The sci-fi genre offering radical hope for living better

María Medem

María MedemIn these times of cynicism and despair, is 'hopepunk' the perfect antidote? David Robson explores radical optimism, and why it matters.

Alexandra Rowland didn't mean to spark a new artistic genre. In 2017, however, the fantasy author had a moment of inspiration. Rowland had been contemplating the rise of grimdark – the subgenre of fantasy fiction typified by George RR Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire (the inspiration for the TV series Game of Thrones) – which emphasises the flaws in human nature, and focuses on our capacity for cruelty.

But what could describe literature that instead focuses on our capacity for good? "The opposite of grimdark is hopepunk. it on," wrote the author in a short post on Tumblr. The post soon went viral – and by 2019 the term had entered the Collins English Dictionary, defined as "a literary and artistic movement that celebrates the pursuit of positive aims in the face of adversity".

More like this:

Various works of fiction – including the Lord of the Rings and Terry Pratchett's Discworld series – have now been labelled as examples of hopepunk, along with a slew of contemporary writers.

"Cautionary tales are very important," says Becky Chambers, one of the leading authors associated with the hopepunk movement, who has won a much-coveted Hugo Award for her sci-fi Wayfarer series. "But if that is all that you have, you risk nihilism."

In the midst of current political, economic and environment uncertainty, many of us may have noticed a tendency to fall into cynicism and pessimism. Could hopepunk be the perfect antidote?

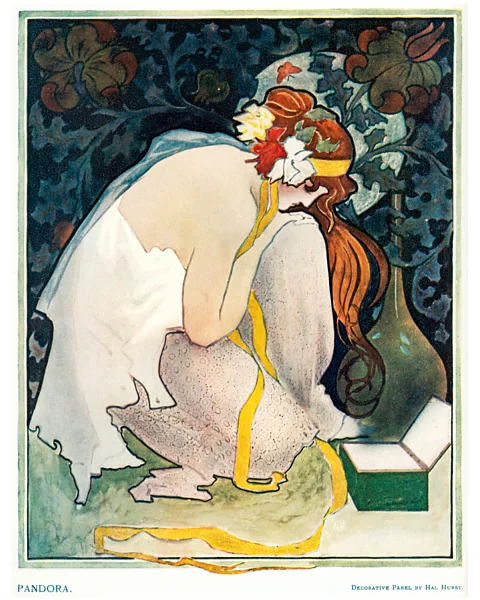

If you feel wary of optimism, you are far from alone. Writers and philosophers across human history have had ambivalent views of hope. These contradictory opinions can be seen in the often opposing interpretations of the Pandora myth, first recorded by Hesiod around 700 BC. In his poem Works and Days, Hesiod describes how Zeus created Pandora as a punishment to humanity, following Prometheus's theft of fire. She comes to humanity bearing a jar containing "countless plagues" – and, opening the lid, releases its evils to the world. "Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within the rim of the great jar," Hesiod tells us.

Alamy

AlamyThis is often interpreted as a metaphor for the emotion's potential to comfort us against the misery and duress that are inherent in the human condition. It sees hope as the sustaining force that Emily Dickinson would describe, thousands of years later, as the "thing with feathers – /that perches in the soul –".

It is possible to take a more pessimistic reading of the Pandora myth, however. Doesn't hope's presence in the jar, for example, suggest that it is some form of evil in itself? Perhaps Hesiod was hinting at the possibility that the supposedly soothing emotion can itself do harm.

The 19th-Century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was of this opinion. In Human, All Too Human (1878), he suggests that Pandora kept hope aside so that humanity would persist in living, despite the suffering that life inevitably entails. "Now man has the lucky jar in his house forever and thinks the world of the treasure. It is at his service; he reaches for it when he fancies it," he wrote. "Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man's torment."

Nietzsche's interpretation of the Pandora myth recalls Arthur Schopenhauer's descriptions of hope as "a folly of the heart". For him, hope is a delusion. In his essay Psychological Remarks (1851), he notes that the emotion "deranges the intellect's appreciation of probability" so that we neglect the likely outcomes of events, even when the odds are stacked against us. "A hopeless misfortune is like a quick death blow, whilst a hope that is always frustrated and constantly revived resembles a kind of slow death by prolonged torture."

The hopepunk rebellion

When explaining the origins of the term hopepunk, Rowland fully recognises the need to acknowledge human frailty and suffering – as seen in series like Game of Thrones. But they felt that it should be balanced with a recognition of our capacity to do good, and the possibility of positive change.

"Hopepunk says that kindness and softness doesn't equal weakness, and that in this world of brutal cynicism and nihilism, being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion," Rowland wrote in a follow-up to the original viral post. "It's about DEMANDING a better, kinder world." If hope sings a "tune without words" – as Dickinson described – then Rowland hears that song as a battle cry. This is the "punk" side of the moniker.

The essence of the hopepunk philosophy can be found in an exchange between Frodo and Samwise Gamgee in The Two Towers from Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films, as they struggle against the forces of evil around them.

"It's like in the great stories, Mr Frodo," Sam says. "Full of darkness and danger they were. And sometimes you didn't want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it's only a ing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must . A new day will come. And when the Sun shines it will shine out the clearer."

"What are we holding on to, Sam">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });