Pulp’s Different Class: The album that defined an era

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s 25 years since the release of Pulp’s Different Class. The album’s stories of class division, illegal raves and uncertain futures reflect Britain then – and now, writes Clare Thorp.

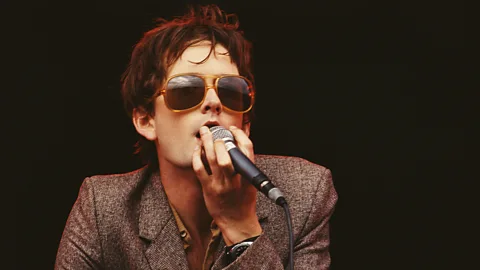

There aren’t many albums that state their intent as clearly as Pulp’s Different Class. “We’re making a move, we’re making it now, we’re coming out of the sidelines,” sings Jarvis Cocker on opener Misshapes, both a call to arms for fellow misfits and a manifesto for the band themselves. “Brothers, sisters can’t you see? The future’s made for you and me.” It was a bold claim, by a band who knew their time had, finally, come.

When Pulp released Different Class in October 1995, it was at the peak of the Britpop era – less a cultural movement and more a label the music press had slapped on a collection of disparate (though mostly white, guitar-based) British bands infiltrating the charts in the mid-90s. What started as a celebration of the British music industry reasserting its influence after a few years dominated by the US grunge scene had morphed into something of a media bandwagon.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe year had already seen UK number one albums by Elastica, Supergrass, The Charlatans, Black Grape and The Boo Radleys. By that summer Britpop had reached – depending on your point of view – either its apex or nadir, when Blur and Oasis were involved in a chart battle that dominated newspapers and made the BBC’s Six O’Clock News. Blur won that first round and released their fifth album, The Great Escape, a few weeks later. Oasis followed with (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, which would go on to become the biggest-selling record of the decade in the UK (thus ultimately winning the ‘war’ with their rivals).

Sign of the times

The best, though, was still to come. Pulp had no interest in the Britpop tag (“It still makes me shudder a bit today,” drummer Nick Banks tells BBC Culture) – yet 25 years on, its Different Class not only feels like the most enduring snapshot of a mid-90s Britain on the cusp of a New (Labour) era, coming down from the acid-house boom and looking ahead to the millennium – but, with its tales of illegal raves, class divisions and uncertain futures – still feels the most relevant today.

To a casual music fan, it might have felt like Pulp appeared out of nowhere in 1995 – when within the space of weeks their single Common People hit number two in the charts, they played a triumphant Glastonbury headline set and frontman Jarvis Cocker became an unlikely tabloid fixture. It had actually been almost two decades in the making. Cocker formed the band in Sheffield in 1978, when he was just 15 years old. In The Pulp Masterplan – a statement written in an exercise book when he was a teenager and which he revealed this summer in The Big Issue, he wrote: “The group shall work its way into the public eye by producing fairly conventional, yet slightly offbeat, pop songs. After gaining a well-known and commercially successful status, the group can then begin to subvert and restructure both the music business and music itself.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOriginally called Arabicus, then Arabicus Pulp, then just Pulp, the band went through several line-up changes and spent more than a decade in obscurity before starting to garner attention in the early 90s. By then they were made up of Cocker (vocals), Russell Senior (guitar, violin), Candida Doyle (keyboards), Nick Banks (drums) and Steve Mackey (bass). In 1994, Pulp’s fourth album, His ’n’ Hers, reached number nine in the charts, got them their first top 40 single (Do You the First Time?) and landed a Mercury Music Prize nomination.

Then in 1995 the success of Common People, swiftly followed by the last-minute call from Glastonbury, changed everything. Recalling that Saturday night headline slot, Nick Banks says: “I don’t think I even looked up from the drums until near the end because I was so scared of cocking a song up or doing something wrong. But by the time we got to Common People, the sound of the crowd singing along was so loud. I just looking out and screaming to myself. It was so amazing.”

When the band went back into the studio to finish recording their fifth album, it was with the knowledge that they finally had the captive audience they’d waited so long for. “We felt that the next record was our chance, it was our time, it was our springboard into the public’s consciousness, a chance to reach out to those people who hadn’t cottoned on to us yet,” says Banks. “Pulp had been on the margins for so long. The idea that finally we were going to be exposed to a greater audience was a delicious sort of feeling.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMuch of the writing for the record took place above a pottery warehouse owned by Banks’ family. “We would set homework, where you’d have to come to the next rehearsal with some song idea – a word, a bit of a tune, a phrase, a scenario, anything,” says Banks. “We’d swap instruments so that no one was getting too big for their boots. It was a great time of everyone being together and having input. And, you know, thinking that we were on the cusp of something.”

As on His ’n’ Hers before, Different Class saw Cocker return to one of his favourite subjects, sex, on songs like Underwear and Pencil Skirt. But his observations also moved out of the bedroom to focus on the class divide, something that he and other band had become increasingly aware of.

“You really did notice it in London, certainly for us folks coming down from Sheffield,” says Banks.

“You get invited to some daft party and meet someone who was The Count of Monte Cristo’s son or something like that. You didn’t meet them in Rotherham, that’s for sure.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs part of the chart ‘battle’ between Blur and Oasis, those two bands had seen not only their songs pitted against one another, but their class, often in the simplest and most patronising of ways. Oasis were the northern working-class lads who loved drinking beer and getting into scrapes. Blur were the middle-class art-school southerners whose lyrics quoted Balzac.

