanne could be any anonymous single mother, buying the groceries and preparing the meals, far from where movie cameras usually fix their attention. But it’s not just Jeanne’s secret prostitution that establishes her as a more complicated figure – it’s through Akerman’s sympathetic, real-time portraiture that we begin to appreciate the everyday lives of women who have been marginalised by society and cinema. Jeanne Dielman’s formal rigour and held tension lead to one of film’s most shocking acts of violence. Its catharsis still resonates decades later. – Tim Grierson, Screen International, US

Alamy

AlamyBefore our cinematic serial killers became memes – slick things with a penchant for Phil Collins albums – it was radical to put them at the centre of a thriller. Fritz Lang’s 1931 game-changer, the first major film to do so, invented the grammar of criminal obsession: the thumbing through of documents, the tightening of manhunts, the depiction of unhealthy appetites. And still, decades later, M has two traits that few directors have followed up on. It makes Hans Beckert (an inspired Peter Lorre, forever defined by this role) a weak and broken man, far from superhuman. And it turns his sickness into a symptom of a flawed society, one that’s grubby, ugly and, in Lang’s critique, trending toward evil. We need to understand this film. – Joshua Rothkopf, Time Out New York, US

Alamy

AlamyChen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine tells the story of two Peking Opera actors' fluctuating fortunes, from childhood onwards, but it is actually about the age of time, about glory and decay, about persevering love and hatred. A sumptuous, ambitious, unpredictable epic, it sweeps the viewer through 52 tumultuous years of Chinese history, from 1925 to 1977, as the characters are kicked back and forth by warlords, Japanese invaders, communists and the Cultural Revolution. The actors contribute the best performances ever in a Chinese film, and Farewell My Concubine was the t winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1993. – Huang Haikun, Movie View, China

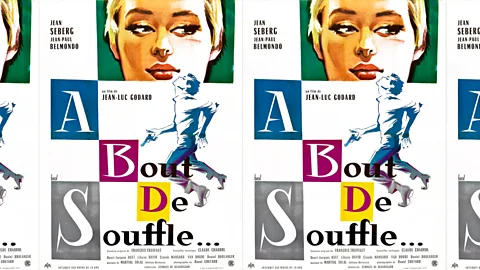

Alamy

AlamyThe innovations introduced by Godard in his debut feature have been extensively documented: the jump cuts; the improvised script; the circular dialogue; Martial Solal’s temperamental score; Raoul Coutard’s gorgeously naturalistic cinematography; Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg’s iconic freewheeling performances. Godard did not deliberately destroy cinema, as Susan Sontag put it in 1968, but he certainly reinvented it. With Breathless, he demonstrated the limitless possibilities of what cinema can do and be – and for the next 58 years, he would continue to do so. At once dreamy yet cynical, ingenuous and violent, clear-eyed and mysterious, mischievous and ultimately melancholic, this is where modern film was founded. Godard wanted to be Howard Hawks; instead, he became cinema’s James Joyce. – Joseph Fahim, freelance, Egypt

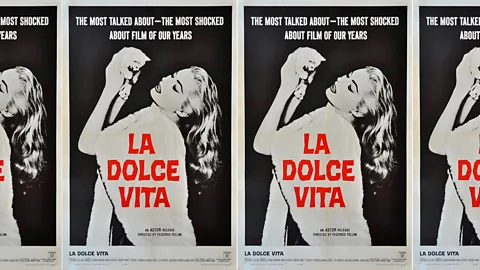

Alamy

AlamyLa Dolce Vita is the masterpiece of the Italian auteur par excellence, Federico Fellini. It encapsulates a historical era (the Italian economic ‘miracle’), it is provocative in of gender and sexuality, and it focuses on Italian identity and the myth of Rome in Anglo-American culture (the famous scene with Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain). It is the story of a journalist, Marcello, who wanders around the legendary Via Veneto, bumping into directors, photographers, models and artists. He runs from one woman to another and from one adventure to another, to discover, at the end, that “the sweet life” is not so sweet. – Vito Zagarrio, University of Rome, Italy

Alamy

AlamyLoneliness and longing permeate the smoky, colourful atmosphere of Wong Kar-wai’s dreamy In the Mood for Love. After two neighbours find out that their husband and wife had an affair with each other, they strike up an unusual relationship. Breaking down all the conventions of cinematic love stories, the characters barely touch and only allow slivers of their inner lives to peek through. In the Mood for Love is a film that ripples with textures and sensual energy as the camera becomes preoccupied with small gestures: the rattling of mahjong tiles, the way fabric bends, hands leaning on a tabletop. It is a film where absence is infused with beauty, poetry and romance. – Justine Smith, freelance, Canada

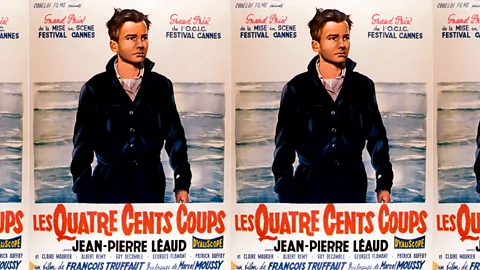

Alamy

AlamyThe film that launched the French New Wave in 1959 looks at the world with anguish and wonder through the eyes of a neglected boy, Antoine Doinel. Loose camera movements open up the claustrophobic spaces that cage him, and when he breaks out, The 400 Blows becomes an ode to Paris – not the city of lights but a lived-in metropolis where kids run in streets adorned with muddy fountains. Deceptively simple yet insightful and emotionally deep, François Truffaut's semi-autobiographic film is the most lively, fresh and authentic depiction of the spirit of youth, right up to the final melancholic note. Antoine is strikingly embodied by the 14-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud, who would grow up to be the face of the New Wave – yet his first film is still the best. -– Yael Shuv, Time Out, Israel

