Fashion photography's reluctant poster boy

When is a fashion or beauty image art? Cath Pound explores the remarkable work of the legendary artist whose ‘strangeness’ raised the status of the medium.

The name Man Ray springs instantly to mind when considering the most innovative photographers of the 20th Century. His rediscovery of the techniques of Solarisation and Rayography and his inventive use of close cropping resulted in some of the most iconic images ever produced in the medium. But it is often forgotten that for two decades he worked almost exclusively as a fashion photographer. Although dismissive of this work, which he saw primarily as a way to fund other artistic endeavours, his ground-breaking compositions for the likes of Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar transformed a previously staid and rigid format into an artform – and produced images that, removed from their original context, have become legendary.

More like this:

In the early decades of the 20th Century, fashion photography was practised by only a small number of specialists who frequently found it challenging to compete with the illustrators who dominated the fashion press of the era. “Reproducing photographs was still very difficult and expensive at the time,” explains Catherine Örmen, co-curator of an exhibition on Ray’s fashion photography at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. In addition, illustration could neatly portray a trend, and reproduce details that the technical limitations of printing photographs in magazines made problematic.

Alamy

AlamyRay’s entry into this rarefied world came almost by accident. He moved to Paris in 1921 to mingle with the Dada and Surrealist circles there, but the failure of his first solo exhibition created an urgent need to make money. The art critic and writer Gabrièle Buffet-Picabia introduced him to the fashion designer Paul Poiret, who was looking for original images that could highlight the human element which illustration lacked.

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. Rmn-Grand Palais / Guy Carrard/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. Rmn-Grand Palais / Guy Carrard/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020These early attempts prove that Ray was far from mastering his subject – he freely itted to knowing nothing about the genre, and proved unable to light a model correctly. However, an image of Poiret’s wife, Denise, reflected in a mirror with her hand on a Brancusi statue is an early indication of Ray’s professed desire to merge fashion with art. It was also while developing photographs for Poiret that Ray inadvertently stumbled across the process he dubbed Rayography. Although first discovered in the 19th Century, the technique – placing an object on photographic paper which is then exposed to a light source – was not commonly used. Ray made it his own, with the dramatic contrast of light and dark becoming central to his work. The images caught the eye of editors at Vanity Fair, who ran a four-page series of them in their November 1922 issue.

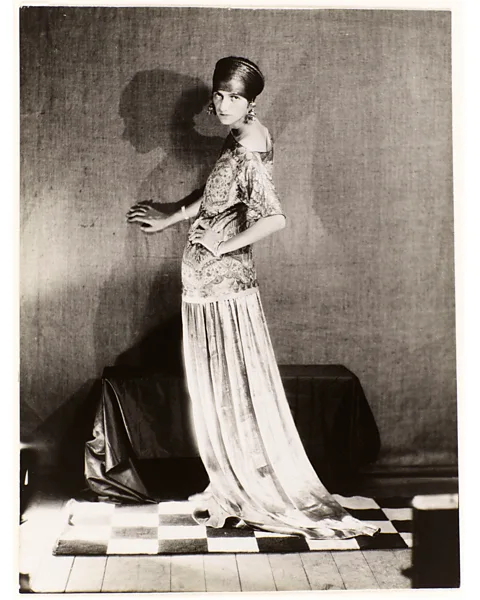

Ray’s artistic connections soon allowed him to become the fashion photographer of choice in the 1920s, with filmmaker and writer Jean Cocteau introducing him to everyone who was anyone. He regularly photographed society figures for Vogue, and in 1924 produced a striking image of US heiress Peggy Guggenheim exuding oriental opulence in a typically decadent Poiret creation.

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020Although his early work was often indistinguishable from other photographers at Vogue, he was already experimenting with enlarging his portraits. “This enlargement creates blurring effects and allows the grain of the photomechanical grid to appear clearly visible, which is typical of Man Ray’s photographs,” says co-curator Maud Marron-Wojewodzki. His desire for experimentation also led him to produce images such as Noire et Blanche (Black and White), which first appeared in a May 1926 edition of Vogue. The pale, elongated face of his then lover, Kiki de Montparnasse, is juxtaposed with an African ceremonial mask in an image that references Surrealist ideas of the unconscious and the photographic process itself.

