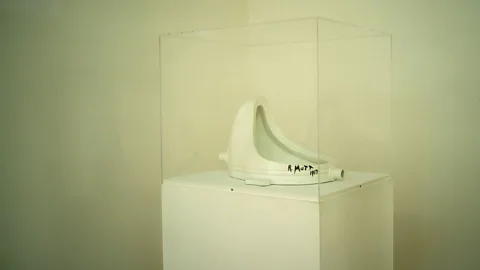

The urinal that changed how we think

Alamy

AlamyOne hundred years ago this month, Marcel Duchamp’s controversial Fountain made its debut. It would change art forever, writes Kelly Grovier.

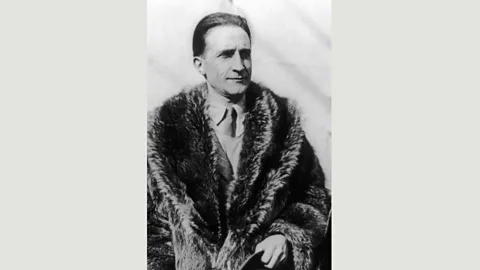

In April 1917, everything changed. At least, that is, in the world of art. It was then that the legendary avant-garde French artist and cultural prankster, Marcel Duchamp, conceived a work so controversial in its making and meaning that it would alter forever the way the game of art is played. The work in question was a porcelain urinal that Duchamp quizzically flipped onto its back, signed with a mysterious nom de plume, and called Fountain. Like a genius move by a stealthy chess master, the introduction of Fountain into the history of image-making had the effect of check-mating the art world’s sensibilities, marking the end of one kind of game and the start of another.

Alamy

AlamyThe analogy to chess is more than merely fanciful. Insisting that it “has all the beauty of art and much more”, Duchamp was obsessed with the game. (So obsessed in fact he forfeited significant pieces of his personal and creative life to its pursuit. In November 1927, after having, years earlier, shifted his energies entirely from making art to playing chess, his new wife Lydie had had enough of his incessant strategizing of moves and countermoves. One night, while he was sleeping, she glued the pieces of his set to the board. They divorced a month later.) Duchamp’s mischievous creation of Fountain 100 years ago this month is deeply in accord with the artist’s lifelong inclination towards cerebral playfulness and demonstrates the same skilful sleights of hand that a grandmaster displays when wiping the board clean with his opponents.

Alamy

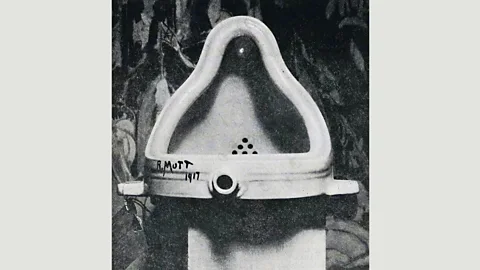

AlamyTo understand how Duchamp managed to outmanoeuvre the art world, one needs to return to the moment that the scurrilous sculpture arrived for consideration at the recently formed Society of Independent Artists in New York in spring 1917, in advance of an exhibition due to open on 10 April. As a founding member of the association, Duchamp had helped devise and articulate the organisation’s avant-garde ideology, including its commitment never to reject a work submitted by one of its . To test the sincerity and sturdiness of those principles, Duchamp entered the urinal under an assumed artistic identity - ‘R Mutt’ - knowing full well that the provocative piece would leave his fellow players in the society scrambling for their next move.

Duchamp then watched with disappointment, if not surprise, when the question of whether to exhibit the piece was put to a vote, in hypocritical violation, he believed, of the society’s widely-publicised open-mindedness. When Fountain was rejected by fellow on grounds of aesthetic crudity, Duchamp found his conscience suddenly cornered. Left with no other possible move, he resigned.