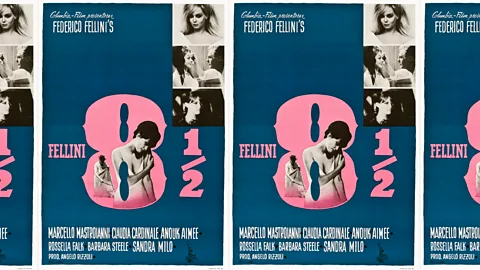

Alamy

AlamyDreamy, extravagant and impossibly stylish, Fellini’s 8 1/2 stars Marcello Mastroianni – rocking a black suit as only he could – as Guido Anselmi, a burnt-out film director who checks himself into a spa. Harassed by his nagging producer, pushy journalists and the women in his life, Guido flees reality and daydreams about his past. The resulting ‘confusion’ proves to be a blessing – by letting his imagination wonder, he finds his way back to art. The endearing Guido was Fellini in disguise. The director had decided to bow out of the project, claiming he had “lost his film”. He was about to tell his producer about this decision when he realised that he had a story to tell, after all: the journey of a film-maker who loses – and then finds – the plotline of his film. – Fernanda Solorzano, Letras Libras, Mexico

Alamy

AlamyTwo identities – a nurse (Bibi Andersson) and an actress (Liv Ullmann) who's been struck mute – fracture and merge in Ingmar Bergman's most radical and stunning achievement, a work of fierce modernist provocation and unsettling formal brilliance. Other Bergman films explore the human comedy or the stark agonies of the world in sorrowful , but this feels near-forensic: a slicing inquisition into female consciousness which plays out like a troubling therapy session. As these two women spar and test each other at a beach house, Bergman makes the air between them crackle with static charge at every secret or disclosure. – Tim Robey, Daily Telegraph, UK

Alamy

AlamyJean Renoir ’s magnum opus, about a hunting party at a French chateau, was filmed on the eve of World War Two and reviled upon its release. But Robert Altman later said, “I learned the rules of the game from The Rules of the Game.” Renoir let his cast improvise during the shoot, and the dichotomy between the chaotic narrative and meticulously-planned long takes gives the picture the documentary feel that Altman film would emulate. As farce leads inexorably to tragedy, two celebrated set-pieces – the grand hunt and a Danse Macabre, set to Saint-Saëns’ tone poem – foreshadow the “unfortunate accident” at the end of the film. They also sound the death knell for an epoch that was about to be annihilated. – Ali Arikan, Dipnot TV, Turkey

Alamy

AlamyRashomon is a very special whodunnit. Three men seek refuge from the rain in the ruins of an old gate. One of them narrates a sombre story – a samurai has been murdered – but there are four different s of the deed, all contradictory. Kurosawa superbly exposes the complexity of human nature via the crazy impulsiveness of the thief, Tajômaru, the cold cruelty of the samurai, the survival skills of the wife. They all have been thrown into an impossible situation. What makes this film a masterpiece for the ages is that you can relate to the characters’ volatile emotions. When confronted by ugliness, you are not sure of how you will react. Until you do. – Adriana Fernández, Reforma, Mexico

Alamy

AlamyYasujirō Ozu’s 1953 film, about an elderly couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their dismissive adult children, was initially considered too Japanese for audiences outside the country — despite being loosely based on an American film. By the 1970s, though, critics around the world had started to see it, and it was recognised as the masterpiece that it is: a poignant drama that accrues emotion so slowly that it sneaks up on you. Ozu’s distinctive low-angle and static shots have been a touchpoint for directors ever since, both in Japan and abroad. And the film has not lost one ounce of its power. – Alissa Wilkinson, Vox film critic, US

Alamy

AlamyNo matter who you are, where you are from, or which language you speak, the last minutes of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves will break your heart. The film revolves around a father and son in post-World War Two Italy, searching for a stolen bicycle. What it showed us, in 1948, was Italian Neorealism’s new and exciting way of making movies. Since then, it has shown us that tenderness and sincerity overcome every language and geographical barrier. That’s one reason why it has influenced almost every great film-maker since. Even at the age of 70, De Sica’s masterpiece is still relevant to every country, to every parent, to every human being – Orr Sigoli, freelance, Israel

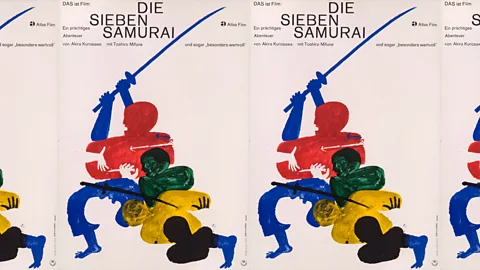

Getty

GettyThe glorious black and white. The wandering eyes of multiple cameras. The inspired use of the latest technology, the telephoto lens, that takes us into the very heart of the fray. The use of action as character exploration: how they fight, how they deal with weapons, what they have lost, what they lust after, where they stand. The ellipses: a man enters a shack, another man leaves, stumbles, balances for a second, falls down and dies. And then Kurosawa unleashes the storm, and an epic confrontation plays out like a symphony. Seven Samurai created not only a whole new approach to action cinema but a whole sub-genre: films about a team of unlikely heroes on an impossible mission, fighting for their own souls. – Ana Maria Bahiana, UOL, Brazil