Stranger things

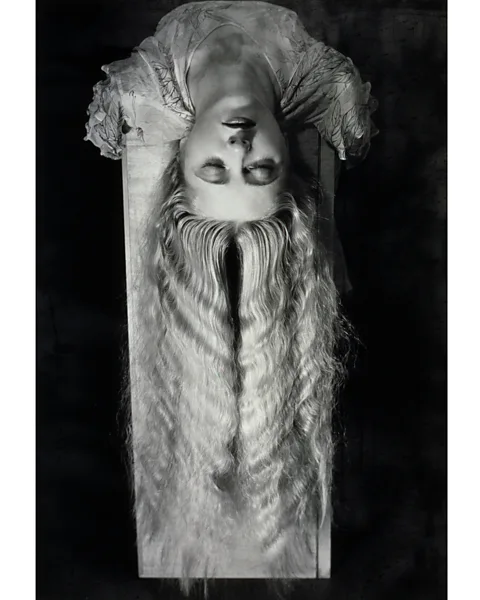

As Ray honed his craft throughout the decade, the circles he moved in had an increasing stylistic impact on his work. Dada and Surrealism gave him the freedom “to invent a form of expression all his own which consisted mainly of distancing himself from the reality of the model he had to photograph,” says Örmen. “He cultivates a taste for fetishism in his images – photographs of feet are numerous, and accessories play a leading role,” adds Marron-Wojewodzki, who also notes his fascination with wax mannequins and an element of “disturbing Freudian strangeness” throughout his fashion photography.

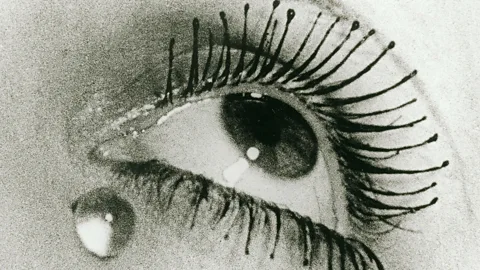

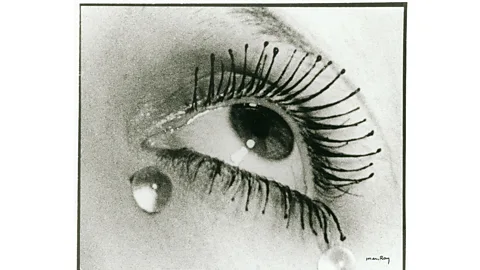

Alamy

AlamyThis is often particularly evident in his advertising work. Disembodied hands are a regular feature and he constantly uses cropping to remove the image from reality. The most famous example of this is Larmes (Tears), from around 1932. Originally a photograph of the entire, forlorn-looking face of a model with glass tears dotted across her cheeks, Ray cropped the composition to two eyes and a nose, the format in which it would appear as an advert for Cosmècil Mascara in 1935.

Larmes was produced at around the time of Ray’s break-up from Lee Miller and may well have been a response to that. Miller had arrived in Paris in 1929 to work as a fashion model, and immediately sought out Ray to announce she was going to be his photographic assistant. Legend has it that it was Miller who inadvertently re-discovered the technique of Solarisation when, having felt a mouse run across her foot, she instinctively turned on a light in the darkroom, exposing the photographs in development. Previously seen as nothing more than a dark-room accident, the technique – which renders part of the image negative and part positive, to create images with a magical, dreamlike aura – was perfected by Ray and Miller.

Galliera/ Parisienne de Photographie/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020

Galliera/ Parisienne de Photographie/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020Ray brought this technique, and the many others he had developed over the previous decade, to Harper’s Bazaar, which he began working for in 1934. Here he was truly able to reconcile commercial constraints with a desire for originality, helped in no small part by the uniquely creative environment he was entering. Editor-in-chief Carmel Snow and artistic director Alexey Brodovitch were keen to raise the status of photography, and Ray’s technical innovations combined perfectly with Brodovitch’s desire to revolutionise the layout of the journal. The freedom he was given “allowed him to produce images bordering on abstraction which embodied the very essence of fashion”, says Örmen.

In startling compositions, Ray shows models in Schiaparelli reclining on white plinths as if they were sculptures or irreverently places a model in a sumptuous pleated silver gown by Madeleine Vionnet in a padded wheelbarrow. Elsewhere he overprinted images or shot multiple viewpoints to dramatically emphasise the movement of a dress. Artwork was frequently included in his compositions. Models were positioned in front of birds by Giacometti, and Man Ray’s own painting of Lee Miller’s lips, A L’heure de l’observatoire – Les Amoureux (Observatory Time – The Lovers) (1936), derived from a 1930 photograph, appeared as a backdrop to a spread in 1936 in which a reclining model reached her hand up.

Courtesy Fondazione Marconi/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020

Courtesy Fondazione Marconi/ Man Ray 2015 Trust/ Adagp, Paris 2020But just as he was hitting his creative peak, Ray turned his back on fashion photography. When the outbreak of World War Two necessitated a return to the US he abandoned it completely, fearing his commercial reputation was beginning to erase his artistic one. Despite his indifference, Ray’s ground-breaking techniques and innovative compositions undoubtedly raised the status of fashion photography to an artform, and images including Larmes and Noire et Blanche have become icons of 20th-Century photography.

Man Ray and Fashion is at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, until 17 January 2021.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.