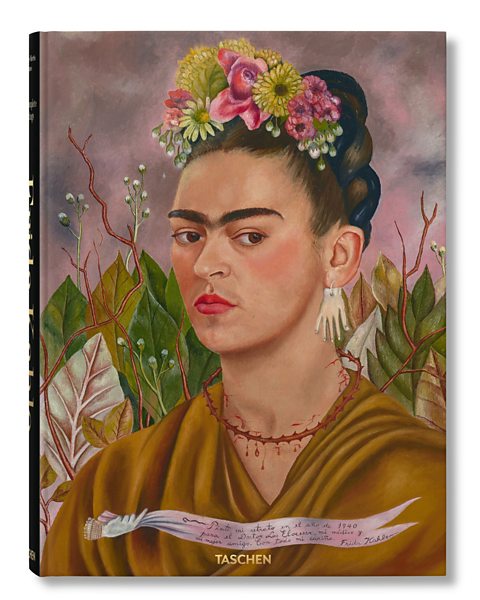

The unseen masterpieces of Frida Kahlo

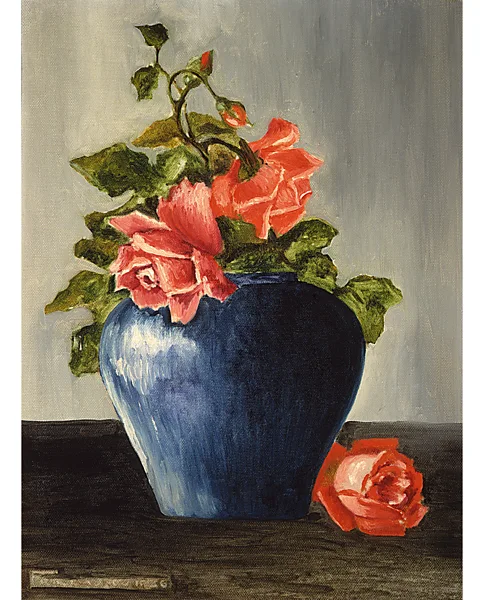

Private Collection, USA. Photo courtesy of Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art New York

Private Collection, USA. Photo courtesy of Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art New YorkLost or little-known works by the Mexican artist provide fresh insights on her life and work. Holly Williams explores the rarely seen art included in a new book of the complete paintings.

You know Frida Kahlo – of course you do. She is the most famous female artist of all time, and her image is instantly recognisable, and unavoidable. Kahlo can be found everywhere, on T-shirts and notebooks and mugs. While writing this piece, I spotted a selection of cutesy cartoon Kahlo merchandise in the window of a shop, maybe three minutes' walk from my home. I bet many readers are similarly in striking distance of some representation of her, with her monobrow and traditional Mexican clothing, her flowery headbands and red lipstick.

More like this:

Partly, this is because her own image was a major subject for Kahlo – around a third of her works were self-portraits. Although she died in 1954, her work still reads as bracingly fresh: her self-portraits speak volumes about identity, of the need to craft your own image and tell your own story. She paints herself looking out at the viewer: direct, fierce, challenging.

Taschen

TaschenAll of which means Kahlo can fit snugly into certain contemporary, feminist narratives – the strong independent woman, using herself as her subject, and unflinchingly exploring the complicated, messy, painful aspects of being female. Her paintings intensely represent dramatic elements of a dramatic life: a miscarriage, and being unable to have children; bodily pain (she was in a horrific crash at 18, and suffered physically all her life); great love (she had a tempestuous relationship with the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, as well as many other lovers, male and female, including Leon Trotsky), and great jealousy (Rivera cheated on her repeatedly, including with her own sister).

But thats not all they show – her art is not always just about her life, although you could be forgiven for assuming it was. Books are written about her trauma, her love life; she's been the subject of a Hollywood movie starring Salma Hayek. Kahlo has become a bankable blockbuster topic, guaranteed to get visitors through the door of galleries, even if what they see is often more about the woman than her art.

But what about her work? For some art historians, the relentless focus on the person rather than the output has become tiresome, which is why a new, monumental book – Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings – has just been published by Taschen, offering for the first time a survey of her entire oeuvre. Mexican art historian Luis-Martín Lozano, working with Andrea Kettenmann and Marina Vázquez Ramos, provides notes on every single Kahlo work we have images of – 152 in total, including many lost works we only know from photographs.

Speaking to Lozano on a video call from Mexico City, I ask if a comprehensive survey of her work is overdue, despite there being so many shows about her all over the world?

"As an art historian, my main interest in Kahlo has been in her work as an artist. If this had been the main concern of most projects in recent decades, maybe I would say this book has no reason to be. But the truth is, it hasn't," he says. "Most people at exhibitions, they're interested in her personality – who she is, how she dressed, who does she go to bed with, her lovers, her story."

Because of this, exhibitions and their catalogues have often focused on that story, and tend to "repeat the same paintings, and the same ideas about the same paintings. They leave aside a whole bunch of works," says Lozano. Books also re-tread the same ground: "You repeat the same things, and it will sell – because everything about Kahlo sells. It's unfortunate to say, but she's become a merchandise. But this explains why [exhibitions and books] don't go beyond this – because they don't need to."

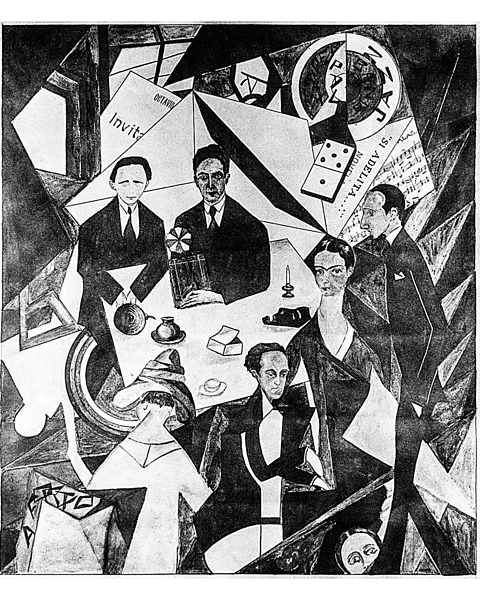

Rafael Doniz/ photo by Guillermo Kahlo

Rafael Doniz/ photo by Guillermo KahloThe result is that certain mistakes get made – paintings mis-titled, mis-dated, or the same poor-quality, off-colour photographs reproduced. But it also means that ideas about what her works mean get repeated ad infinitum. "The interpretation level becomes contaminated," suggests Lozano. "All they say about the paintings, over and over, is 'oh it's because she loved Rivera', 'because she couldn't have a kid', 'because she's in the hospital'. In some cases, it is true – but there's so much more to it than that."

The number of paintings – 152 – is not an enormous body of work for a major artist. And yet, astonishingly, some of these havenever been written about before: "never, not a single sentence!" laughs Lozano. "It's kind of a mess, in of art history."

Offering a comprehensive survey of her work means bringing together lost or little-known works, including those that have come to light in auctions in the past decade or so, and others that are rarely loaned by private collectors and so have remained obscure. Lozano hopes to open up our understanding of Kahlo. "First of all – who was she as an artist? What did she think of her own work? What did she want to achieve as an artist? And what do these paintings mean by themselves">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });