Operation Mincemeat: The incredible plot that tricked Hitler

Alamy

AlamyIn 1943, British agents hatched an elaborate plan to mislead about UK invasion plans – and it's now inspired both a Colin Firth film and a stage musical, writes Natasha Tripney.

It's a story so fantastic and macabre that it feels like the product of a writer's imagination. In 1943, at the height of World War Two, British Intelligence agents hatched an elaborate scheme to convince the Germans that the Allied forces were planning to invade Greece rather than Sicily. The plan, code-named Operation Mincemeat, involved planting forged documents upon a dead body before setting him adrift in neutral Spanish waters, with the aim of the papers ending up in German hands.

The false intelligence found its way onto Hitler's desk and was evidently believed as ordered tanks divisions, artillery and boats to defend Greece, Sardinia and the Balkans. When Allied troops invaded Sicily on 10 July 1943, the Nazis were caught unawares.

More like this:

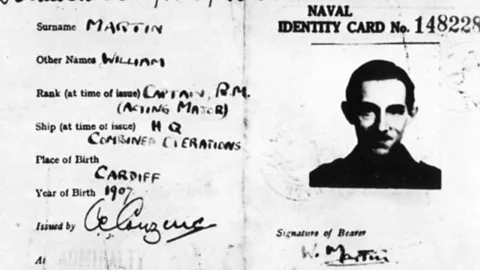

The deception succeeded, in part, because the naval intelligence officers behind it, Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley, were so invested in the fiction. They created a convincing backstory for the corpse, a whole new identity: a homeless person named Glyndwr Michael, who had died after ingesting rat poison, was transformed into William Martin, an officer of the Royal Marines. They gave him not just a name and rank, but an entire life including a fiancée waiting for him at

home.

Alamy

AlamyAuthor and historian Ben Macintyre's gripping 2010 of the story is now the basis of a film, also called Operation Mincemeat, directed by John Madden, of Shakespeare in Love and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel fame. It stars Matthew Macfadyen as Cholmondeley, the ungainly aspiring airman who was stymied both by his height and his poor eyesight and seconded to the British security service, MI5, who first suggested the plan, and Colin Firth as Montagu, the shrewd peacetime lawyer who helped develop it.

"They worked together to build this completely imaginary world," explains Macintyre. Working alongside formidable Hester Leggett and the ambitious young secretary Jean Leslie (played by Penelope Wilton and Kelly Macdonald), they sourced an ID card, a uniform, the underwear befitting an officer, and furnished Major Martin with all manner of "wallet litter". This included a note from his bank manager, saying he was overdrawn; receipts and ticket stubs from various theatres and clubs, to demonstrate his appetite for nightlife; and, most poignantly, love letters from his beloved "Pam", with whom he'd had a whirlwind wartime romance. They even gave him an engagement ring.

The creation of the ultimate war story

There's a real sense that these people lived vicariously through their creation. "These were people who were unable to take part in the actual war on the battlefield, either because they were too tall, like Cholmondeley, or too old, like Montagu, or they were women like Jean and they imagined themselves into a kind of parallel underground war," says Macintyre. "There's something touching and remarkable about the idea of a hidden hero."

In building a life for Martin, the Operation's team were forced to draw on their creative resources, and needed to think like writers. And writers abound in the Mincemeat story, something the film plays up. The so-called "trout memo" – a list of potential ways to deceive the enemy which inspired Cholmondeley and Montagu – was likely written by James Bond author Ian Fleming, then assistant to iral James Godfrey, who in turn got the idea from a novel written by another espionage man-turned-fiction writer Basil Thompson. In the film you can see Jonny Flynn's Fleming absorbing every outlandish detail for future use.

"I think it's no accident, in a way that some of the greatest novelists of the 20th Century were also spies: Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, John Buchan, John Le Carré," says Macintyre. "So much of what spies do is to create a false world and convince someone else that is true."

This was part of the appeal for writer Michelle Ashford, who adapted Macintyre's book for the screen, having read and loved it when it was first published. "It's almost like a Valentine to spy stories," she says. "And how ironic that the creator of James Bond was actually one of the architects of the story."

"I love the notion that the whole course of the war was changed by this small group, hunkered down in a smoky, depressing, windowless basement room," says Ashford. "That they were the ones that made the difference."

Alamy

AlamyFittingly, this true story in which fiction plays a part has frequently been fictionalised. In 1950, Duff Cooper, a former cabinet minister, published the novel Operation Heartbreak, a thinly veiled version of events. When challenged that in doing so he was divulging official secrets, Macintyre explains, Duff reasoned that "Winston Churchill was telling the story after dinner every night, so why shouldn't he tell it">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });