What Bond villains tell us about the world we live in

Alamy

AlamyIn the lead up to the long-awaited release of No Time to Die, Nicholas Barber charts the history of 007's colourful adversaries – what do they reveal ?

James Bond's creator, Ian Fleming, wanted his hero to be "an anonymous blunt instrument... with the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find". Bond's enemies would be a different matter. Beginning with Le Chiffre in Casino Royale, they had punning names, exotic backgrounds, distinctive physical characteristics, and the unfortunate habit of telling people all about their fabulously impractical schemes. Then, when they jumped from the page to the screen, they became even more colourful, hence the term "Bond villain" is now synonymous with cavernous, high-tech headquarters and manic threats ("No, Mr Bond, I expect you to die!") which are destined to be quoted as long as pubs exist. However far-fetched these characters may be, though, they are never completely separate from reality. There is always a thread that connects them to whatever audiences are worrying about, or to whichever other films they are watching. Drugs, social media, nuclear missiles... put any of these in a Nehru-collar tunic and you've got yourself a Bond villain.

More like this:

Alamy

AlamyThe "Soviet"

Rosa Klebb (Lotte Lenya), From Russia with Love, 1963

Squat, scowling, fond of frumpy military uniforms and clumpy, sensible shoes with built-in poison-coated blades, the main antagonist in From Russia with Love was a jingoistic caricature of women behind the Iron Curtain. The twist is that Rosa Klebb wasn't actually working for the Soviets. In Fleming's original novel she was an officer of Smersh, the Kremlin's most brutal secret service. But the films' producers didn't want their series to be too political, and so, on screen, all of Smersh's operatives worked instead for an independent terrorist organisation, SPECTRE. Klebb is the classic example of this sneaky revisionism: depending on your sympathies, you could view her either as a stereotypically dour and callous Soviet, or you could claim that she wasn’t a proper Soviet at all.

Alamy

AlamyThe Nuclear Threat

Auric Goldfinger (Gerte Fröbe), Goldfinger, 1964

In Fleming's novel, Auric Goldfinger hoped to spirit away every bar of gold in Fort Knox. The screen adaptation is largely faithful, but Goldfinger's amended plan was not to steal the gold, but to irradiate it with a dirty bomb, thus rendering it unusable. As well as being far cleverer, this plan chimed with the audience's fear of atomic weapons: Stanley Kubrick's arms-race farce, Dr Strangelove, came out in the same year. Subsequent Bond moves visualised other threats to civilisation (solar-powered death rays, killer viruses), but the one which recurred most often was that an atom bomb would fall into the wrong hands. The makers of Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, Octopussy, and The World is Not Enough all knew that nothing was more terrifying than a nuclear apocalypse, and nothing more reassuring than seeing a debonair secret agent prevent one.

Alamy

AlamyThe Spaceman

Sir Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale), Moonraker, 1979

In 1977, the closing credits of The Spy Who Loved Me announced that "James Bond Will Return in For Your Eyes Only". But the producers hadn't reckoned with another film that was in cinemas that year: Star Wars. Its phenomenal success meant that 007 had to go into space, so For Your Eyes Only was left on the launchpad and Moonraker blasted off instead: even if Fleming's source novel was earthbound, its title had enough of a futuristic ring to tempt Luke Skywalker fans. Not that the film was responding to Star Wars alone. In the real world, Nasa was developing its reusable Space Shuttle, and so the billionaire industrialist in Moonraker, Sir Hugo Drax, manufactured those very vessels. According to Peter Lamont, the film's visual-effects director, "Moonraker was meant to premiere in the week of the space shuttle's take-off. Unfortunately, they had engine trouble which put the programme back two years. So instead of being science fact, it was science fiction."

Alamy

AlamyThe Drug Lord

Franz Sanchez (Robert Davi), Licence to Kill, 1989

Created in the 1950s, 007 looked as if he might not make it through the 1980s. Stories about Russian spies seemed outdated at the tail end of the Cold War, and a new breed of laid-back US action hero made Bond himself seem like a stuffy anachronism. The series' producers' solution was to put him up against Franz Sanchez, a Latin-American drug lord. (Typically, they were tactful enough to say that he came from the fictional "Republic of Isthmus" rather than a real country). Sanchez was the kind of Scarface-alike who might have sneered at Mel Gibson, Bruce Willis or Eddie Murphy in one of their 1980s thrillers, or even at Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas on television's Miami Vice. He wasn't hell-bent on world domination, he just wanted to peddle cocaine. That was appropriate enough after a decade of Nancy Reagan's "Just Say No" campaigning, but if a Bond villain doesn't dream of incinerating a whole continent with a giant space bazooka, something's missing.