That these two versions of UK life were the only ones presented itself showed an inherent problem with Britpop. Speaking recently on the Adam Buxton podcast, writer Zadie Smith said: “Blur v Oasis, that whole scene… it had no idea what was going on in black music, in Asian music. It was just oblivious. And if you were going to participate in the spirit of the 90s, you had to participate in that – in music that often you had no interest in or knowledge of, that often had nothing to do with the way you’d grown up, the records in your house.”

Common people

Meanwhile Pulp – who confused those stoking the pantomime class war by having that managed to be both northern, working class and go to art school in London – were too busy writing about class wars to participate in them.

On Common People Cocker tore into class tourists, inspired by a well-to-do Greek girl he met at Central Saint Martins who wanted to try slumming it in Hackney for a while – “smoke some fags and play some pool, pretend she never went to school”. Hidden underneath those irresistible pop hooks is a mounting anger not just at her but all those who co-opt a working-class identity as a shortcut to authenticity – without ever dealing with the fear, uncertainty and absence of choice that comes with having no money. Towards the end of the song Cocker is practically spitting. “You will never understand how it feels to live your life with no meaning or control, and with nowhere left to go”.

His anger is even more palpable on I Spy, a song in which someone who has nothing observes those who have everything – all the while plotting how to “blow [their] paradise away”. While fantasising about how he’ll infiltrate this Ladbroke Grove life, he compares his own: “My favourite parks are car parks. Grass is something you smoke, birds are something you shag. Take your Year in Provence and shove it up your ass.”

But if a young Cocker thought the odds were stacked against him in the 80s and early 90s, he’d be even more raging now. Class privilege – especially in the arts – has only worsened. Last year, research by Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission found that 20% of British pop stars were privately educated (compared with 7% of the general population). Figures from 2018 showed that just 44% of the intake at the Royal Academy of Music came from state schools, with the Courtauld Institute of Art only slightly better at 55%. “A bunch of young working-class kids from the north really storming into the charts and onto the front pages of the papers… back in the 90s it was hard,” says Banks. “It seems almost impossible now.”

Pulp had spent most of their lives on the outside looking in, making them the perfect champion of the disempowered. “Being able to observe without being observed yourself, you get to see the real sort of underbelly or workings of what goes off in life,” says Banks.

No detail ed Cocker by, from “the broken handle on the third drawer down of the dressing table” (F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E) to the “woodchip on the wall” in Disco 2000. His stories were specific, but reflected a wider society, too – as in Sorted for E’s and Whizz, a song inspired by Cocker attending raves in the late 80s. “Is this the way they say the future’s meant to feel, or just 20,000 people standing in a field?” With illegal raves now on the rise again in the UK, he could easily be talking about 2020, not 1988. In fact, aside from calls to “meet up in the year 2000”, so much of the album and its themes of being young and out of options feels pertinent in the current day.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe album reached number one and went on to win the Mercury Music Prize. A sell-out arena tour followed. Pulp were no longer the outsiders. It felt good – to begin with, at least. “When you’ve been in the desert so long and you reach the oasis you jump in and fill your boots,” says Banks.

Cocker had achieved his lifetime ambition to be a pop star – but he would later liken it to “a nut allergy”. The infamous 1996 Brit Awards, where he ran onstage during Michael Jackson’s performance of Earth Song to wiggle his bum to the audience – and ended up getting arrested on suspicion of assault (it was video footage captured by David Bowie’s team that got him off the hook) – turned the dream of pop stardom into a nightmare. Speaking recently to the New York Times he said: “In the UK, suddenly, I was crazily recognised and I couldn’t go out anymore. It tipped me into a level of celebrity I couldn’t ever have known existed, and wasn’t equipped for. It had a massive, generally detrimental effect on my mental health.”

His disillusionment – repulsion, even – with fame, played out on Pulp’s next album, This Is Hardcore, a record about “panic attacks, pornography, fear of death and getting old.” On opener The Fear, he sang: “This is the sound of someone losing the plot/Making out they’re OK when they are not”. If Britpop was already halfway out the door, this album gave it one last brutal kick to see it on its way.

“At the time we just laughed at [Britpop],” says Banks. “We’d been lumped in with many, many scenes over the years. We just couldn't relate to it, we weren’t bothered and the nearest we were to Britpop was Russell [Senior] wearing some Union Jack socks. It was always labels that other people foisted upon us.”

After releasing their seventh album, the Scott Walker-produced We Love Life, in 2001, Pulp went on hiatus for a decade, reforming in 2011 for a series of live dates. They played their last gig – for now at least – in their hometown of Sheffield in December 2013.

Cocker now has a new band, Jarv Is…, who released their first album Beyond the Pale over the summer. One track, House Music All Night Long, has proved something of a lockdown anthem, featuring the lyrics: “Saturday night, cabin fever in house nation/This is one nation under a roof/ Ain’t that the truth/Goddamn this claustrophobia/’Cause I should be disrobing you.” It was recorded before the pandemic, but – even when it’s accidental – it seems Pulp’s frontman can’t help writing records that perfectly capture a moment in time.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.