The erotic masterpiece we nearly lost

Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Luis A Ferré Foundation, Inc

Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Luis A Ferré Foundation, IncFrederic Leighton’s Flaming June is now considered a treasure of Victorian painting. But at one point it was practically worthless – and nearly vanished, writes Alastair Sooke.

This is how the story goes: one day in 1962, an Irish builder walked into a junk shop on Battersea Rise in south London, carrying a painting in an elaborate gilt frame. He said that he’d found it behind a above a chimneypiece while demolishing a vacant house nearby. Hoping to flog it for a few quid, he haggled with the shop’s owner, before agreeing a price of £60. Unbeknownst to him, the picture was Flaming June (1895), by the eminent Victorian artist Frederic Leighton.

“It’s probably a cock-and-bull story,” says Daniel Robbins, senior curator of the Leighton House Museum in west London, referring to this dramatic tale of the picture’s rediscovery. (Art historians remain uncertain about its whereabouts between 1930 and 1962.) “But it has attached itself to the myth of the painting.”

Museo de Arte de Ponce

Museo de Arte de PonceLike all good stories, though, it contains an element of truth: by the 1960s, following the onslaught of Modernism, Victorian art was at a pitifully low ebb. So low, indeed, that even a ravishing masterpiece such as Flaming June – which depicts a sexy young girl in a blazing, semi-transparent saffron robe, sleeping on a marble bench beside a sparkling sea – could go unrecognised.

Having added Flaming June to his stock, the shop owner struggled to shift it: supposedly, he found it easier to sell its eye-catching ‘tabernacle’ frame, without the painting – in other words, the frame, at that moment, was valued more highly than the picture itself.

Oquendo/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Oquendo/Flickr/CC BY 2.0Not long afterwards, though, Jeremy Maas, a far-sighted art dealer with an interest in Victorian painting, acquired it. He offered Flaming June to various British galleries, including the Tate, but they all turned it down. Eventually, in the summer of 1963, Maas sold it for £2,000 to a wealthy industrialist called Luis A Ferré, who had founded a new museum in Puerto Rico. Flaming June’s sensuous evocation of a seaside idyll felt appropriate for the Caribbean, and ever since the painting has been one of the showstoppers of the Museo de Arte de Ponce, in a city on the island’s south coast.

Eternal flame

Today, of course, Flaming June belongs to a select group of pictures that are recognised and adored by the public at large. People who have never heard of Leighton are familiar with Flaming June. Over the past half century, it has been endlessly reproduced, on everything from posters and album covers to mugs, fridge magnets and jigsaw puzzles.

Alamy

AlamyAlready by the ‘70s, it was generating more money annually from fees for reproduction rights than the cost of the painting itself back in 1963. And it remains a touchstone for popular culture: in 2013, for instance, the cover of Vogue magazine presented the redheaded American actress Jessica Chastain posing in the manner of Leighton’s masterpiece. Flaming June has become a celebrity in its own right.

Yet, according to Robbins, it now “floats free” of its original context, which is why he wanted to mount Flaming June: The Making of an Icon, a new exhibition at Leighton House. For only the second time in its history (the painting was also displayed at Leighton’s studio-house in 1930, to mark the centenary of his birth), Flaming June has ‘come home’. It was here that the artist painted it, before displaying it, briefly, to a curious public.

A photograph taken on 1 April 1895 shows Flaming June, in its distinctive frame, resting on an easel inside Leighton’s sumptuously decorated studio on the first floor of his ‘private palace of art’ in Holland Park, where he lived alone. Alongside it are five other paintings that he also planned to submit to the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy, of which he had been president since 1878.