Alamy

AlamyThe Avenger

Alec Trevelyan (Sean Bean), GoldenEye, 1995

One of many Bond villains who are fractured mirror images of 007 (three others being From Russia with Love's "Red" Grant, Francisco Scaramanga from The Man with the Golden Gun and Skyfall's Raoul Silva), Alec Trevelyan was an MI6 agent – 006, no less – who switched sides because his parents had been Lienz Cossacks. Having fought with the Nazis against Russia in World War Two, the Cossacks surrendered to Britain. But "the British betrayed them, sent them back to Stalin, who promptly had them all shot". This repatriation, Bond acknowledged, was "not exactly our finest hour". Such issions of guilt became a theme after the Cold War, the implication being that British government officials – and British people in general – were in some way responsible for the trouble that befell them. In The World Is Not Enough, Elektra King blamed M for advising her father not to pay the ransom when she was kidnapped. In Skyfall, Raoul Silva (see below) blamed M for selling him out to the Chinese. And in Spectre, Blofeld blamed Bond for... well, being Bond (see below).

Alamy

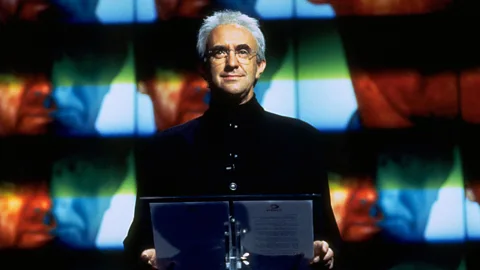

AlamyThe Tycoon

Elliot Carver (Jonathan Pryce), Tomorrow Never Dies, 1997

Diabolical criminal kingpins don't always lurk in hollowed out volcanoes; sometimes they strut around skyscrapers and high-society horse races. Bond villains who are also pillars of the establishment include Hugo Drax in Moonraker, Max Zorin in A View to a Kill, Gustav Graves in Die Another Day, and Dominic Greene in Quantum of Solace: suave and respectable entrepreneurs who throw swanky cocktail parties and rarely drop their guests into tanks stocked with hungry sharks. The most believable, and therefore most frightening, of the subset is Elliot Carver, a media mogul inspired by Rupert Murdoch and Robert Maxwell. Declaring that "words are the new weapons, satellites the new artillery", Carver (a British Bond villain, for once) was a pioneer in the field of fake news. He aimed to start a world war in exchange for "exclusive broadcasting rights in China for the next 100 years". But these days a super-rich businessman would never interfere with international politics in such a dastardly fashion. Would he?

Alamy

AlamyThe Cyber-Attacker

Raoul Silva / Tiago Rodriguez (Javier Bardem), Skyfall, 2012

Most Bond villains have a wall-sized computer or two, and Alan Cumming played a hacker in GoldenEye. But Skyfall was the film that zeroed in our anxieties about the internet. Sandwiched between the release of The Social Network (2010), which dramatised the birth of Facebook, and The Fifth Estate (2013), which dramatised the birth of WikiLeaks, the film co-starred Javier Bardem as Raoul Silva, a cyberterrorist who used to work for MI6. He attacked his former employers by posting the identities of MI6's current undercover agents on YouTube, so it was lucky that the good guys had their own IT boffin. The film's geeky young Q (Ben Whishaw) boasted to 007: "I'll hazard I can do more damage on my laptop sitting in my pyjamas before my first cup of Earl Grey than you can do in a year in the field." Is that supposed to be comforting?

Alamy

AlamyThe Family Member

Ernst Stavro Blofeld / Franz Oberha (Christoph Waltz), Spectre, 2015

The iconic SPECTRE boss is Bond's most enduring adversary, first as a shadowy, cat-stroking mastermind in From Russia with Love and Thunderball, and then as the central baddie in You Only Live Twice, On Her Majesty's Secret Service and Diamonds Are Forever. How disappointing, then, that when Blofeld returned to the franchise in Spectre, he revealed that he was Bond's foster brother, and that all of his evil machinations were a way of getting back at the boy who hogged his dad's attention. Talk about petty. This Austin Powers-alike retconning reduced 007's adventures from the political to the personal. Instead of being an anonymous blunt instrument, he was someone whose family squabbles resulted in global conspiracies. The change may have been in line with much of today's fanboy-ish pulp fiction, in which the plots are driven by the heroes' friends and relations, but it will be a relief if the next Bond villain, Safin (Rami Malek), yearns to take over the world for the sake of it, and not because he resents M or 007.

Love film and TV? BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.