The Ghent altarpiece: An unlikely fruit meaning original sin

Alamy

AlamyVan Eyck's Ghent altarpiece features a surprising candidate for the forbidden fruit. Kelly Grovier explores how it gives spiritual coherence to the 15th-Century work.

Great works of art contain seeds of strangeness from which their meaning endlessly emerges. Some of these seeds are impossibly famous: the twisting fingers of foam that tickle the breaking crest of Hokusai's Great Wave; the vibrating whorls of astral heat in Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night; the weightless orb dangling from the lobe of Johannes Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring. Some are yet to be uncovered. In the case of the exquisite 15th-Century altarpiece designed by the Flemish artist Hubert van Eyck and painted by his brother Jan for Saint Bavo's Cathedral chapel in Ghent – the widely revered polyptych known as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb – a juicy detail at the very heart of the work has been waiting to be plucked and squeezed into significance for more than 600 years.

Look closely at the dozen s that comprise the interior of the altarpiece when it is swung open wide on its many hinges, and there, at the epicentre of the work, you will find a strangely citrus semi-circular sun, with a heavy yellow outer rind surrounding a thick inner white pith. This wedge is carefully positioned at a pivot point in the work, between the upper and lower s of the altarpiece, and shoots from its core sharp streams of luscious light. Once spotted, this citric semi-sphere, in which the Holy Spirit, assuming the shape of a dove, has been squeezed in, is recognised as the source of dazzling resplendence in the work – the engine of glory that spills on everything. It even seems to splash off the head of the pedestaled lamb that is the focus of the ritual below.

In order to appreciate fully why a slice of citrus fruit, unexpectedly masquerading as a radiating sun, has symbolically been inserted at the epicentre of the masterpiece – how it, and it alone, gives spiritual coherence to the work and transforms it from being a jaunty jumble of flashy textures to a deeper meditation on the wonders of salvation – we must first remind ourselves of the broader structure and religious strategy of the altarpiece. Treasured for its exceptionally realistic depiction of objects and figures magicked from oil paint (a medium that had only recently entered into wider practice in Europe), the Ghent altarpiece was commissioned by the wealthy Flemish merchant Jodocus Vijd and his wife Lysbette in the 1420s to adorn a newly constructed chapel in Saint Bavo's Cathedral. A marvel in the history of image-making, the altarpiece is comprised of some 24 oil-on-wood s, 12 of which are visible when the altarpiece is closed, 12 when opened.

Alamy

AlamyThe complex work is best known for its vision of a majestically enthroned Christ flanked by a flamboyant Virgin Mary (to our left) pursuing a girdle book, and, on the other side, by a flashy St John the Baptist in a swanky green cape. Beneath the extravagant triumvirate (known as the Deisis in earlier Byzantine art), a panorama of pastoral s captures in mid stride an immortal pilgrimage of countless prophets and apostles, hermits and philosophers, sinners and saints, as it descends down the ages from the Old Testament to the present to congregate around the 'Lamb of God' – an allegorical designation for Christ from the Gospel of John – which is hoisted atop an altar, basking in adoration.

The virtuosity of Van Eyck's astonishing brushwork, which miraculously spins from pigment and oil this engrossing gallimaufry of competing glimmers and shimmers – of golden brocades and bejewelled crowns, spangled vestments and ornate clasps – is thrilling to behold. Never before has paint sung so enchantingly. Our eye flits with surprising impunity from the lavish velvet folds of the Virgin Mary's ultramarine robe to the glint of precious stones that adorn an angel in a choir nearby, from the glisten of polished armour worn by a galloping knight to the sheen of silver censors swinging before the altar.

Alamy

AlamyIn theological , Van Eyk's vision of a worldly realm not merely redeemed but utterly exalted, cleansed of sin and chrysalised into piety, is the dazzling culmination of the so-called 'felix culpa', or 'fortunate fall' of mankind. The many miracles that the altarpiece celebrates – from Christ's conception within the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation, depicted on the outer s, to his subsequent birth, sacrifice, resurrection, and salvation of mankind – are all ramifications of the ancient transgression committed by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, when the pair ate from the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Without the commission of that initial crime described in Genesis, none of the intoxicating spiritual grandeur or dizzying material magnificence that Van Eyk's brush describes would be possible.

