How a rogue squad of designers invented ideal modern living

Weissenhofsiedlung Museum

Weissenhofsiedlung MuseumNow in its 90th anniversary year, the radical Die Wohnung project provoked outcry, iration, and changed how we live, says Dominic Lutyens.

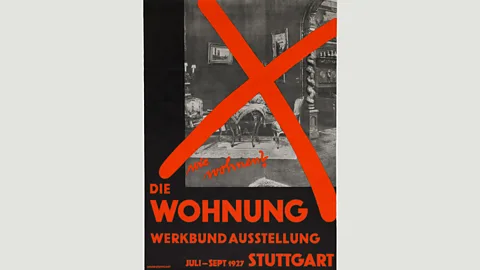

A mixture of mockery, bemusement and iration was the response when, in 1927, an architecture exhibition opened in Stuttgart. It’s hardly surprising that it proved bewildering to many.

Organised by the city of Stuttgart and Deutscher Werkbund (DWB) — an association of German artists, architects, designers and industrialists — the Die Wohnung (meaning ‘The Housing’) exhibition showcased radically innovative domestic housing.

Weissenhofsiedlung Museum

Weissenhofsiedlung MuseumIts centerpiece was a real estate project called Weissenhof. Built on sloping ground to the north of the city, this comprised 21 shockingly cuboid, flat-roofed buildings, including apartments as well as terraced and detached houses. These were generously glazed, their huge windows drawing natural light into their open-plan interiors.

The dwellings were designed by 17 European modernist architects, including Le Corbusier, his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who masterminded the project as artistic director. Although famous now, these revolutionary architects were almost unknown then.

As a single condition, van der Rohe decreed that all references to past styles were verboten in this exhibition, which celebrates its 90th anniversary this year. There was a strongly didactic thrust to the show, which preached zero tolerance for ornament, regarded as superfluous and indulgent by DWB. “It was a manifesto of the modern architecture movement,” says Anja Krämer, director of the Weissenhof Museum in Stuttgart, formerly two apartment blocks created by Le Corbusier and Jeanneret for the exhibition.

Will Baumeister/Stuttgart Archive

Will Baumeister/Stuttgart Archive“Originally two factions of architects vied to showcase their work. One group were architects with a deep connection to the region’s architectural history. But the modernists, led by Mies van der Rohe, won the battle and persuaded the city to help finance the show.”

Stuttgart’s population had never been exposed to such startlingly modern design – on such a large scale - before. Though, In 1924, the city had played host to the DWB exhibition Forme ohne Ornament (Form without Ornament), which displayed both handcrafted and industrially manufactured design, Die Wohnung was much larger. And, in thrall to the so-called machine age, its exhibitors wholeheartedly embraced mass-production and prefabrication.

The houses showcased interior design and furniture, while nearby a construction site put the spotlight on the materials and machinery needed to create the architecture. In the city centre, another arm of the exhibition displayed pared-down products that reflected the project leader’s zero tolerance for decoration or historical styles. In addition, a show called International Plan and Model Exhibition of New Architecture highlighted other cutting-edge items - photos, drawings or models – that van der Rohe and his collaborators considered important, and which lent credence to Die Wohnung’s audacious designs.

Alamy

AlamyThe artistic director had only invited avant-garde architects to take part. The team sheet included Austria’s Josef Frank, Belgium’s Victor Bourgeois, ’s Hans Scharoun, Peter Behrens and Bruno Taut, Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret (cousin of Le Corbusier) and Johannes Jacobus Pieter Oud and Mart Stam from the Netherlands.

Van der Rohe also oversaw the budgets and construction. “He told the architects how much money was in the pot for each project, then gave them free rein,” says Krämer. “He didn’t want to lay down rules as he believed this would conflict with his aim of finding new forms.”

In the event, these included moveable partitions that could allow a space to be subdivided easily and flexibly into two or three rooms, floor-to-ceiling internal glass walls and linoleum flooring in one continuous colour. The furniture was equally avant-garde — van der Rohe’s classic Weissenhof chair with a tubular-steel, cantilevered frame was created especially for the show.

Radical chic

Die Wohnung wasn’t limited to aesthetic experimentation, however. “The show was also concerned with progressive social ideas,” says Friedemann Gschwind, a Stuttgart-based architect and town-planner who initiated the creation of the museum. “For example, it showed flats for single, professional women.” Despite the arguably elitist nature of its architects’ sensibilities, Die Wohnung extended many of the democratic ideas that lay at the heart of DWB.

Weissenhofsiedlung Museum

Weissenhofsiedlung Museum“One goal was to build mass housing cheaply for those who couldn’t afford expensive homes,” says Krämer. “Another was to demonstrate that, thanks to prefabrication and modern materials, housing could be built quickly. Construction of the first house started in January, 1927 and took five-and-a-half months to complete.”

Some of the exhibition’s design concepts, such as maximising daylight with large windows and orientating buildings towards the sun — ideas now generally accepted — were partly determined by fashionable medical theories, according to Karin Kirsch, author of the book Weissenhofsiedlung, which focuses on the experimental housing built for the DWB in 1927.

“Light and air were supposed to penetrate the transparent facades, shining into the furthest corners and killing germs,” she describes. “Behrens, for one, designed apartments with balconies or roof terraces where people who were ill could take the fresh air while tucked into bed. If, in the 19th Century, an attempt was made to imitate aristocratic living, now heavy curtains and dried bouquets were seen not just as irrelevant but as dust-traps and breeding grounds for germs.”

Stuttgart Archive

Stuttgart ArchiveThe show was widely covered by the international press. “Depending on the critics’ sympathies, the reports were negative or positive,” says Krämer. “Many locals were irritated, bemused or simply laughed at what they saw. But local artists with a more modern outlook were in favour of the exhibition.”

After it had finished, the houses were to be rented out by the city of Stuttgart, which owned them, and tested in real living conditions. In 1928, many were displayed as drawings or models in a travelling exhibition, which, by 1930, had toured 14 European cities. Its influence was extensive. Architecture students in Gothenburg, Sweden, who had seen it, even boycotted all lectures based on traditional principles.

But the scheme fell foul of the Nazis who, in 1933, pronounced it a blot on Stuttgart’s landscape. “They dismissed it as a Semitic or Bolshevik suburb,” explains Krämer. “A photo collage used as Nazi propaganda depicted it [full of] Arabs, camels and monkeys to suggest it was unsuitable in . Yet, during the War, Nazis rented the houses and loved their roof terraces.”

Stuttgart Archive

Stuttgart ArchiveIn 1939, the city of Stuttgart sold the estate to the Third Reich, and in 1944 it was partly destroyed by Allied bombings. It was then badly neglected in the postwar era, and today only 11 buildings remain.

Yet, for many of the architects involved, the exhibition proved a launchpad for their careers and a life-saver: “It gained them a reputation in the US, so when they went there to escape Nazi persecution they were welcomed with open arms,” says Kirsch.

Today Die Wohnung’s importance has been recognised by Unesco, which has awarded the museum, as well as Taut’s Berlin housing estate, Hufeisensiedlung, built from 1925 to 1933, World Heritage status.

Entrance to the Weissenhof museum is free and it offers free guided tours. An exhibition of the work of Werner Graeff, Die Wohnung’s chief press officer and a modernist artist, will be held at the museum from 13 October to 17 December.

To comment on and see more stories from BBC Designed, you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. You can also see more stories from BBC Culture on Facebook and Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.