Why La Marseillaise is the only song that matters right now

Herni Meyer / Getty

Herni Meyer / GettyThe French national anthem is the greatest anthem there is, and its history will likely only increase your iration for it, writes Alex Marshall.

It feels right now like there is only one song in the world anyone is singing: La Marseillaise, in my opinion, the greatest national anthem of them all. It has been played on radio stations in between pop songs. It has been belted out in concert halls, most notably by New York’s Metropolitan Opera this weekend. Dozens of people have been posting videos online of themselves bellowing it at full volume. And tonight, most spectacularly of all, some 70,000 football fans are going to sing it at Wembley Stadium when play England, something most English football fans could never have imagined themselves doing.

The song has in the space of a few days stopped just being ’s national anthem: it has become the ultimate symbol of solidarity, a way for everyone in the world, no matter whether they speak French or not, to express their unity with Paris following last week’s tragedy, and show they share the country’s defiance.

But one of the most remarkable things about everyone singing the Marseillaise, though, is that without realising it, every singer has tuned into the song’s very original meaning.

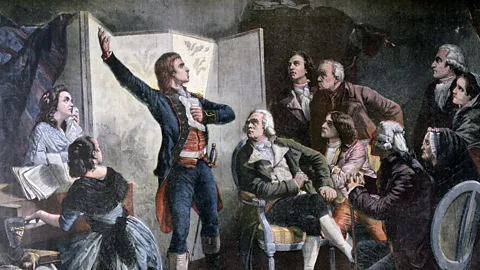

La Marseillaise was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, a 31-year-old soldier and amateur violinist. He was in Strasbourg on the night of 25 April fearing Austria was about to invade, intent on rolling back the French Revolution and restoring Louis XVI to full power. The city’s mayor was desperate for something to inspire the city as it faced devastation and that night begged Rouget de Lisle to have a go at writing something – anything – that might help.

Rouget de Lisle ran back to his room half-drunk from that meeting and in the space of just a few hours wrote la Marseillaise. He probably stole the music from a popular song of the day, and he definitely stole half the words from graffiti plastered around the city – but what he created that night was undeniable, a song of defiance that would give everyone who heard it hope.

Yes, he did make it incredibly bloodthirsty. One line says, “Can you hear them in the countryside coming to slit the throats of your wives and children?” While the chorus cries out, “To arms, citizens… let’s water the fields with impure blood.” But Rouget de Lisle realised he needed to make it so shocking to motivate. He also knew those were not the song’s key lines. That goes to this the opening of the first verse. “Arise children of the fatherland, against us tyranny’s blood banner is raised,” it says. It is those lines that seem to be resonating around the world at this moment.

If you do not think the Marseillaise is great musically, you should only need to look at how the song has been used by other musicians to change your mind. Everyone from Wagner to The Beatles, Debussy to Serge Gainsbourg has taken it for their own. Perhaps most famously, it was used by Tchaikovsky in his great 1812 Overture. He meant it to symbolise about to be defeated by Russian troops, but it is such a powerful melody, anyone listening would think is the real winner in that battle.

It is a song that has inspired French people throughout the country’s history. A French general once said it was worth 1,000 extra men in battle. A German poet once wrote that it was responsible for the death of 50,000 of his countrymen. In both the first and second world wars it was sung continually in in an effort to inspire (even though the Vichy Government banned it). The famous scene in Casablanca of a French crowd tearfully and resolutely singing it to drown out some celebrating Nazi soldiers does not in the slightest overplay the emotion the song can invoke.

Tonight’s singing at Wembley is likely to be just as emotional and powerful as any past rendition. Get ready to in.