How One Hundred Years of Solitude redefined Latin America

Rebecca Hendin

Rebecca HendinWhen Gabriel García Márquez wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude, he reimagined the genesis of his continent. That had real political impact, writes Felipe Restrepo Pombo.

Before One Hundred Years of Solitude, Latin America bore certain similarities to the imaginary place described in the first paragraph of the novel: “The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point”. The continent, obviously, wasn’t a new place when Gabriel García Márquez wrote his acclaimed novel: the authors known as Cronistas de Indias, during the 15th and 16th Centuries, undertook the task of describing the land; they named unknown things while seeing them for the first time.

Many decades later, García Márquez embarked on a second Discovery of America. From his little studio in Mexico City, patiently composing on his typewriter, he reimagined the genesis of the continent and by doing so changed its future forever.

More like this:

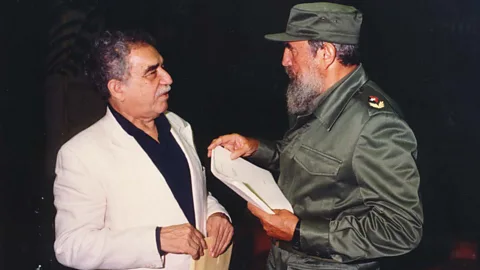

During the second half of the 20th Century, Latin America went through a convulsive period. Some countries – such as Chile, Colombia and Mexico – were struggling with instability, dictatorships, and political violence. This led to abrupt and, for the most part, confusing social changes, including the Cuban Revolution, led by Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro.

Alamy

AlamyWhen García Márquez was in the first stages of his immense saga, he became fascinated with the turn of events in Cuba. What struck him the most was the real possibility of a new order for countries in this hemisphere, far from the pressure and demands of the United States. Many intellectuals – Mario Vargas Llosa, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir, among many others – shared García Márquez’s enthusiasm. However, in the ensuing years, most of them grew disappointed and distanced themselves from the Cuban model. But it’s undeniable that the revolution had a major impact on the tone of One Hundred Years of Solitude: it gave García Marquez hope for the fate of Latin America.

Weaving an epic

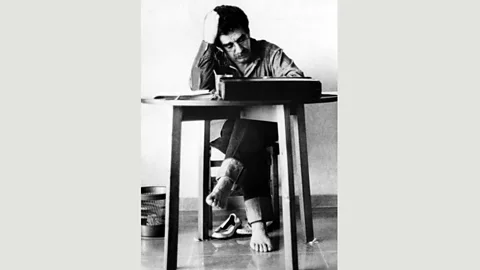

Writing his masterpiece, nevertheless, wasn’t easy. At the time, he was living with Mercedes, his wife, and his two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, in Mexico City. They had fled Colombia because García Márquez didn’t feel at ease with the right-wing government in his country. He was living abroad – before settling in Mexico City he spent time in Caracas, Paris and Barcelona – all while nurturing his ambition to become a world-renowned novelist. But the family struggled to survive on his low wage as an international correspondent for a number of Spanish-language magazines and newspapers. His previous books had been highly praised yet a commercial failure. García Márquez knew he had a great story, but he just couldn’t find the right path for the epic novel he had in mind.

Alamy

AlamyThere are many legends – which, throughout the course of his life, he never bothered to confirm or deny – about how he found inspiration and overcame the writer’s block that plagued him. I choose to believe the version I read in Gerald Martin’s wonderful biography: “He set out with his family for a beach vacation in Acapulco, a day’s drive south. Partway there, he stopped the car – a white 1962 Opel with a red interior – and turned back. His next work of fiction had come to him all at once. For two decades he had been pulling and prodding at the tale of a large family in a small village. Now he could envision it with the clarity of a man who, standing before a firing squad, saw his whole life in a single moment.”

According to Martin, Mercedes immediately cancelled the relaxing weekend away. They drove back to their house, and she told him to start writing. She would take care of the household expenses as long as he stayed focused on the new novel. And so he did: he ignored reality and wrote – possessed by the characters that had been whispering their stories into his ears ever since he was a small child – for a solid eight months.

Alamy

AlamyWhat came after has been recounted ad nauseam. The saga of Macondo and the Buendía family immediately became a modern classic, often compared to the works of Cervantes and Shakespeare. “It’s the book that redefined not just Latin American literature but literature, period,” said Ilan Stavans, the pre-eminent scholar of Latino culture in the United States, who claims to have read the book 30 times. García Márquez was neither a historian nor a sociologist. He was a natural storyteller. I often saw him as a prism. He was able to converge an extraordinary amount of information and transform it into a new mythology. That is the craft of One Hundred Years of Solitude: he pulled from different sources to create an alternate, hyperbolic birth of Latin American culture. And by doing so, he reinterpreted its nature.

Fact and fiction

It would be impossible to list all the sources that configured that new universe. He took a large part from the legends he heard during his childhood in Aracataca, the small Colombian town where he was born. These are the basis of the Caribbean oral traditions that lie beneath the novel’s skin. Then, he read William Faulkner as well as Greek and pre-Hispanic myths. And, finally, he took inspiration from Colombia’s violent history from the 18th to 20th Centuries. All these stories came together and ripened in his extraordinary mind, only to emerge as a different body, built using a symbolism of its own.

Alamy

AlamyGabo – as his friends and family called him – also possessed the ability to tell these stories like no one had done before him. He borrowed the pace and rhythm from Vallenato, a traditional folk music from the city of Valledupar, which he combined with the tools of narrative journalism. García Márquez was also a fantastic reporter, and such skills are showcased in his prose. I had the opportunity to see him work when I started my career at the magazine Cambioin the late ’90s. As a young journalist in Colombia, I witnessed his supernatural ability to transform the trivialities of everyday life into magical tales.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is a powerful allegory of the Latin American identity. The story, set in a time period of a century, explores many of the predominant issues in the region’s troubled history: caudillismo (the leadership of a ‘strongman’), machismo, rebellion, power, plagues, and political violence. But despite its dense social fabric, García Márquez unveils it with humour and in a refined, poetic language. And behind this somewhat conflicted social fresco, he was capable of seeing the beauty that lies in all of it. As he said in his Nobel Prize lecture: “In spite of this, to oppression, plundering and abandonment, we respond with life. Neither floods nor plagues, famines nor cataclysms, nor even the eternal wars of century upon century, have been able to subdue the persistent advantage of life over death.”

This portrait may seem like a caricature, but magical realism is built on exaggeration. The world García Marquez created is a magnifying mirror in which Latin America is able to see its flaws and its virtues. As he said in an interview with The New York Times in 1988: “I think my books have had political impact in Latin America because they help to create a Latin American identity; they help Latin Americans to become more aware of their culture.” And in this awareness lies its power.

Felipe Restrepo Pombo is a Colombian journalist, writer, and editor. In 2017, he was included in the Bogotá39 list of the best Latin American writers under 40 organised by the Hay Festival every decade. He is the author of three non-fiction books and the novel The Art of Vanishing (Seix Barral, 2016).

BBC Culture’s Stories that shaped the world series looks at epic poems, plays and novels from around the globe that have influenced history and changed mindsets. A poll of writers and critics, 100 Stories that Shaped the World, will be discussed at the Hay Festival in June and later broadcast on BBC World News.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.