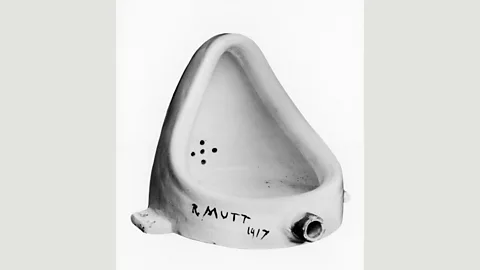

Doing so, however, left him with an awkward challenge: how, physically, to retrieve the scandalous sculpture without exposing himself as its impish author? Yet somehow Duchamp succeeded in smuggling the work out of the society undetected, aided no doubt by the reliable prejudice of anyone who might have observed him, never believing that the cumbersome hunk of porcelain plumbing was an object worth protecting. Once back in Duchamp’s possession, Fountain was whisked away to pose for Duchamp’s friend, the legendary photographer Alfred Stieglitz, whose iconic black-and-white portrait of the piece quickly etched itself into cultural consciousness.

Alfred Stieglitz/Wikipedia

Alfred Stieglitz/WikipediaDuchamp’s reluctance to sign his own name to the work, his refusal to claim credit for it, and his strenuous efforts to avoid being seen removing the work, demonstrate a remarkable resolve to distance the maker from the made. Such arduous anonymity is instructive in helping us establish principles for appreciating one of the most controversial works of art in the past century.

The age of outrage

When it comes to contemplating Fountain, observers must rethink how an aesthetic object should be approached and put aside conventional biases about the nature of artistic craftsmanship. For the first time, the significance of a work of art has been detached utterly from the artist's role in making it. After all, Duchamp did not forge the sculpture from clay with his own hands. Its significance instead lies in the object’s ability surreptitiously to skirt the scrutiny and prejudices of the eye and to engage the mind instead in a match of philosophical wits. Sliding from eye to ‘I’, Fountain gushes with conundra about the very nature of creation and what it really means to be a maker.

Alamy

AlamySince 1913, Duchamp had been experimenting with notions of originality, challenging the art world to accept as legitimate what he called ‘readymades’, or everyday commercial objects that he deemed, by situating them in a new cultural context, to be works of art. In the case of Fountain, Duchamp purchased from the JL Mott Iron Works Company in New York a new urinal which he endeavoured to estrange from its accepted identity, just as earlier he had forced observers of his painting Nude Descending a Staircase No 2 (1912), to recalibrate the way they perceive the muscular syncopations of the female form as it flexes through space.

The assumed name he attached to the object - ‘R Mutt’ - was intended, he later confessed, to being a fusion of the manufacturer’s name for the ceramic apparatus and a ‘funny’ character from the famous cartoon strip Mutt and Jeff. Writing at the time of Fountain’s rejection from The Society of Independent Artists’ exhibition, an anonymous contributor to the Dada periodical Blind Man defended the sculpture, which had come under sustained attack, in that would help propel the work and the dilemmas it posed permanently into popular imagination:

"Mr Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers’ shop windows.

"Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object."

With a flick of his wrist, Duchamp had flushed traditional notions of artistic identity down the drain. The implications for how an artist perceived his or her role in making objects would be irreversible and far-reaching.

Alamy

AlamyRemove Fountain from the cluttered chessboard of modern art, and one would need to remove too a vast army of subsequent works by artists who followed Duchamp’s fearless lead. Pop Art’s insistence on smudging the distinction between objects of high culture and the commodities of ordinary retail life directly descends from Duchamp’s notion of the readymade. No Fountain, no Warhol Brillo Boxes. No Campbell’s Soup Cans. Seminally sensational, Duchamp’s Fountain became the yardstick against which outrageousness, as an aesthetic quality, would subsequently be measured. The imagined repository for bodily waste, Fountain’s potential as a receptacle for shock is arguably filled and fulfilled 70 years later by the US artist Andres Serrano’s salacious photo of a crucifix submerged sacrilegiously in urine – a work that sparked a furore in 1987.

Alamy

AlamyTo my eye, the open-mouth gape of Fountain’s frozen yawn prefigures, too, the guffaws of Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde shark (The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991) as well as his chuckling diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007) – all three of which chortle with menacing self-confidence in their own mesmeric power. Yes, Fountain changed the game of art forever. Every so-called ‘found object’ that one encounters in a contemporary art exhibition, every infuriating row of bricks we trip over in a gallery, or dishevelled bed that makes us question the relationship between concept and execution, craft and craftiness, owes its origin to Duchamp’s audacity. With the ‘I’ of the artist now regarded as a piece that can be sacrificed without forfeiting the game, those who contemplate art have been forced to reconsider their aesthetic strategies and to practise entirely new ways of seeing.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.