Once bitten, twice shy

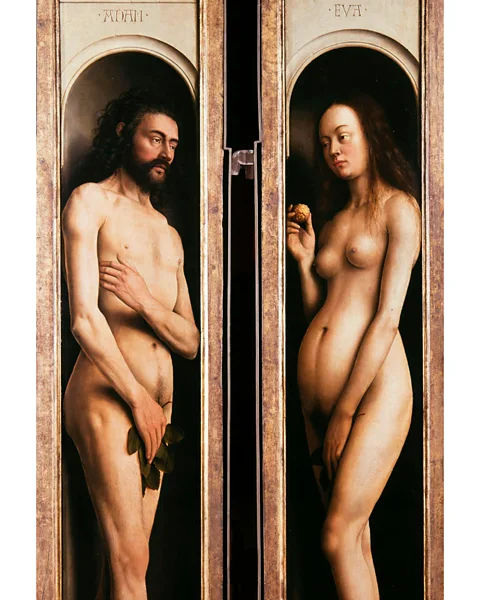

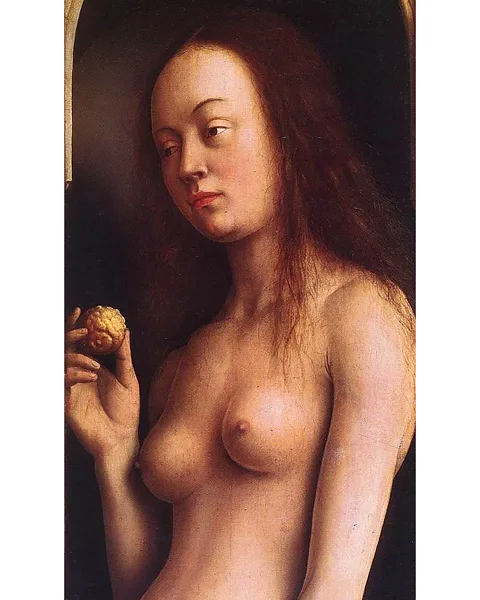

But there's a problem. It is evident from Van Eyk's own depiction of Eve in the near-life-sized portrait of her to the right of the majestic enthronement of Christ (and mirrored, on the left, by a corresponding portrait of Adam), that she has not yet committed the sin she is known for. Though everything about her doleful deportment and pathetic pallor may imply that she is in a state of shamefaced punishment and exile, the fruit that she holds in her hand is still unmistakably integral, unbitten, and uneaten. The scriptural age from Genesis that sanctions Eve's portrayal makes abundantly clear that it is not the desiring, plucking, or holding of the forbidden fruit that precipitates the fall, but the eating of it: 'And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.'

Alamy

AlamyLook closely at the piece of fruit that teeters on the tips of Eve's lugubrious fingers and it is clear that it has not been bitten into. Less clear, however, is what that fruit actually is. Too small and bumpy to be an apple, this curious rondure does not resemble a pomegranate either, or a fig, or a pear – each of which has been auditioned by biblical scholars as possible candidates for the forbidden fruit. In 1976, the medieval scholar James Snyder made an irrefutable case for the fruit as being "a distinct citrus variety", explaining that "although the original name is no longer a familiar one, it was well known in the 15th Century and would have been a most appropriate example in Van Eyck's time of the exotic fruit of Paradise that Eve offered her husband: a type of citrus known as the 'Adam's Apple'". Known more commonly today as a citron – or an "etrog", among observers of the Jewish holiday Sukkot (The Feast of Tabernacles) in which the fruit is ceremonially waved in a bundle that contains a frond of a date palm, a myrtle bough, and a willow branch. The citron/etrog is thought to be an early precursor, pre-hybridisation, of the many citrus varieties we enjoy today.

We can be certain that Van Eyck was not cavalier in deciding what fruit to hand Eve. He was obsessed with the spiritual language of plants and flowers. From the triple-leaf clovers that carpet the foreground of the lower (echoing the trinity) to the purity of lily petals trumpeting from Mary's crown, he was alive to the emblematic potential of every stem and blade that he has planted in his painting. But the deeper significance of the citron is surprisingly elusive. The fact that, since antiquity, it has been prized for its sweet scent, seems unremarkable. That Romans may have added its essence to perfume and attached healing power to its flesh, could be said of many other botanical entities as well. Given the swell of Eve's stomach, it is tempting to think that an obscure folk preventative for difficult childbirth, requiring pregnant women eat the tip of the fruit, might edge us closer to something significant. But that custom, it seems, likely belongs to the lore of a later era and was probably not what Van Eyck would have had in mind.

Whatever its concealed cultural connotations, the citron is endowed with a glistening inner architecture that Van Eyck would doubtless have found appealing. The lucency of its solar structure when sliced, and the juice geometry of its fragrant flesh, belie the crude coarseness of its exterior. It alone among the nominees for forbidden fruit can generate a substance equivalent to light. Though the citron that Eve holds in her hand may be eternally intact, Van Eyck has ingeniously inserted another at the very centre of his painting, one that we cut into and violate each and every time that we open the s of his altarpiece. Once recognised for its resemblance to the cross-section of a citron, with its characteristically thick white pith (or, more correctly, albedo), that strange citric sun at the heart of Van Eyck’s painting zests itself into pictorial pertinence. By doing so, the artist has ensured that we participate in the transgression that triggers the fortunate fall necessary for the narrative of his work to work. Remove the severed citron from the heart of his masterpiece and the altarpiece's entire theological logic breaks down. The grandeur it celebrates is diminished to a non sequitur. The light goes out.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.