Historic England Archive. Image Courtesy of Leighton House Museum

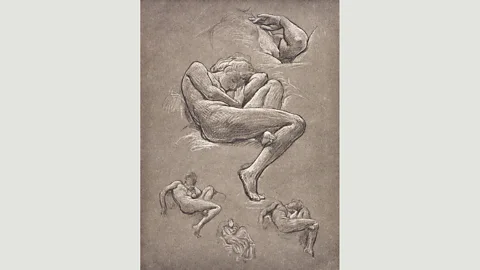

Historic England Archive. Image Courtesy of Leighton House MuseumWhat, then, do we glean from considering Flaming June in this context? Well, for one thing, we discover a great deal about how it came into being. A series of beautiful white and black chalk drawings on brown paper reveal that the idea for the painting struck Leighton when he saw a weary model resting while coiled up in an armchair, with one foot tucked behind her knee, probably at the end of a long session in the studio. He then worked on this motif – first sketching the model nude, before moving on to studies that added flickering drapery around her like a force-field.

Leighton House Museum

Leighton House MuseumMoreover, the contortion of the final composition – in particular the slumbering girl’s peculiarly elongated and prominent thigh – also owes something to Michelangelo’s Night, one of four figures that he sculpted for the Medici tombs in the church of San Lorenzo in Florence. Leighton so ired it that he kept a reproduction in his studio, beneath the large north window.

Above all, though, the exhibition at Leighton House reveals that the painting was atypical in of both Leighton’s output and Victorian painting more generally. The artist painted the pictures currently on display at Leighton House over the autumn and winter of 1894-95, soon after suffering the first of the angina attacks that would eventually kill him at the start of 1896. Each one represents a single female figure. But Flaming June is the only one to deploy colour in such an intense, even incendiary way, like a chromatic fireball.

Leighton’s ‘wife’

When it was first exhibited, critics rhapsodised about its various shades of orange (“topaz yellow” and “apricot gold” were two of the more colourful descriptions). These give the composition its fantastical, dreamlike quality. Unlike a lot of Victorian painting, which relies on narrative and recreates specific moments from history, Flaming June feels timeless, despite its vaguely ancient Mediterranean setting.

Private Collection. Image Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Private Collection. Image Courtesy of Sotheby’sThe intensity of its colour seems to signify not something out there, in the world around us, but something within: the internal dreamscape of the girl, perhaps, or the artist’s acute emotional response to his subject.

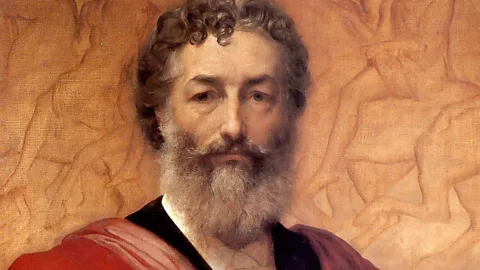

ittedly, this notion runs counter to traditional perceptions of Leighton, who was notoriously private. Yet the model for Flaming June was most likely the actress Dorothy Dene, whom Leighton met in 1879, when she was just 19 years old.

Private Collection. Image courtesy of Gallery 19C

Private Collection. Image courtesy of Gallery 19CThe pair became so close – some people even referred to Dene, cattily, as Leighton’s ‘wife’ – that the artist left her the substantial sum of £5,000 after his death. If Flaming June was unusual in of its palette, then, perhaps it was also atypical in offering a kind of revelatory autobiographical statement.

Some art historians focus on the plant that provides a splash of crimson towards the top of the composition. This is oleander, a flowering shrub. Because oleander is highly poisonous, it invites us to understand the painting’s evocation of oblivion symbolically, as a meditation on death – perhaps even Leighton’s own.

Wikipedia

WikipediaWhatever the merits of this theory, Robbins says that Leighton “hit the jackpot” with Flaming June. “I find it moving that Leighton did so right in the twilight of his career – and that he had no idea he’d done something people would forever associate with him.”

He continues: “On a superficial level, Flaming June is a seductive image of a girl asleep against the Mediterranean sun. It speaks of warmth and sensuousness. And your eye is endlessly intrigued by its form and colour.” Robbins smiles. “What’s not to like?”

Alastair Sooke is art critic of the Daily Telegraph.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.